Historian Istvan Deak wrote of Eugenio Pacelli, later known as Pope Pius XII: “Fearful of Hitler’s wrath, the pope barely raised his voice against Nazi racism … and spoke even less against Nazi antisemitism.”

Others noted that the pope remained silent while more than 1,000 Jews were arrested in Rome on October 16, 1943, to be deported to Auschwitz, and when 335 civilians were executed in caves outside Rome known as the Fosse Ardeatine. In fact, he never specifically condemned Nazi atrocities.

“Despite claims by the pope’s defenders that a behind-the-scenes protest on his part led to an end to the roundup of Rome’s Jews following October 16, the action of the capture of the Jews did not suffer any pause,” wrote one commentator. “On the contrary, it continued by the Germans in an undisturbed manner.”

And this unforgiving verdict: “As a moral leader, Pius XII must be judged a failure. He had no love for Hitler, but he was intimidated by him, as he was by Italy’s dictator … Pius XII clung to his determination to do nothing to antagonise either man. In fulfilling this aim, the pope was remarkably successful.”

The Pope At War

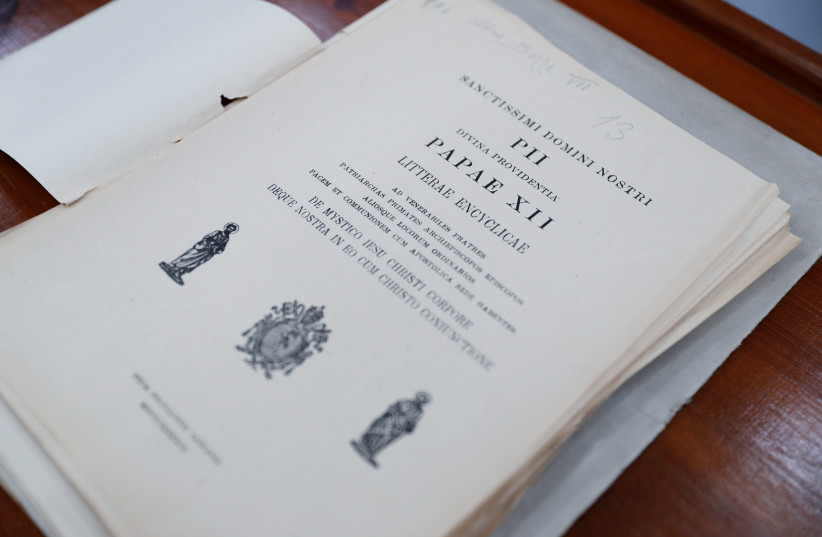

These and other commentaries are included in The Pope At War by American professor David Kertzer, a scholar of the Vatican who has written 13 books. This recently-published volume, which includes 100 pages of archival sources and references, is based on thousands of documents which were opened in 2020 after being sealed upon Pius XII’s death in 1958 and stored in Germany, France, Britain, the US, Italy, and the Vatican.

Kertzer explores what he describes as falsehoods regarding one of history’s most controversial popes and the extent to which he spoke out – or didn’t – against the genocide that was perpetrated on his watch. According to Kertzer – whose Pulitzer Prize-winning The Pope and Mussolini is regarded as a definitive work about Pius XI – the case against Pius XII is overwhelming.

The controversy is “largely focused on his silence during the Holocaust, his failure ever to clearly denounce the Nazis for their ongoing campaign to exterminate Europe’s Jews or even to allow the word ‘Jew’ to escape from his lips as they were being systematically murdered,” he writes.

An extraordinary revelation is that Hitler had a direct line of communication to Pius XII, “so secret that not even the German ambassador to the Holy See” was aware of it. The liaison was Prince Philipp von Hessen, a Nazi Stormtrooper whose grandfather was German Emperor Frederick III, great-grandmother was Britain’s Queen Victoria, and wife was Italian King Victor Emmanuel’s daughter. Von Hessen repeatedly conveyed Hitler’s request that the pope say nothing about the “racial question,” in return for which the Church would be left in peace.

The pope consistently gave speeches that appeased both the Axis alliance and the Allies, with Germany interpreting his ambiguous words as criticism of the Treaty of Versailles. Yet Kertzer does mention a 1941 journal entry by Angelo Roncalli, the future Pope John XXIII: “He asked me if his silence regarding the Nazis’ actions is not a mistake.”

As evidence of Nazi massacres mounted, appeals to the pope to protest also escalated – from Brazilian, Belgian, US, British, Polish, Dutch, Norwegian, Czech, and Yugoslav envoys among others. Even Peru appealed. And a request by Jerusalem’s chief rabbis for a meeting went unanswered.

Regarding his primary duty as protection of the Church, the pope’s actions were largely informed by his belief that the Axis powers would prevail, writes Kertzer. He appealed to the Allies not to bomb Rome – despite remaining silent when London was bombed – insisting that Rome was free of military activity, even though Germany and Italy used it as military headquarters.

A telling message to Berlin from Ernst von Weizsacker, Germany’s ambassador to the Vatican, on March 29, 1944, stated: “The pope is working six days a week for Germany; on the seventh, he prays for the Allies.”

And on June 2, 1945, after Germany’s surrender, Pius XII delivered a speech which focused on what he claimed was a Nazi campaign against the Church. “He made not the briefest mention, no mention at all, of the Nazis’ extermination of Europe’s Jews,” writes Kertzer. “If any Jews had been in those concentration camps … one would not know it from the pope’s speech.” ■