Jewish sports fans, regardless of sport or team preference, share one universal experience: discovering new players and immediately wondering, “Are they Jewish?”

For decades, two men have provided the answers.

Since 1997, Ephraim Moxson and Shel Wallman produced the Jewish Sports Review, a print-only, bimonthly magazine identifying Jewish athletes from college through professional sports.

They rarely wrote in-depth profiles, and used few photos. The magazine’s calling card was its extensive and accurate lists of Jewish players, accompanied by key statistics and basic biographical information.

Their streak came to an end last month, when the octogenarian partners decided to call it quits.

The history of the Jewish Sports Review

Until then, the review survived in multiple iterations. Wallman published a version from 1972 to 1974, then for 20 years in the form of his weekly column for a Jewish newspaper in Indianapolis. Wallman and Moxson connected when Wallman, now 85, placed an ad in The Sporting News magazine. Moxson, now 80, began as a stringer for Wallman, and the pair ultimately partnered to relaunch the Jewish Sports Review as an independent magazine with a staff of two. They became good friends along the way, too.

Moxson, a retired California parole officer, and Wallman, a retired New York City middle school administrator and social studies teacher, dedicated four hours a day to their work, most of which came after they retired from their primary careers. Moxson called the magazine “unquestionably a labor of love.”

“It’s important to me because I have a very, very strong Jewish identity, as does Shel,” Moxson told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

“It’s important to me because I have a very, very strong Jewish identity, as does Shel.”

Ephraim Moxson

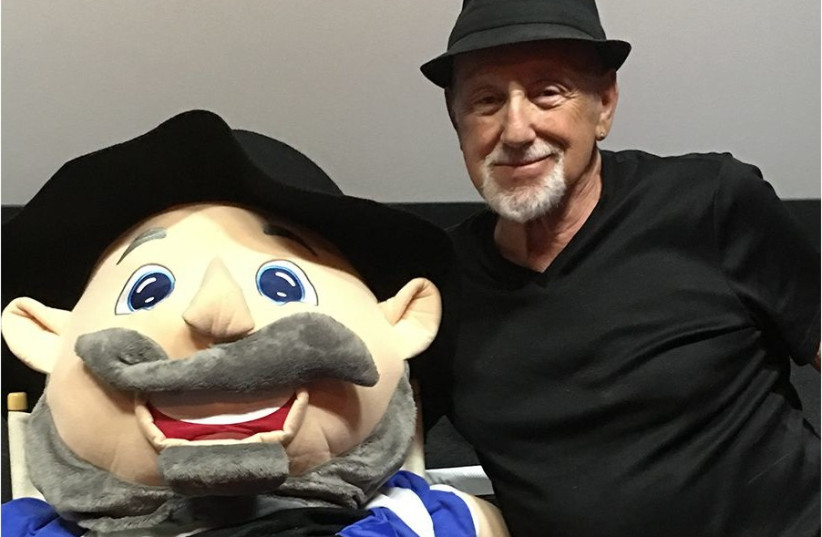

The pair have long eschewed the spotlight; Wallman did not respond to requests for comment, and Moxson reluctantly offered only a single photo to share. Instead, they have preferred to let their work speak for itself — and the work has been meticulous. For college athletes, they would pull every roster in six sports — baseball, basketball, football, hockey, lacrosse and soccer — across divisions. They’d scan the rosters for names or hometowns that could hint at Jewishness, and begin reaching out. They’d email the team’s sports information director and athletic director and contact the athlete’s family.

They highlighted everyone from high school All-American athletes to current professional stars like Atlanta Braves pitcher Max Fried and Washington Wizards Israeli forward Deni Avdija.

Who is considered Jewish?

The Jewish Sports Review operated on three criteria: the player must have at least one Jewish parent, cannot actively practice another religion and must agree to be identified as Jewish in the magazine.

“The fact-checking was the fun part about it,” Moxson said. “I mean, nobody’s going to do what we did.”

Unlike traditionalists who hold with matrilineal descent — that Jewishness is passed down through the mother — they did not care which parent was Jewish. Nor did they care how religious the family was. If the athletes said yes, they were in, and if they said no, they were out. No hard feelings, no explanation needed.

“You learn that not every Schwartz, Cone, Levy, Ginsburg, Feldman, Goldberg are Jewish,” Moxson said. “Surprising how many aren’t. If you find an athlete by the name of Schwartz, and he’s from Fargo, North Dakota, shouldn’t even really bother, he’s German.”

The debate about who is considered Jewish, and how to identify Jews, can often be a touchy subject in the Jewish world. On the one hand, America’s increasingly diverse Jewish community includes a growing number of people who do not have Jewish names or live in Jewish enclaves, meaning that the Jewish Sports Review’s criteria could easily miss Jewish athletes. On the other hand, some think the magazine has been too inclusive. During a presentation at the National Baseball Hall of Fame some years ago, a man wearing a kippah took issue with the Jewish Sports Review’s criteria, telling Moxson and Wallman that a player isn’t Jewish unless their mother is.

Wallman’s response? “Open your own magazine!”

“We just list them as Jewish because they’re identifying as Jewish, whether they’re religious or not,” Moxson said, whose parents immigrated to what was then Palestine in the early years of the 20th century. “I’m very, very Jewish. I’m the son of Third Aliyah Palestinian Israelis. My parents were Third Aliyah, my father was a Zionist fundraiser, Golda Meir came to my house. Nobody can question my Jewish identity. I just am not religious.”

In fact, Moxson added, the landmark 2020 Pew Research study on American Jews relied on a nearly identical definition of Jewishness. “Almost word for word our criteria. Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, I guess,” he said.

Throughout the years, the Jewish Sports Review built up a loyal readership, peaking at around 1,200 subscribers, some of whom had been with the magazine since its beginning in 1972. Moxson said their readers were predominantly older men, but that outside the Jewish population centers of New England, New York and Florida, they had readers from just about every state in the U.S., including Wyoming, Idaho and Arkansas.

“I believe particularly for those southern states, they got it because the communities are smaller there and they just wanted to know who’s Jewish,” Moxson said. “Can’t pick up the Jewish Journal [of Greater Los Angeles] in Tuscaloosa, Alabama.”

The magazine did not sell ads, and its price of $36 per year never increased. What did increase throughout the years, Moxson said, was the number of Jewish athletes at the professional level.

“People ask me why, and I say because there’s money in it now,” Moxson said. “Kid doesn’t have to be a doctor or a lawyer anymore. You can be a hockey player, baseball player and you make a boatload of money.”

Ultimately, after 25 years of identifying Jewish athletes from college to the pros to the Olympics, Moxson said their mission, and he hopes their legacy, was simple: to prove that Jews can be athletes like anyone else.

In other words, Moxson and Wallman set out to discredit the famous scene from the 1980 comedy “Airplane!” When a passenger asks for light reading, the flight attendant replies, “How about this leaflet — famous Jewish sports legends?”

“That became a thing that we had to contradict,” Moxson said.