In My Own Write: Getting away from it all, sort of

Over there we didn’t feel the need to glance over our shoulders to see who was coming up behind, as we presently tend to do in Jerusalem.

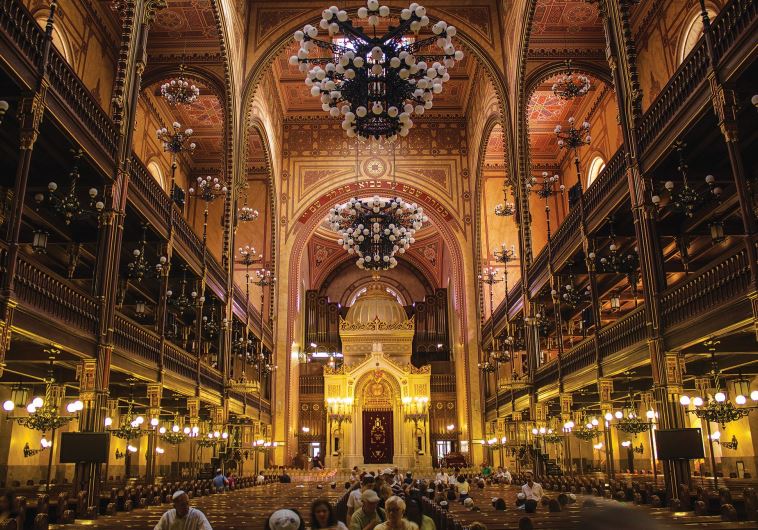

Dohány Street Synagogue, Budapest(photo credit: LENNART TANGE/FLICKR)Updated:

Dohány Street Synagogue, Budapest(photo credit: LENNART TANGE/FLICKR)Updated: