Ilya Galant was an important (but little known) Jewish-Russian-Ukrainian historian and political liberal, who wanted to legitimize the rights of Jews in Russia and “normalize” their presence in Ukraine. In order to do this, he interpreted history creatively, showing Jewish-Ukrainian friendship as well as Jewish contributions to Ukraine. He also appealed to the Russian intelligentsia to foster a liberal coalition of forces in favor of Jewish rights.

Galant depicted a Ukrainian-Jewish synthesis, giving a portrait of mutual friendship, codependency, and binational unity. For Galant, the myths of eternal hatred between Ukrainians and Jews were just that, myths.

A fresh examination of historical documents showed him that the two nations actually had much in common, including their love for the land and shared struggles against oppressors.

Almost nothing has been written about Galant’s historical work. He was born in Nezhin, Ukraine in 1867 and likely died at the Babi Yar Massacre in 1941. As a boy, he received a religious education. In Nezhin, he became close with history professors at the local university and spent several years studying in the university library. In 1890, he moved to Kyiv and taught history in high schools. As a historian, he published a number of important documents and studies regarding accusations of ritual murder, violence in 1648, and Russian-Jewish relations in the 19th century.

Galant would perhaps have become a familiar name in Eastern-European Jewish historiography if Jewish autonomy had succeeded in Ukraine and throughout Eastern Europe. But things did not work out that way. While the loosening of central power at the end of World War I led to the fall of tsarism and the rise of an independent Ukraine, by 1921 most of the former Russian Empire, including Eastern Ukraine, had reconstituted itself as the Soviet Union.

Characterized by a Communist ideology and a strong central government, the state coopted Ukrainian nationalism and forcefully oppressed Jewish religious and national identity (with a few exceptions). In East-Central Europe, in Poland, Romania, and the Baltic states, Jewish nationalism was shown as politically powerless.

Galant’s politics and his readiness to link Jews with other subalterns against the central power had lost, and instead of serving as a model for a new type of historiography focused on united minorities, his version defined him as a hold-over, a bourgeois, and expendable.

For us today, he represents one of those “paths not taken,” a Jewish historian who ran aground on the shoals of the history that he himself had tried to shape differently.

During his career, Galant managed to gain access to rare documents in Russian archives: the Kyiv city archive, the archives of the state governor, and even police files. Clearly, he had connections in high places; he befriended the academic elite in Nezhin and Kyiv, and for a time in the 1890s, he served as the private secretary to Samuil Brodsky, the well-known Kyiv industrialist. In addition, with his knowledge of Hebrew, he had access to pinkasim (communal ledgers), rabbinic manuscripts, community metric books, and other Jewish documents.

He embraced a Ukrainian-Jewish identity that broke with other Jewish historians who spoke of Jews as a unified community throughout the empire. A unique figure, Galant focused exclusively on Jewish Ukraine and he sympathized with Ukrainian nationalism. An essential assumption through all his work is that, as a concept, “Ukraine” included the Jews who lived there. In this way, Galant was situated at a unique intersection, where the birth of the national struggles in the Russian Empire – Ukrainian, Lithuanian, Jewish – was announced and liberalism – the values of a multi-cultural democratic Russia – was growing in popularity.

Perhaps the most innovative dimension of Galant’s work is his portrayal of a Jewish-Ukrainian synthesis because it runs against the grain in Russian and Jewish historiography. In nineteenth-century Russian historiography generally, Jews, if they are depicted at all, are depicted overwhelmingly as profiteers who play a nefarious role exploiting the hard work of the peasant. Such was the case with the influential Ukrainian historian Mykola Kostomarov. Rarely did non-Jewish historians depict Jews positively, with the exception of Sergei Bershadsky, who in his studies of Jews of Russia’s Northwest showed the value of Jews for economic and cultural progress in Russia.

As one would expect, in Jewish history, tackling the subject of Ukraine is complicated. To be sure, many leading historians such as Heinrich Graetz and Simon Dubnov emphasized violence and antisemitism, focusing on the Khmelnitsky Uprising. In contrast, an unconventional line emerged that emphasized the propitious conditions that attracted Jews to Ukraine and had permitted a dynamic civilization to form and flourish despite intermittent violence. Historians such as Avram Harkavy, Mikhail Kulisher, and later Saul Borovoi belong to this group.

Blaming others

As mentioned, Galant perceived a unity of Ukrainian-Jewish interests where others found discord. For example, he set the blame for anti-Jewish violence firmly at the door of the reigning powers; in one case the Poles and in the other the Russian government. In nearly every case he shielded Ukrainians from blame. This position is indefensible and contradicts the historical evidence, but Galant held firm, marking himself as a friend of the Ukrainian people in their quest for national self-consciousness.

Just as other Jewish leaders did in places where competition over Jewish loyalty had become contested between the central and local powers, Galant was torn. He had great sympathy for Ukrainians and their national goals, but also identified with Jewish political demands. He wondered whether Jewish progress should be yoked to Russian liberalism (multi-national Russia under Russian control), to Ukrainian autonomy, or to the Jewish national struggle.

Galant’s attempt to be all things to all people inevitably failed. It led to flawed historical writing in the sense that today, when one reads Galant, one must weed out fact from imagination. His ideological problem was that all the parties involved (Russian government, Russian people, Ukrainians, Jews) could not easily be placated and some interests were irreconcilable. For example, Galant did not reject the hope that historical study could contribute to the attainment of rights for Jews in the Russian Empire.

However, nothing Jews did could convince the Russian government to loosen control. At the same time, Ukrainians composed a rising nationality seeking to expand their national profile and right to self-administration, including the Ukrainian language in schools and cultural activities. Jews, themselves a persecuted people, also started to formulate separate demands. Desire for Jewish cultural autonomy was spreading and taking shape. For a short time just before 1905, Galant himself even trumpeted Zionism, believing that Jewish national identity would enhance Jewish self-respect and perhaps some part of the Jewish masses could attain gainful employment in Ottoman Palestine, though Ukraine remained the focus of most of his personal and professional attention.

In an early article entitled, “On the History of the Settlement of Jews in Poland and Ukraine in General and in Podoliya in Particular” (1897), Galant made a claim that he repeated throughout his life, that Ukraine offered excellent conditions for Jewish life because it “did not have that intensive and sharp character, as in Western Europe.” He meant that the persecution of Jews that was constant and unremitting in Western Europe was relatively absent in Ukraine. In Ukraine, there were isolated tragedies, but they were overwhelmingly rare and uncommon. On this point, Galant made sweeping generalizations:

“Only ancient Rus appears a happy exception (relatively speaking) in this regard. Despite arriving at the time of the first Rurik rulers, and perhaps even earlier, Jews were not subject to personal persecution and expulsions, did not experience those physical tortures and spiritual humiliations that their co-religionists in Western Europe had to endure endlessly. But, saying this, I do not believe that Jews were always blessed with total prosperity, but life passed peacefully and was not disrupted by the intrusion of the wild crowd.”

Galant was aware that the most difficult question for a Jewish historian of Ukraine is how to treat the uprisings, the Khmelnitsky Revolt in the seventeenth century, and Haidamaky – the actions of bands of Ukrainian warriors in the eighteenth century. The conundrum is this: Ukrainian historians have lauded the violence against Polish rule as an original expression of Ukrainian national identity, yet for Jews, these events were tragedies. Jews were widely victimized, murdered, raped, enslaved, and their property pillaged. Although Galant acknowledged that Jews owed their livelihood to collaboration, or better, subordination to Polish economic and political needs, he maintained that Jews were collateral victims and not the focus of Ukrainian hate.

According to Galant, sources from the time agreed with him:

“One can only assert that Jews innocently suffered during the Haidamaky, since even in the literature hostile to Jews, there is, it seems, no mention of Jewish antagonistic acts toward the Haidamaks. Even the Archimandrite of Montrenin, Melchisedek Znachko-Yavorskij, whom many consider the leading villain in Haidamak crimes, in his lamentations and complaints against persecutions toward Russian Orthodox Christians and the Russian Orthodox church by Poles hardly speaks at all about Jews.”

In contrast to anti-Jewish sources, Galant explained the strife as a result of a triangular conflict of interests: Russian, Polish, and Jewish. He gave weight to religious, ideological, and ethnic motives:

“However, there can be no doubt that the Russian element in Poland is guilty of the two massive catastrophes in Jewish history, the Khmelnitsky Revolt and the Haidamaky. These catastrophes were rooted in a national, spiritual and economic antagonism between the tragedy’s three participants, the Polish nobility, Jews, and the Russian peasantry.”

It is significant that Galant does not mention Ukrainians or Ruthenians, but calls them “Russians.” Whether Galant wanted to say anything special by using this terminology is difficult to say. In any case one can interpret it as an attempt to portray Ukraine as naturally part of Russia, thereby underscoring Galant’s liberal position in favor of the multi-ethnic Russian empire. However, this position leads Galant into self-contradiction, since, by implicating Russians and saying that Ukrainians are Russians, he inevitably blamed Ukrainians for violence against Jews.

Galant consciously pointed out the Jews’ vulnerabilities, their precarious position as the landlords’ agents, as well as the suffering Ukrainians:

“Jews in the socio-economic life of this region worked in a very dangerous and risky position. They found themselves between… a despotic nobility, ignorant and without borders in passions and caprice, and plebians, who are persecuted, forgotten, tortured and left to the whims of chance.”

In contrast to myths regarding the extensive violence against Jews during the Khmelnitsky Revolt, Galant argued that violence was not widespread nor were the consequences long-lived. One way he emphasized this was through his writings on the successful rebuilding of Jewish communities following such disruptions.

Dispelling falsehoods

Galant was not afraid to deal directly with Jewish suffering in Ukraine because he viewed it as minor compared to other countries. Yet, he still did not make an effort to incriminate Ukrainians. He nearly always found a different persecutor. Galant’s research shows that the Catholic Church extorted onerous sums from Jews. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Jewish communities fell on hard times and were unable to pay their tax obligations. In such cases, they were forced to borrow at impossibly high rates of interest and put up their most valued objects as collateral – sometimes even their synagogues. In many cases, the Polish Catholic Church fleeced Jews mercilessly, as Jews had little choice but to borrow from this exclusive source of liquidity.

Galant’s use of documents helped to dispel falsehoods and legends that had gained the status of truth. For example, he explained that many people had come to believe that Ukrainians were indebted to Jews to such a degree that Jews owned Uniate churches and rented them to the congregants. Galant explained:

“Accusations exist, false, unverified, scientifically or documentarily unproved, that however implicate not only those against whom these were originally brandished, but also their distant descendants. These accusations, having been born and come to life in some unknown way, are legends that, having completed their trip through many generations, acquire thereafter the consistency of a true fact, an inconvertible truth not only in the eyes of the ignorant simple people, but also scholarly authorities.”

Galant maintained that there was no evidence for such a claim in all the documentation regarding Jews in Ukraine. Only Cossack chronicles assert Jewish control of churches, and, he remarked, these sources had come under considerable criticism. Acknowledging folksongs, he nonetheless noted that:

“It is highly risky to draw serious conclusions on the basis of folk songs exclusively.”

Galant gave an explanation for such specious claims, speculating that the sale of alcohol by Jews became associated with churches because Ukrainians held their parties and life-cycle events in churches. Thus, it would have seemed that if they could not afford liquor, then they could not hold their parties. From this, one could conclude that Jews controlled the churches. Galant maintained that these accusations were likely used to agitate the population and motivate the Khmelnitsky Revolt. However, what was first used as propaganda was later interpreted as truth by even the most highly respected Ukrainian historians.

Galant’s attempt to exonerate Ukrainians cannot be left unnoticed. His assertions collide with other treatments of the same events both in his time and today. Of course his reasons are transparent: he wanted to accuse a few individuals or blame later historians for antisemitism in order to preserve in his own mind the legitimacy of a Jewish-Ukrainian political alliance. Although it is impossible to fully agree with Galant, it is possible to sympathize with his desire to break free of stereotypes and revisit anti-Jewish events to check how much of the myth of Ukrainian hatred was true and how much was a subsequent construction. For Galant, most is a construction, yet just because Ukrainians were themselves victimized by others does not exonerate them from also persecuting Jews.

Blood libels

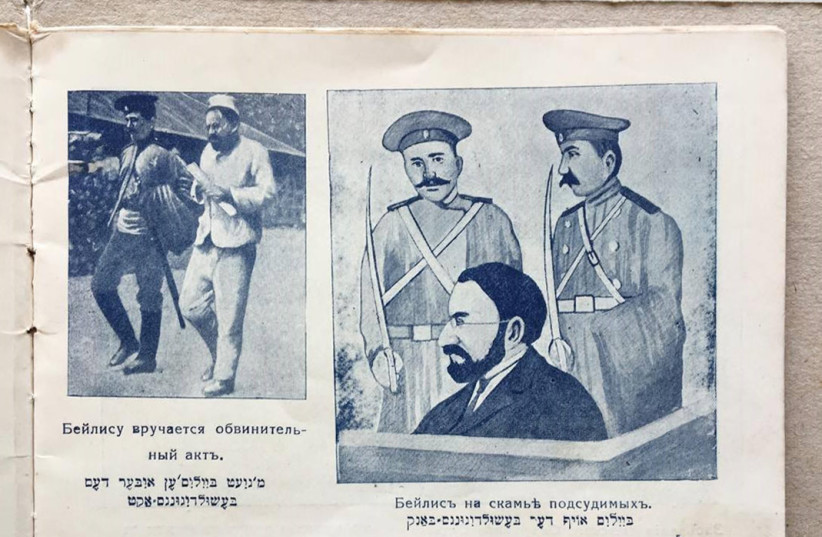

In his studies, Galant treated blood-libel accusations in detail. Examples included his articles, “Victims of a Ritual Accusation in Zaslav in 1747 (According to Documents of the Kyiv Central Archive)” and “The Ritual Murder Trial in the City of Dunai in 1748.” It makes sense that he would take an interest in ritual murder, as the phenomenon had reemerged under Tsars Alexander II and Nicholas II, as well as in Europe (the Tisza Eslar case is an example). In Russia in 1879, the government orchestrated a blood-libel trial in Kutais, while in 1898, the Blondes trial was held in Vilna. The notorious Beilis Trial took place in Kyiv from 1911 to 1913. Galant’s general contribution in the context of blood libels was to show the patent falsity of such charges, as early as in the fifteenth century.

In his article about Zaslav, Galant portrayed that trial as one of a large number of such actions by Poles against Jews:

“The middle of the eighteenth century was characterized in the history of Polish Jewry by the extreme numbers of ritual trials that would end in the majority of cases with cruel executions.” However, these accusations hardly began as late as the eighteenth century. Relying on the work of Sergei Bershadsky, Galant lists incidents through the centuries: “…it was precisely the Cracow pogrom of 1407 that was caused by a false rumor of a ritual murder.” Then there were cases in 1564, 1576, 1617, 1619, 1636, 1639, and 1690—“all these were brought against Jews with venom and included a transgression of existing laws and legal rules.”

Again Galant showed Poles as the source of Jewish pain. With Jews, the Poles took advantage of their power to construct a convenient scapegoat for the failures of Polish rule, Polish economic problems, and the religious infidelities of the Catholic Church. Galant’s point regarding the Jewish-Ukrainian conflict was that both nations were victims, poor, defenseless, and suffering. Each nation thought the other guilty for its pain. Poles, who in Galant’s view actually bore responsibility for the difficult conditions of life in Ukraine, unleashed Jews and Ukrainians on one another.

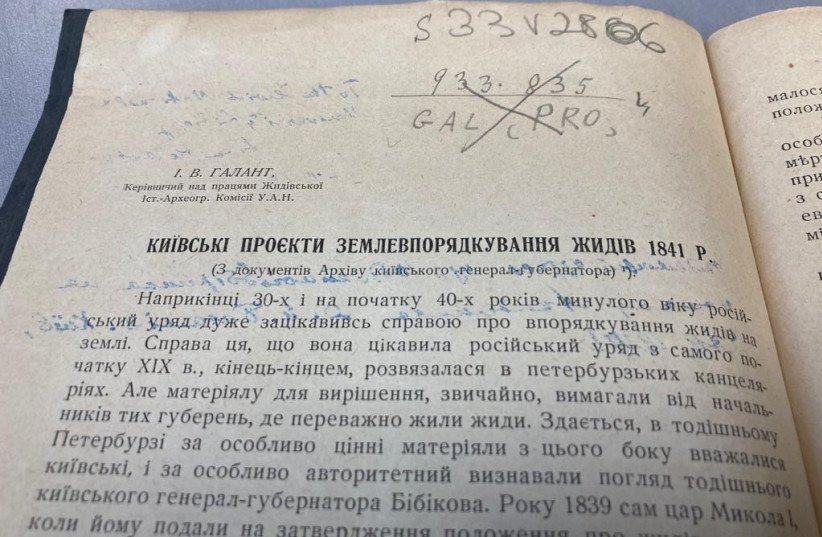

Soviet rule and the Galant Commission

Galant’s work in the Soviet period did not differ much from his pre-revolutionary oeuvre. Despite publishing in Ukrainian and with other Ukrainian scholars, Galant took as his subjects the Russian state and Jews, violence against Jews in the nineteenth century as well as the first decade of the twentieth century. He relied on archival materials he had gathered earlier and was unable or unwilling to draw on the new proletarian sources and approaches to Jewish history. Therefore, he resembled the “bourgeois” historians of the pre-revolutionary era. During the 1920s, Galant published a number of articles in Ukrainian, while also leading the Jewish Historical Archeological Commission, which became known as the “Galant Commission”, which produced two well-known historical volumes. Galant was the commission’s only paid employee, and it is worthwhile looking at his role carefully.

While many scholars left Russia as soon as they could after 1917, Galant stayed. In fact, he succeeded in winning the confidence of the new powers that be. In 1919, in Kyiv, a group of historians that included Galant and Benzion Dinaberg (Dinur), A. Kagan, and Jacob Izrailson asked permission to organize a Jewish Historical Archeological Commission within the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. The group made an appeal:

“Jews in Ukraine have a history many centuries long. The fate of Jews was closely linked with the fate of the Ukrainian people. Jews played a significant role in the economic and cultural life of Ukraine. And despite all that, there still does not exist a systematic history of Jewish history in Ukraine. The absence of such a history has sparked a great deal of confusion and created many false ideas about Jewish activity in Ukraine and interaction between the Ukrainian and Jewish nations.”

According to Victoria Khiterer, Galant was the initiator, and the project won the sympathy of respected scholars including the secretary of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. A program was formulated to collect, describe and publish relevant historical materials, yet the main goal of the academic authorities was to impose the use of Ukrainian as the language of scholarship.

The language issue emerged as a crucial problem for the Jewish Historical Archeological Commission. The two volumes that the Commission published in 1929 and 1930 were replete with the word, “zhid” (kike), which in Ukrainian as well as in Russian had negative connotations. Galant expressed a preference for “evrei,” a Russian word that came from the ancient word for Jew, “ivri,” but he was rebuffed. Saul Borovoi explains the language context:

“A great deal was shocking in the collection; above all, the title, ‘Zhidovsky’ [Kike]. Throughout the entire collection the word ‘evrei’ [Jew] was not used, everywhere one read ‘zhid,’ ‘zhidovsky.’ Galant told me that one of the patriots of the Ukrainian language declared that there is no word ‘evrei’, but only ‘zhid’; that this word, he maintained, does not contain any insulting nuance. ‘To ruin Ukrainain through the introduction of the ‘foreign’ word ‘evrei’ is not allowed.’ (I will note, turning aside for a moment that in the Central Rada [parliament] that the representatives of Jewish parties joined—Zionists, Poale-Tsion, Bundists and others—the Jewish deputies announced that the word ‘zhid’, used by several orators, was unpleasant for them. The head of the Rada, Grushevsky therefore announced that, although the word ‘zhid’ does not contain anything insulting in Ukrainian, he asks the Rada’s orators not to use this word, but say ‘evrei,’ ‘evreiskii’…).”

Since many of the documents deal with Russian matters, the use of “zhid” conveyed disrespect and disdain.

More lethal were objections from Communists on ideological matters. In the mid-1920s, the Commission came under severe criticism as a bastion of anti-Soviet activity. Its critics were orthodox Marxists, especially Nahum Shtif, the linguist who had played an instrumental role in organizing The Jewish Scientific Institute (YIVO) in Berlin in the early 1920s. Shtif secretly posted denunciations with party apparatchiks. While Shtif’s motives are uncertain, it is known that he was unable to find steady gainful employment in Berlin and encountered a difficult situation. As did many émigrés, he was offered good conditions for scholarly work if he agreed to return to Soviet Russia. It is entirely possible that, when he arrived in Kyiv, he realized that Galant was an obstacle to the leadership and that it was necessary to remove him.

The attacks on Galant proved successful and he was fired from his position in the Jewish Historical Archeological Commission. By the early 1930s, he was also banned from working in archives. His life as a historian was over. According to Saul Borovoi, Galant died as a victim of Nazi murder at Babi Yar, September 29–30, 1941. Little is known about Galant between the years 1930 and 1941.

Legacy of a historian

At least one person wrote caustically about Galant during his glory days in tsarist decadence. Saul Borovoi provided this devastating portrait:

“Ilya Vladimirovich was full of self-respect. He did not walk, but carried himself like a full wineglass which should not spill. The old members of Kyiv said that in the pre-revolutionary years he sauntered along the Kreshchatik every day in a top head, finishing his walk in the cafe ‘Samodeni’, where he would drink a cup of coffee and where his admirers waited for him and to whom he would tell his ideas and political prognoses.”

This description of a vain man, who yearned for status and used historical study as a means to attain it, possesses a sense of truth, yet Galant produced serious works of history, and his production appears more than merely a means to satisfy his ego.

It should also be noted that Galant reflected his own time, which was eclectic, unstable, characterized by a rise in national feeling and shifting cultural politics. He tried to hold firm to liberalism, but he swayed with the winds of nationalism, and was ultimately cut down, another victim of Soviet academic life. At the same time, he published important materials and offered his own conception of Ukrainian-Jewish history as an example of harmony, the good life, and, despite all, a rare refuge for Jews in difficult times.

Although the majority of Ukrainian Jews have now left, there is still a chance today that Galant’s reputation will rise in an independent Ukraine, and he will find his place among other “unclassifiables”. It is a place, I think, he would have liked to be.

This article previously appeared on The Librarians, the official online publication of the National Library of Israel dedicated to Jewish, Israeli, and Middle Eastern history, heritage and culture. A version of it was originally published in Jewish History 34,4 (2021) 361–380 by Spring Nature.