With a few months of hindsight, we can take a look at what then seemed like a swelling wave in aliyah from Ukraine. It is more appropriate than ever to consider making aliyah.

There are many situations that comprise scenarios for aliyah. Immigration was set as a foundational raison d’etre for the State of Israel and was enacted into law in 1950: “... the renewal of the Jewish state in the Land of Israel, which would open wide the gates of the homeland to every Jew...”

Russian President Vladimir Putin, as of two weeks into his aggressive war against Ukraine, stood out as somewhat of an anomaly in Russian history. As former Jewish Agency director Natan Sharansky recently said in Tablet magazine, “The fact [is] that even Putin, with all the awful things he is doing, is unique in Russian history for his positive attitude toward Jews and Israel. There are no anti-Jewish pogroms at this stage, neither in Ukraine nor in Russia, and it’s not the case that Jews are at the center of this.”

“The fact [is] that even Putin, with all the awful things he is doing, is unique in Russian history for his positive attitude toward Jews and Israel. There are no anti-Jewish pogroms at this stage, neither in Ukraine nor in Russia, and it’s not the case that Jews are at the center of this.”

Natan Sharansky

Putin has earned a reputation as the Russian leader who has not demonstrated antisemitism as a motivation in his grabby torrent of firepower on Ukraine. One might say he seems to be an equal-opportunity aggressor.

Nonetheless, the Jews of Ukraine, unique among the victims of the Russia-Ukraine war, are undergoing a “selection” of another sort. This time, unlike in the memories of those able to remember the 1930s and ’40s, being a Jew is an advantage, an ace-in-the-hole, giving people the option of a new start in Israel.

In a startling slap of reality, being a Jew is a ticket to a country that, warts and all, takes this task seriously, as it has done with every wave of newcomers since the founding of the state. This is aliyah at its essence – human life on the line and escaping under live fire – as seen on TV screens and devices in real-time.

In the months since the war began, we have also seen some aggressive acts in Russia against Jewish Agency activities. So, “antisemitic” or not, somehow there is a backlash against Israel, the home of the Jews. Analysts and politicians will have their say.

Mostly, this is not the way people usually consider moving to Israel. Thankfully, it is not normally undertaken amid the drama of artillery fire; it happens in a slower, more contemplative way.

FOR MANY, Israel, Jews and identity are a continuous preoccupation. As our country approaches a ripe old age, we can allow ourselves a turn inward. We have the luxury of our own country; we have the responsibility, too. Is Israel for everyone? Why are some Jews able to live full and meaningful lives around the globe and never consider moving here, while others live with inner turmoil until they make the move? And then?

The suicide by a young immigrant in Jerusalem a few months ago caused many to pause, shaken, for brief seconds or longer. What could have helped avoid that tragic result?

This incident affected me deeply. The following is meant as an examination of some of the issues that face young adults as they consider moving to Israel. It is not meant to provide fodder to anti-Zionists or to discourage potential olim (immigrants). It is meant to temper stars-in-the-eyes idealism with realistic expectations and, hopefully, better equip olim to have a successful transition.

It is not only the young and searching idealists who encounter snags when moving to Israel. These are factors to consider for any potential immigrant at any point in life, whether student, established professional, mid-life family moving together or retirees. Changing countries is not a simple process.

I am maybe the last person to give advice on planning aliyah. I never planned it. As a young student in my 20s, I had a hard time planning for the weekend, let alone planning for life. After more than 40 years in Israel, I can share some observations. Here is my one piece of advice: When you pack your lift, leave some space for your sense of humor.

Every person has his or her own needs, desires, abilities, talents – and the list goes on. What is right for one can be very wrong for another.

I didn’t really leave America and close the door. I love America, and being raised by immigrant refugees, I marinated in their patriotism and in their gratitude for being taken in (though too late for many other relatives).

I have never disembarked from that 12-hour flight to New York without my eyes tearing up as I enter the very wide corridors to the first JFK Airport entry hall with the Stars ‘n’ Stripes. I stand in the citizens’ line and approach the officers to hand them my US passport. I wait for the minute when they ask me why I’ve come – a formality; and as they hand my passport back, if the tired workers don’t say it, I ask them to say “Welcome home.” And they do. And it is.

And it isn’t. Unlike some, I was raised in a secular, pluralistic way, with a love of the good life, a little light on Jewish ritual, weak Jewish education, no Jewish summer camps, and far from large Jewish communities. Every Hebrew word and Jewish concept gained was a struggle; I invented efes (zero) motivation.

With Israel in the headlines throughout those formative years, despite myself, my curiosity rose. Zionism, as far as my refugee parents were concerned, was important. They were active in Jewish organizations – but aliyah? Aliyah was for other people’s children; they had already had more than enough upheaval in their war-bracketed lives.

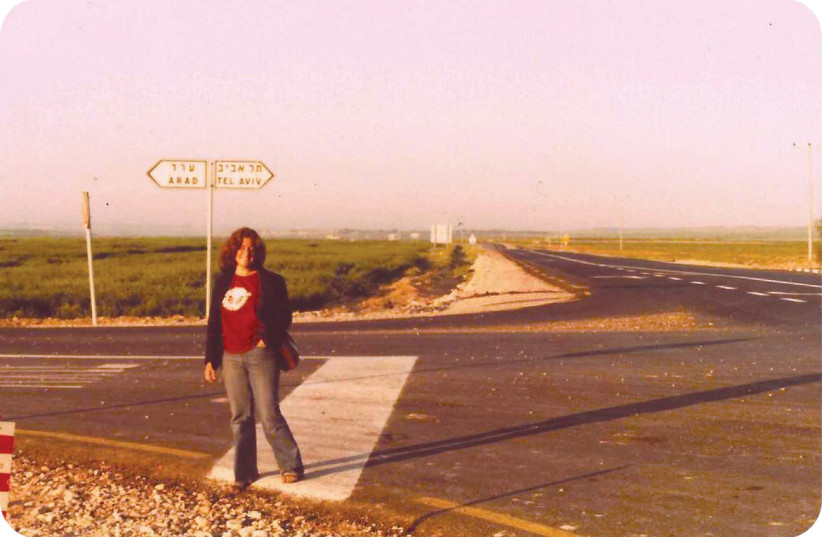

AS A TRANSITION from leaving formal education, I planned my first trip to Israel. My boyfriend, from a strongly Jewish and Zionistic family, planned his aliyah. I went to a stateside ulpan to brush up on what those letters looked like and how they formed words. I made an appointment with a shaliach (aliyah emissary) – a new word for me. I was offered a narrow range of choices, and I came to Israel for the first time to a program in Arad designed for college grads. I lived in what they called a development town.

In retrospect, it was perfect for me. Not the most dedicated Hebrew student (for which I am still paying), it also offered a range of stimulating classes that filled in some education gaps. My real education had begun. Every sensation and experience was new, forcing me to confront my identity. I stayed.

That boyfriend, now husband of many years, says that I am still on my first visit. Though I was very lucky in many ways, I would not say that it has been a smooth ride. There was nothing easy about going through a total life change.

<br>There was a lot to get used to

We didn’t have the stunning array of produce and convenience foods that are now fairly attainable (broccoli, asparagus and blueberries were for occasional US visits). We didn’t have air-conditioning on buses, we didn’t have Sundays off, or Fridays either; and we didn’t have takeaway food or deliveries. And no bagel shops for decades to come.

A memorable early meltdown was my foodie frustration of not being able to find a crucial item: a wire whisk. (I compensated since with at least three sizes in six food categories).

Calls home were infrequent and brief, and in between we wrote on flimsy single-sheet aerograms that could – with some luck – get a response in three weeks. For major life events, we got 10-word telegrams (the retro mini-tweet).

When I look at Facebook lists of what concerns new immigrants, I am amused. But I don’t snicker at the desire for familiarity. I am glad I can now take a swig of root beer. The pangs for familiar tastes and brands are real, and mostly easy enough to indulge until you realize one day that it is no longer so important. Our lack of consumer items was extensive but generally trivial. Other things loomed large, like tolerance, coexistence, mutual respect, quiet borders.

What we did have: We had a purpose. We had a sense of living in a work-in-progress. We had a sense of getting to be part of the best chance for the Jewish people in 2,000 years, and we could either have a front seat – be present – or miss it. I was too young for Woodstock; I was not going to miss out on the greatest development in the history of the Jews. I wanted in.

<br>Early adjustment

We dealt directly with every piece of bureaucracy that Israel required of us. We had to brave places like the Immigration and Absorption Ministry, Interior Ministry, health funds, driver’s licenses, banks and professional education certification, all on our own – and just like that (not) it was done.

We managed this with my husband’s day school non-conversational Hebrew and my level alef-2 Hebrew as we dealt with clerks – between inevitable coffee breaks – whose entire English vocabulary consisted of taglines from Dynasty and Starsky and Hutch reruns.

This is all by way of saying that I can feel myself standing in the shoes of a young immigrant of today. Would I have changed places and been happy to redo my aliyah of then for the convenience and ease afforded by making such a big life change through the experts of Nefesh B’Nefesh? Admittedly, just looking at their website makes me swoon in amazement. The times have a’changed.

There is no question that technology has bridged much of the culture shock and increased people’s ability to function independently, including some who work remotely in their own jobs and continue to maintain their foreign standard of living. Shopping online with free delivery from Amazon or Marks & Spencer was unimaginable then. WhatsApping around the world and staying in close contact in real-time with friends was a fantasy for us. But trade my experience for now? I think I’ll keep mine.

Cultural adjustment

Learning Hebrew is needed not just for functionality and employment prospects. The issue is that this is a different country, a different continent, a different culture. People sometimes go on a bar mitzvah or a Birthright trip, and after sticking to a well-traveled tourist route, they may develop an expectation that moving to Israel is like going to a different community in New Jersey without a good deli, but with better weather.

It is not. Israel is in the Middle East. The country is largely populated by people from Middle Eastern countries. On first impression, coming to polyglot Israel is like being dropped into a crazy casbah from a different time. Mostly, people’s parents and grandparents did not speak Yiddish, their cultural familiarity is not Eastern European, and their fallback slang may be in anything from Ladino to Arabic to Farsi. And these are just the Jews.

Making aliyah at any time of life will bring a period of culture shock. Now three years after moving to Israel, semi-retired psychologist Ze’ev, formerly Don, Uslan came to Israel after some 40 years in Seattle and many years in Los Angeles before that. He came with his wife, journalist Judy Lash Balint Uslan, a veteran olah. They are now still honeymooners in a second marriage for both; he has adult sons and families in Seattle, and she has a daughter and family in Seattle, and a son with his family in Jerusalem.

Initially, Ze’ev was put off by the rudeness and noticed that people yell a lot compared to the “idyllic” life he came from. He thinks maybe New Yorkers might find this less jarring, but politeness and “niceness is missing.”

Yet, despite the variance from the romantic views of Israel that he had from Jewish Agency stereotypes he had absorbed from tree-planting and folk tunes, Ze’ev says he is “entranced to be here.” His life stateside was successful in all the known avenues of materialism, degree-seeking and a fulfilling professional career. From the Reform Judaism in which he was raised, he gained basic Jewish values and has a strong interest in family history that had origins in Belarus and Ukraine.

Ze’ev, whose practice mostly comprised patients who had experienced trauma, views Israeli society as one based on trauma. There are multiple sources of difficulties and stresses, and generally, one must make the best of things as much as possible. He quips that he has what he has coined as “Israel adjustment disorder” from his own perspective. The differences between his former life and current one are shocking, he says. They range from the ease of consumer society to the wide-open familiar natural vistas.

It has come as somewhat of a surprise to Ze’ev that it is “exciting to live here… overwhelming and dynamic.” Judy joins in and suggests that “moving to Israel brought with it a different vision of what Jewish life could be.” Their old communities were more concerned with Judaism than with Israel, so it has been a path of discovery for him.

The path that is unfolding is guided in part by Judy. Raised in Northwest London in a very Zionist family, she was involved in the Bnei Akiva youth movement from age seven. She first came to Israel immediately after high school, in a gap-year program, to Kibbutz Be’erot Yitzhak. In some ways, she says, the adjustment for her was less abrupt.

“England was a less affluent country in those years; non-Americans may have had fewer bumps, and the students who were raised in the 1960s and ’70s gravitated toward socially-conscious issues, with a few misfits in the mix,” she says with a laugh.

Judy made aliyah after her children were already grown, at age 45, after spending 15 years in an aliyah group that was started in the early 1970s in Seattle. She laid the groundwork and “prepared my kids that I was going… Leaving family behind is the hardest thing. It’s hard to strike a balance.” For Judy, “it was an affirmation of a dream and a set of values.”

As intern coordinator at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs for more than 10 years, she observed that the interns come following 10-day Birthright programs and “know nothing of Judaism.” The internship provided them with a framework so they could stay longer, and a significant number also made aliyah.

“Their level of knowledge about Israel was extremely limited. They were attracted to Israel as a small country where you could see your influence… For them, Jerusalem was intense. Tel Aviv is dynamic, an open society still being formed and exciting.” Most were in college, on their junior year abroad, post-college or job-hunting, Judy recalls.

She adds that is important to have an “adaptable personality.” She continues, “From social media, people may get an expectation that Israeli society is a reflection of themselves – it’s not, though. It’s completely different.”

<br>Acquiring Hebrew

Was it easy being an adult and not being able to formulate a simple request in Hebrew? Was it easy not having the vocabulary of a two-year-old? In a word: NO. I made tons of mistakes, social faux pas and cultural errors. But for my part, I also started feeling more comfortable incrementally and – classically – learned to adjust from our kids. My husband, for his part, additionally experienced the great societal equalizer – serving in the IDF.

Young people in particular must learn Hebrew. It is necessary for employment. Job opportunities are very different when an applicant is competent in Hebrew. The immigrant also comes with the advantage of their mother-tongue language, which is a great asset in many jobs, particularly when many offices have global customers.

Hebrew is necessary to be able to be part of Israeli culture, to understand the country, to be a part of the societal ebbs and flows whether on the community or on the national level. And, to steal a quote from the movie My Big Fat Greek Wedding, “Don’t you want to talk to your mother-in-law?” Indeed, for singles, it might be hard to anticipate, but one day you may be part of a large Hebrew-speaking hamoula (slang for “clan”), and as the years roll on, that is likelier than you might realize.

Beyond being a person who can come home with cottage cheese as the choice you intended rather than white cheese – in identical containers, just to keep you on the ball – you also really want to go to a Hebrew movie and laugh along when everyone else gets the joke. The translations leave the screen too quickly; and, frankly, once your Hebrew is good enough, you will learn that they can be full of errors.

More to the point, your life will be enriched with Hebrew. After too many years of resistance, I have learned to love the beauty of the language and regret that my stubbornness extended so long.

Without Hebrew, your life is restricted to English enclaves, English culture; life stays inside an English bubble. It is comfortable but limiting. Ze’ev adds that it is hard for him to meet Israelis and that he would be interested in being matched with an Israeli volunteer to help cross the cultural divide and help him get a deeper understanding of Israel.

Ze’ev, who is not yet fluent, found that he was being “too earnest; I tried too hard in ulpan. I was using my old study formulas, and that didn’t work… I learned I had to take it slower, be more natural. I couldn’t compete, or rush the acclimatization. I had to be patient. All my striving didn’t make it happen any faster. I don’t need to understand why, but just to accept it.”

Any Israeli kid would agree, you have to learn lizrom, to go with the flow. ❖

This is the first in a two-part series on the realities of aliyah.

Winning the Hebrew battle

To speak Hebrew, you need to hear Hebrew. All the time. Immerse yourself; dive right in. Here are some suggestions:

- Keep the radio on in Hebrew all the time. Try Army Radio. Or Kol Yisrael. And commercials, especially commercials, till the jingles become ear worms.

- Go to plays in Hebrew (or live stream them) – ones that you know very well in English, such as Romeo and Juliet or any musical you know by heart.

- For the advanced, watch Hebrew TV. Start with kids’ shows, then move on to translated musicals and familiar movies.

- Make a language hevruta and team up with another person. One speaks in their native tongue, Hebrew, and the other answers back in their native English. Both gain.

- Find a kid to read easy readers with – really easy ones. Children’s books seem like you ought to be able to handle them, but looks can be deceiving. Sometimes they include poetic phrases or biblical idioms. The little tykes can do it, but you should take it slow. Even baby books have new vocabulary. You may have a PhD in quantum physics, but a book for a three-year-old is not your level – yet. Very humbling. Have patience. Especially helpful is a pictionary. Let the child read to you. Very slowly. Listen. I mean really listen.

- Get the classic songbook 100 First Songs that comes with a CD or equivalent. Listen till you go crazy. You’ll recognize and know the canon of Hebrew childhood and holiday tunes.

- Read Hebrew newspapers. Start with “lite” versions; for instance, the one published by The Jerusalem Post. Read just the captions, then add headlines of current news and articles of personal interest, such as travel, cooking and sports. After headlines get easier, add the texts. When you buy weekend newspapers, always have a Hebrew paper in the pile, even a free local one, if only to read the ads. Or get a magazine of an area of personal interest, but in Hebrew – cooking or geography or design. Pick something.

- The highly motivated and now fluent Hebrew speakers I know obsessively made lists of new words with translations, and then made themselves flashcards to practice. (They also married native Israelis.) Just putting that out there.

- youtube has #learnhebrew #easyhebrew videos: Linguistix Pronunciation www.youtube.com/watch?v=yNJtAibUeOc

- Guy Sharett of streetwise Hebrew discusses Hebrew-language trauma, Hebrew and culture, learning from graffiti, a method to learn in a different way. www.youtube.com/watch?v=DFKjWDyHTUA

- Here’s an easy Hebrew video with Hebrew and English subtitles: www.youtube.com/watch?v=xF2tdJ2Ojjo

- Spoiler: One ulpan is never enough. People take successive ulpans for years and each time gain more proficiency. But nothing beats working in Hebrew, such as sending emails in Hebrew (Google translate has gotten better). And if your children and their friends didn’t improve your Hebrew, your grandchildren will.

The writer is producing an artist's book memoir entitled: Life-Tumbled Shards. It is comprised of original artwork, reflections on the loss of the couple's adult daughter to illness and contrasts between her early years in the US and her Jerusalem life.