Have scientists greatly misunderstood what a planet is, and has Pluto, formerly the 9th planet in the solar system, been wrongfully revoked of its planetary status? According to one recent academic study, that may very well have been the case.

Indeed, this study, published in the academic journal Icarus, posits that our entire traditional understanding of what constitutes a planet may be wrong - a theory that has significant implications.

Why was Pluto downgraded?

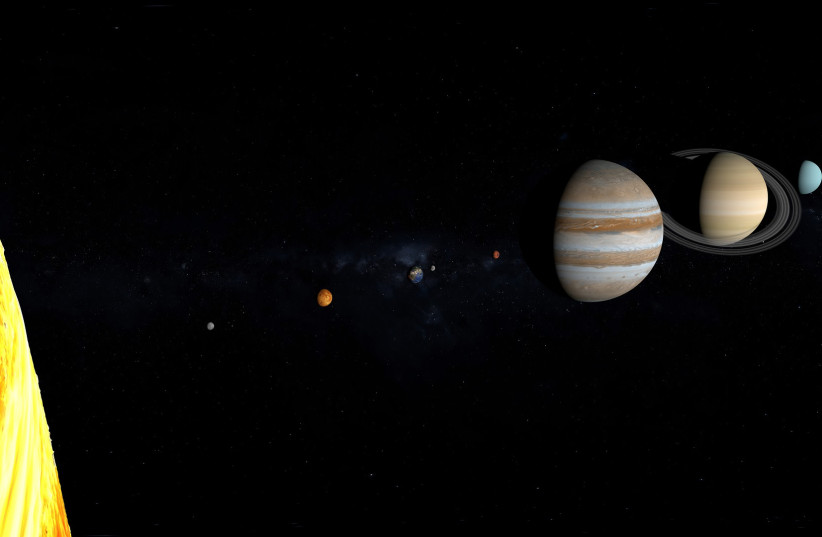

Until 2006, it was commonly accepted that the solar system had nine planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto. However, in 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU), which classifies the various objects in our solar system, made a ruling that shook the astronomy world: Pluto was no longer a planet, but instead a dwarf planet, bringing our total number of planets in the solar system down to eight.

The reason for this was, ostensibly, because Pluto failed to meet one of the three criteria needed to be considered a planet. It was spherical and orbited the sun, but its orbit wasn't cleared of other objects and it was influenced by Neptune's gravity.

But according to this new study, the reason to remove Pluto's planet status wasn't based on scientific understanding of what is a planet, but is rather based on astrology.

This paper was, essentially, the culmination of a careful five-year study of the academic literature of astronomy and planetary sciences going back four centuries to figure out just what is a planet.

According to Galileo, the definition of a planet was simple: An object in space that is geologically active.

And indeed, according to the literature, that definition held firm from the 1600s until the early 20th century. Here, two things came into play: a decline in planetary science articles in academia and the popularity of almanacs, books that were rooted in astrology.

And this could have caused astrology to worm its way into planetary classification.

“We found that there were enough almanacs being sold in England and in the United States that every household could get one copy every year,” lead author Philip Metzger, PhD of the University of Central Florida's Florida Space Institute said in a statement.

“This might seem like a small change, but it undermined the central idea about planets that had been passed down from Galileo,” he explained. “Planets were no longer defined by virtue of being complex, with active geology and the potential for life and civilization. Instead, they were defined by virtue of being simple, following certain idealized paths around the Sun.”

This began to change in the 1960s when interest in planetary science was renewed. But in 2006, the IAU ruled Pluto was not a planet and did this by creating a third requirement, of having a clear orbit, which seemingly had seldom been used in planetary science before.

Why does Pluto's status matter?

According to Metzger, the idea was to intentionally keep the number of planets in the solar system small. This was not just because of Pluto though, but because of other objects. A few other objects had been known in the solar system by 2006, when this decision was made. These include the dwarf planets Makemake and Eris.

Metzger believes the decision was meant to exclude them as well as Pluto.

This usage of astrology to limit the number of planets and inclusion of never-before-used criteria has, as Metzger puts it, led most scientists to ignore the IAU, NBC reported.

So why does this debate over planetary classification in our solar system and the status of Pluto matter?

For several reasons. One of these is that using this astrology-based classification system is harmful to the study of planetary science as it leaves what should be considered planets disregarded.

But one of the biggest reasons is that planetary science is rapidly expanding and the possibilities for further study are increasing.

This is especially true with growing interest in the study of exoplanets - planets outside the solar system - and the recent launch of NASA's new James Webb Space Telescope, the most advanced space telescope ever launched, which will be able to change how scientists study the many objects and phenomenon populating the universe - including planets.

In fact, it also brings greater attention to our own solar system as well, because it isn't just Pluto that has been misclassified under the Galileo definition.

Other objects traditionally considered moons like Titan, Triton and more would, under this definition, be considered a planet because they are geologically active.

But this begs the question: If our understanding of planets is wrong, and other objects in the solar system could qualify as planets under the Galileo definition, then how many planets does the solar system really have? According to Metzger: Probably around 150.

This definition, if accepted back into the mainstream properly, could help expand our understanding of planetary science and see that our solar system may be a lot more crowded than we first thought.