Hardly anyone except for children in lower grades know how to write with a pen or pencil; keyboards and smartphone screens have almost completely taken over. And cursive writing in English is hardly taught in Israeli schools anymore. But is this good for the brain?

In fact, the pen is mightier than the (key)board. New research just published by researchers the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and published in Frontiers in Psychology has shown that writing by hand leads to higher brain connectivity than typing on a keyboard.

Prof. Audrey van der Meer, a brain researcher at the university in Trondheim whose study appeared under the title “Handwriting but not Typewriting Leads to Widespread Brain Connectivity: A High-Density EEG Study with Implications for the Classroom,” highlighted the need to expose pupils and students to more handwriting activities.

“When writing by hand, brain connectivity patterns were far more elaborate than when typewriting on a keyboard, as shown by widespread theta/alpha connectivity coherence patterns between network hubs and nodes in parietal and central brain regions. Existing literature indicates that connectivity patterns in these brain areas and at such frequencies are crucial for memory formation and for encoding new information and, therefore, are beneficial for learning,” she asserted.

“As digital devices progressively replace pen and paper, taking notes by hand is becoming increasingly uncommon in schools and universities. Using a keyboard is recommended because it’s often faster than writing by hand. However, writing with a pen has been found to improve spelling accuracy and memory recall,” she added.

Study suggests that students should take notes in class by hand, not on laptop

Participants were mostly students and were recruited at the university campus. They received a $15 cinema ticket for taking part. To avoid crossover effects between the two hemispheres, only right-handed participants were included.

To find out if the process of forming letters by hand resulted in greater brain connectivity, researchers in Norway now investigated the underlying neural networks involved in both modes of writing. We show that when writing by hand, brain connectivity patterns are far more elaborate than when typewriting on a keyboard,” she added. “Such widespread brain connectivity is known to be crucial for memory formation and for encoding new information and, therefore, is beneficial for learning.”

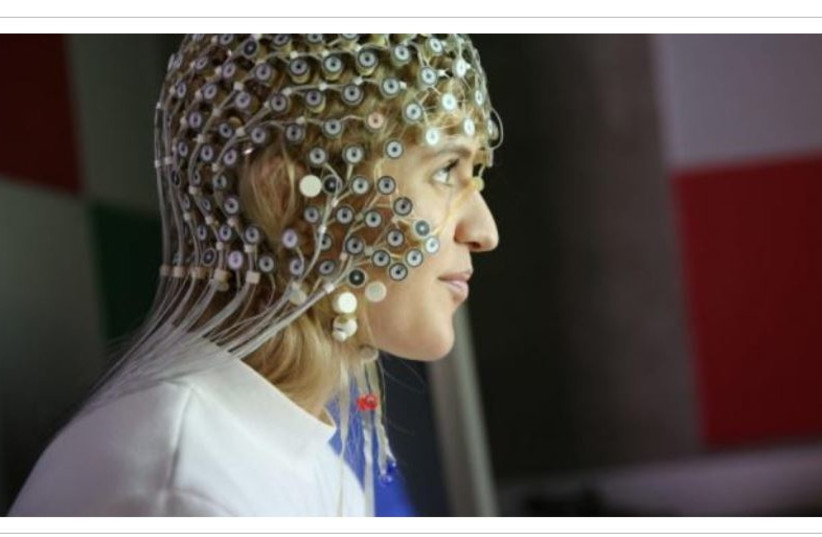

The researchers collected electroencephalogram (EEG) data from 36 university students who were repeatedly prompted to either write or type a word that appeared on a screen. When writing, they used a digital pen to write in cursive directly on a touchscreen. When typing they used a single finger to press keys on a keyboard. High-density EEGs, which measure electrical activity in the brain using 256 small sensors sewn in a net and worn on the head, were recorded for five seconds for every prompt.

Connectivity of different brain regions increased when participants wrote by hand, but not when they typed. “Our findings suggest that visual and movement information obtained through precisely controlled hand movements when using a pen contribute extensively to the brain’s connectivity patterns that promote learning,” van der Meer said.

Although the participants used digital pens for handwriting, the researchers said that the results are expected to be the same when using a real pen on paper. “We have shown that the differences in brain activity are related to the careful forming of the letters when writing by hand while making more use of the senses,” van der Meer explained. Since it is the movement of the fingers carried out when forming letters that promotes brain connectivity, writing in print is also expected to have similar benefits for learning as cursive writing.

On the contrary, the simple movement of hitting a key with the same finger repeatedly is less stimulating for the brain. “This also explains why children who have learned to write and read on a tablet can have difficulty differentiating between letters that are mirror images of each other, such as ‘b’ and ‘d’. They literally haven’t felt with their bodies what it feels like to produce those letters,” van der Meer said.

Their findings show the need to give school pupils and college/university students the opportunity to use pens, rather than having them type during class, the researchers said. Guidelines to ensure that students receive at least a minimum of handwriting instruction could be an adequate step, she suggestion. In fact, cursive writing training has been re-implemented in many US states at the beginning of the year.

At the same time, it is also important to keep up with continuously developing technological advances, she cautioned. This includes awareness of what way of writing offers more advantages under which circumstances. “There is some evidence that students learn more and remember better when taking handwritten lecture notes, while using a computer with a keyboard may be more practical when writing a long with a keyboard may be more practical when writing a long when writing a long text or essay,” van der Meer concluded.