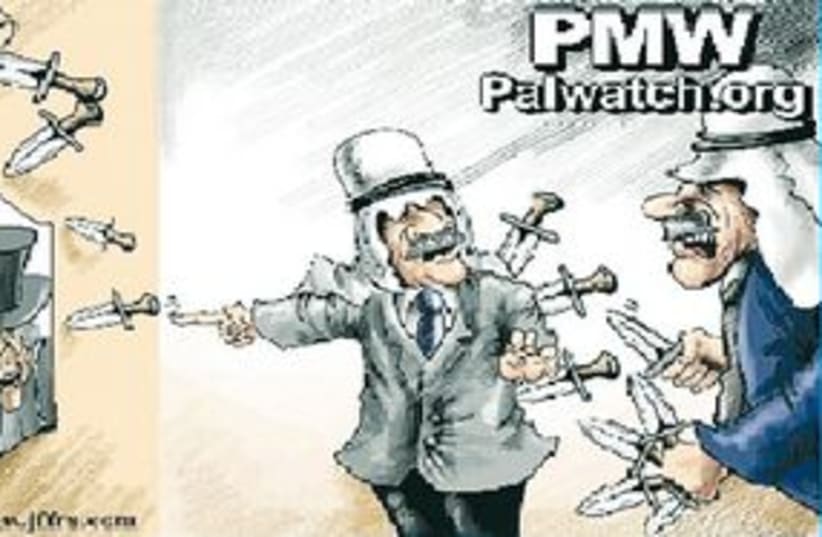

In ancient times, messages were delivered by a human envoy, sometimes sent from the enemy camp. An easily-provoked combatant might vent his anger on the deliverer of an unpopular message by killing the messenger.When I read on Sunday that after receiving complaints from users, YouTube had removed from its servers a video channel run by an Israeli NGO for repeatedly airing hate speech, I thought there hardly existed a more perfect example of “shooting the messenger.”Palestinian Media Watch did show videos of incitement that were “indeed horrific,” in the words of PMW’s Itamar Marcus, but their content was directed against Jews and Israelis and recorded from Palestinian and other Arab media.True, the disturbing videos were posted as part of an agenda: to educate the wider public about what was being disseminated among Arabs, in their own language, as opposed to what is said in English to Western audiences.Essentially, PMW took on the role of messenger, and was “shot” for it.Following outrage from supporters of the Israeli NGO and a report in this newspaper, the website reinstated the PMW channel a day later. Its staff presumably (hopefully) realized that there is a vast difference between those who purvey hate and those who work to unmask them; and that disgusting as a Hamas terrorist’s call on Palestinians to drink the blood of Jews may be – to describe just one video – PMW was simply exposing this and similar barbaric exhortations that it believed non-Arabic speakers should be aware of.The reinstatement of PMW’s channel suggests that YouTube’s operators understood, albeit belatedly: It’s wrong to shoot the messenger.IN 2002, Time magazine named as its Persons of the Year “The Whistleblowers” – Sherron Watkins, the vice president of Enron, who wrote a letter to company chairman Kenneth Lay warning him that the company’s accounting methods were improper; Coleen Rowley, the FBI attorney who caused a tornado with her memo to FBI director Robert Mueller about how the bureau had brushed off her pleas that Zacarias Moussaoui (now indicted as a 9/11 co-conspirator) be investigated; and Cynthia Cooper, who informed WorldCom’s board that the company had concealed $3.8 billion in losses.The three women weren’t after publicity. They initially tried to keep their criticism in-house, and became whistleblowers only when their memos were leaked.These “messengers” were, in the words of Richard Lacayo and Amanda Ripley, “what New York City firefighters were in 2001: heroes at the scene, anointed by circumstance… people who did right just by doing their jobs rightly… with eyes open and with the bravery the rest of us always hope we have and may never know if we do.”But Watkins, Rowley and Cooper also suffered, “because whistleblowers don’t have an easy time. Almost all say they would not do it again. If they aren’t fired, they’re cornered: isolated and made irrelevant. Eventually, many suffer from alcoholism or depression.”Though that didn’t happen to the three women, they say that “some of their colleagues hate them.” And Cooper told the interviewers: “There have been times that I could not stop crying.”You don’t have to shoot a messenger to give him or her heartache.CHRISTOPH Meili, who in early 1997 worked as a night guard at the Union Bank of Switzerland in Zurich, discovered that UBS officials were destroying documents detailing the credit balances of deceased Jewish clients whose heirs’ whereabouts were unknown.He also found in the shredding room books from the German Reichsbank listing stock accounts for companies involved in the Holocaust, and real estate records for Berlin property that had been forcibly taken by the Nazis, placed in Swiss accounts, and then claimed to be owned by UBS. Destruction of such documents violates Swiss law.Meili gave some of these bank files to a local Jewish organization, which handed them over to the police; and to the press, which published them.A brave act: But in many ways, this intrepid messenger was “shot.”A judicial investigation was opened against him for suspected violation of Swiss banking secrecy laws (it was later closed), and he received death threats. He and his family left for the US, where they were granted political asylum. In January 1998, a suit was filed on his behalf against UBS, demanding a sum of $2.56 billion. A $1.25b. settlement, which included Meili’s costs, was reached with the bank.Meili’s marriage ended in 2002, and he complained that he never received the money promised in the settlement. He became a naturalized US citizen and started working in security again, claiming that those who had once championed him had let him down, including the Jewish organization he originally approached with his precious find.He said he was working for minimum wage. He returned to Switzerland in 2009, homeless.In his book Imperfect Justice, Stuart Eizenstat suggests that the “Meili Affair” was significant in the Swiss banks’ decision to participate in reparations for Nazi victims of WW2.Does Meili’s story support some cynics’ view that “no good deed goes unpunished,” or was he himself instrumental in the downward spiral that followed his brave mission?THE world media are working overtime to report on an elusive and shady individual who considers himself a messenger and possibly hero par excellence, bursting to deliver reams of information he believes should be freely accessible. Many disagree.And many of the politicians and other senior figures who feature in the trove of secret US military and diplomatic cables that WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange began to publish last month would probably be delighted to shoot him personally.Failing that, the next best thing, in their view, is the fact that American officials are determined to prosecute Assange to the full extent of the law on charges relating to his release of the 250,000 classified cables. The 39-year-old Australian is also facing charges of rape, molestation and unlawful coercion of two women in Sweden.Are the latter charges politically motivated – as Assange’s supporters claim – cooked up to silence a troublesome and embarrassing agitator? Or is this one “messenger” who does deserve punishment for delivering his message(s)?His leaks tend to expose US secrets, but, curiously, none from Iran or China. His sources of funding are obscure, and the data he released was stolen by a traitorous or misguided soldier.Those who side with him and cheer his dissemination of the cables include Vaughan Smith, founder of London’s Frontline Club for journalists and owner of the 10-bedroom British country mansion to which Assange is currently restricted as a condition of his bail as he fights extradition to Sweden.One thing is certain: The ramifications of the WikiLeaks saga are far-reaching, as “traditional watchdog journalism, which has long accepted leaked information in dribs and drabs, has been joined by a new counterculture of information vigilantism that now promises disclosures by the terabyte,” to quote Scott Shane in The New York Times this week.IT’S unlikely we will ever find ourselves in the position of being messengers whose revelations get reported by the media. But suppose we come into possession of intimate knowledge that we feel it is wrong to hold onto.Suppose a close relative has a serious illness that is being kept secret from him or her, and you have an unshakable conviction that this is bad. Or suppose you know that your best friend’s husband is having an affair and feel compelled to tell her for her own good.Many people who have delivered such personal “messages” have lived to regret it, finding themselves not thanked, but rejected and perhaps even detested by the recipients. The once-best friend may suddenly find herself considered no friend at all.Discretion, we can discover too late, is often the better part of valor.But should one feel one’s conscience urging the delivery of a “message” one knows will not be serenely received, one must consider the implications of such a revelation from every conceivable angle. One needs to seek discreet and expert advice, if possible, and then proceed as if treading on thin ice – which is, of course, exactly what one is doing.Above all, one must examine one’s own motivation minutely and be quite sure that one is not delivering the message for the sake of any personal benefit.Some folk seem to take delight in spreading bad news. They need to be aware that they themselves may, as a result, come to be regarded as “bad news.”

In My Own Write: Messengers and their motives

One must examine one’s own motivation minutely and be quite sure that one is not delivering the message for the sake of any personal benefit.

In ancient times, messages were delivered by a human envoy, sometimes sent from the enemy camp. An easily-provoked combatant might vent his anger on the deliverer of an unpopular message by killing the messenger.When I read on Sunday that after receiving complaints from users, YouTube had removed from its servers a video channel run by an Israeli NGO for repeatedly airing hate speech, I thought there hardly existed a more perfect example of “shooting the messenger.”Palestinian Media Watch did show videos of incitement that were “indeed horrific,” in the words of PMW’s Itamar Marcus, but their content was directed against Jews and Israelis and recorded from Palestinian and other Arab media.True, the disturbing videos were posted as part of an agenda: to educate the wider public about what was being disseminated among Arabs, in their own language, as opposed to what is said in English to Western audiences.Essentially, PMW took on the role of messenger, and was “shot” for it.Following outrage from supporters of the Israeli NGO and a report in this newspaper, the website reinstated the PMW channel a day later. Its staff presumably (hopefully) realized that there is a vast difference between those who purvey hate and those who work to unmask them; and that disgusting as a Hamas terrorist’s call on Palestinians to drink the blood of Jews may be – to describe just one video – PMW was simply exposing this and similar barbaric exhortations that it believed non-Arabic speakers should be aware of.The reinstatement of PMW’s channel suggests that YouTube’s operators understood, albeit belatedly: It’s wrong to shoot the messenger.IN 2002, Time magazine named as its Persons of the Year “The Whistleblowers” – Sherron Watkins, the vice president of Enron, who wrote a letter to company chairman Kenneth Lay warning him that the company’s accounting methods were improper; Coleen Rowley, the FBI attorney who caused a tornado with her memo to FBI director Robert Mueller about how the bureau had brushed off her pleas that Zacarias Moussaoui (now indicted as a 9/11 co-conspirator) be investigated; and Cynthia Cooper, who informed WorldCom’s board that the company had concealed $3.8 billion in losses.The three women weren’t after publicity. They initially tried to keep their criticism in-house, and became whistleblowers only when their memos were leaked.These “messengers” were, in the words of Richard Lacayo and Amanda Ripley, “what New York City firefighters were in 2001: heroes at the scene, anointed by circumstance… people who did right just by doing their jobs rightly… with eyes open and with the bravery the rest of us always hope we have and may never know if we do.”But Watkins, Rowley and Cooper also suffered, “because whistleblowers don’t have an easy time. Almost all say they would not do it again. If they aren’t fired, they’re cornered: isolated and made irrelevant. Eventually, many suffer from alcoholism or depression.”Though that didn’t happen to the three women, they say that “some of their colleagues hate them.” And Cooper told the interviewers: “There have been times that I could not stop crying.”You don’t have to shoot a messenger to give him or her heartache.CHRISTOPH Meili, who in early 1997 worked as a night guard at the Union Bank of Switzerland in Zurich, discovered that UBS officials were destroying documents detailing the credit balances of deceased Jewish clients whose heirs’ whereabouts were unknown.He also found in the shredding room books from the German Reichsbank listing stock accounts for companies involved in the Holocaust, and real estate records for Berlin property that had been forcibly taken by the Nazis, placed in Swiss accounts, and then claimed to be owned by UBS. Destruction of such documents violates Swiss law.Meili gave some of these bank files to a local Jewish organization, which handed them over to the police; and to the press, which published them.A brave act: But in many ways, this intrepid messenger was “shot.”A judicial investigation was opened against him for suspected violation of Swiss banking secrecy laws (it was later closed), and he received death threats. He and his family left for the US, where they were granted political asylum. In January 1998, a suit was filed on his behalf against UBS, demanding a sum of $2.56 billion. A $1.25b. settlement, which included Meili’s costs, was reached with the bank.Meili’s marriage ended in 2002, and he complained that he never received the money promised in the settlement. He became a naturalized US citizen and started working in security again, claiming that those who had once championed him had let him down, including the Jewish organization he originally approached with his precious find.He said he was working for minimum wage. He returned to Switzerland in 2009, homeless.In his book Imperfect Justice, Stuart Eizenstat suggests that the “Meili Affair” was significant in the Swiss banks’ decision to participate in reparations for Nazi victims of WW2.Does Meili’s story support some cynics’ view that “no good deed goes unpunished,” or was he himself instrumental in the downward spiral that followed his brave mission?THE world media are working overtime to report on an elusive and shady individual who considers himself a messenger and possibly hero par excellence, bursting to deliver reams of information he believes should be freely accessible. Many disagree.And many of the politicians and other senior figures who feature in the trove of secret US military and diplomatic cables that WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange began to publish last month would probably be delighted to shoot him personally.Failing that, the next best thing, in their view, is the fact that American officials are determined to prosecute Assange to the full extent of the law on charges relating to his release of the 250,000 classified cables. The 39-year-old Australian is also facing charges of rape, molestation and unlawful coercion of two women in Sweden.Are the latter charges politically motivated – as Assange’s supporters claim – cooked up to silence a troublesome and embarrassing agitator? Or is this one “messenger” who does deserve punishment for delivering his message(s)?His leaks tend to expose US secrets, but, curiously, none from Iran or China. His sources of funding are obscure, and the data he released was stolen by a traitorous or misguided soldier.Those who side with him and cheer his dissemination of the cables include Vaughan Smith, founder of London’s Frontline Club for journalists and owner of the 10-bedroom British country mansion to which Assange is currently restricted as a condition of his bail as he fights extradition to Sweden.One thing is certain: The ramifications of the WikiLeaks saga are far-reaching, as “traditional watchdog journalism, which has long accepted leaked information in dribs and drabs, has been joined by a new counterculture of information vigilantism that now promises disclosures by the terabyte,” to quote Scott Shane in The New York Times this week.IT’S unlikely we will ever find ourselves in the position of being messengers whose revelations get reported by the media. But suppose we come into possession of intimate knowledge that we feel it is wrong to hold onto.Suppose a close relative has a serious illness that is being kept secret from him or her, and you have an unshakable conviction that this is bad. Or suppose you know that your best friend’s husband is having an affair and feel compelled to tell her for her own good.Many people who have delivered such personal “messages” have lived to regret it, finding themselves not thanked, but rejected and perhaps even detested by the recipients. The once-best friend may suddenly find herself considered no friend at all.Discretion, we can discover too late, is often the better part of valor.But should one feel one’s conscience urging the delivery of a “message” one knows will not be serenely received, one must consider the implications of such a revelation from every conceivable angle. One needs to seek discreet and expert advice, if possible, and then proceed as if treading on thin ice – which is, of course, exactly what one is doing.Above all, one must examine one’s own motivation minutely and be quite sure that one is not delivering the message for the sake of any personal benefit.Some folk seem to take delight in spreading bad news. They need to be aware that they themselves may, as a result, come to be regarded as “bad news.”