A digital Holocaust is unfolding – and social media is fueling it - opinion

Platforms that promised connection have become factories of radicalization.

Platforms that promised connection have become factories of radicalization.

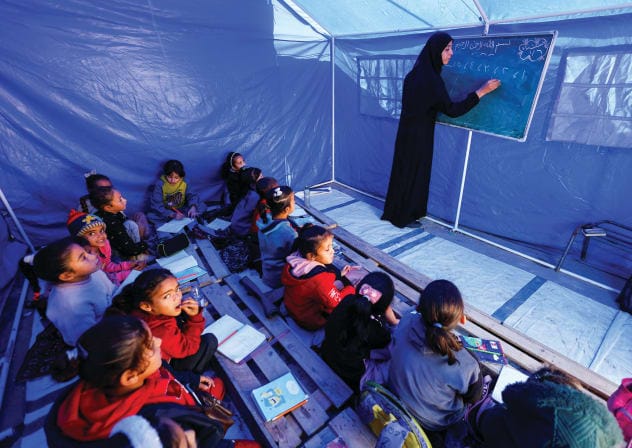

The core reform in education in Gaza has to be based on demilitarization, deradicalization, democratization, and development.

Military force and public pressure collided for 843 days, and together, they brought every hostage home.

“If it ends like this, he will be remembered as the worst president ever for Iranians,” one Iranian who managed to flee told The Jerusalem Post.

No matter how unjustly countries treat Israel and their local Jewish populations, we traveling mohalim must make the journey to ensure our most sacred tradition continues, even on the hardest days.

If Saudi Arabia thinks “Zionist” is an Insult, it’s not ready for Abraham Accords peace or economic integration.

From mass protests to empty airports, Iran’s collapsing air traffic gives insight into the mounting economic and political crisis facing the regime.

You are not building a state in Somalia – you are funding a syndicate that mocks you and fuels the war against your allies.

Zionism without goals is not a mistake—it is a moral abdication, and we are standing inside it.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s latest attack on former president Joe Biden is not merely another sign of ingratitude or habitual deflection, but is designed to resonate with Donald Trump.

President Trump’s Iran policy feels confusing, and that’s the point, to create strategic instability.