Our climate is changing... rapidly.

Our summers burn hotter than ever before. Glaciers are melting, causing ocean levels to rise and threaten low-lying urban areas. We are deforesting, overfishing and overpopulating at alarming rates.

All these and other modern policies are threatening the sustainability of our planet. Should we curb human progress to protect planetary stability? How does Judaism and its traditions view this modern question?

As with many other modern issues, the answer is not clear. Created last, on the final day of Creation, man is the pinnacle of God’s universe. This entire vast and rich world was created to support the life of one supreme creature, in his search for his Creator.

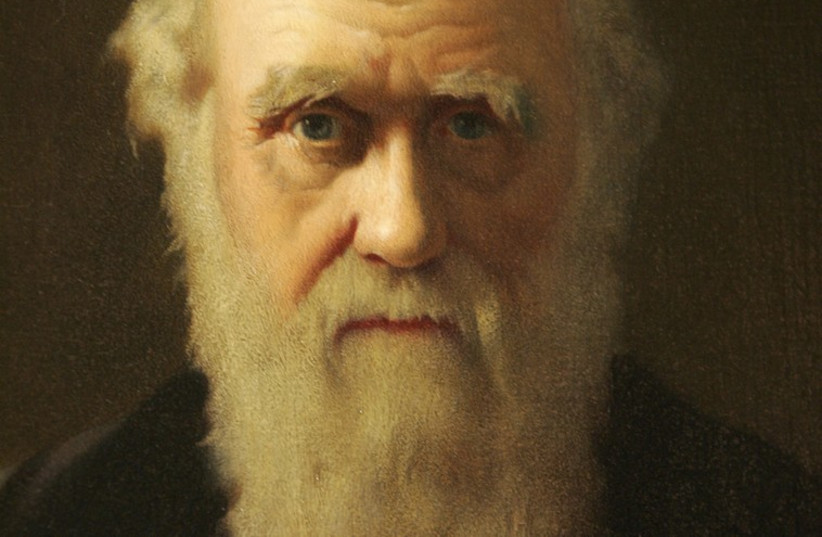

By claiming that all living humans belong to a unitary species with a single origin, Darwin didn’t just deny divine Creation. He also asserted equality between man and the rest of the natural world. If, as Darwin claimed, all species descend from a common evolutionary source, man possess no lofty or distinctive status.

Often, environmentalist agendas are premised upon this alleged equality between man and his world. Man has no more license to use the resources of nature than any other species, and he certainly doesn’t possess the right to harm a planet he shares with millions of organisms. These attitudes are completely incongruent with religious thought, which has perennially positioned man at the center of his world.

If anything, man is not just the apex of Creation; he is also a co-architect with God in refining Creation. In addition to intelligence, man is also gifted with creativity, and is expected to partner with God in perfecting a world that God left intentionally imperfect. We are divinely mandated to advance our world by harnessing the vast potential of nature. We are not just a superior creature but are vested with the ability and responsibility to employ nature and its resources on behalf of human progress.

However, given our elevated status, we face a very delicate dilemma. We are tasked with advancing God’s world, but, also, with preserving it. This dual mission was assigned to Adam while he still resided in Eden. A pristine world created by God was literally placed at Adam’s feet as he was cautioned “l’avda u’leshamra” – he must both advance it and preserve it.

For centuries, humanity never imagined that these two projects could ever clash. Our ability to advance our world could never endanger it. Nature lay beyond our reach and beyond our impact.

Yet, during the past few centuries, dramatic technological innovations have altered the equation. For the first time in human history, our ability to perfect human experience by harnessing nature will damage planetary stability. We have absolutely no traditions about this delicate dilemma. Should we curtail l’avda for the sake of l’shamra?

Here are a few factors to consider when assessing this previously modern religious and moral issue.

Moral sacrifice

Moral experience can be summarized as the willingness to sacrifice for the benefit of others. Selfish people reach decisions based purely upon personal needs, whereas morally sensitive people show willingness to surrender personal interest on behalf of benefit for others. Environmental conservation fits neatly into this moral equation: can we live less lavishly and more selflessly for the benefit of others?

The thing about moral behavior is that it is contagious. If we act moral in one sphere of life, we are more likely to act morally in other arenas. Similarly, selfish behavior is habituating. If we ignore concern for planetary sustainability, we are likely to become more selfish and less moral individuals in our general lives.

Long-term thinking

Living in a world of immediacy, we have become very shortsighted thinkers. We expect immediate results, and we often gauge our conduct based on the immediate consequences. Democracy and four-year terms encourage short-term politics with less concern for long-term considerations. Often, the most important decisions in life can best be appreciated with the hindsight of decades or even centuries. Long-term vision enhances many aspects of our lives, including relationships, personal growth and community experience.

Climate concern is an issue that requires long-term vision – the type of calculus we are less familiar with, but which is absolutely vital to our overall success. The environmental policies we adopt today will bear consequences only long after we all depart this world. We mustn’t be myopic or concerned only with the present, but must account for a future that is currently invisible. The ability to peer into the long-term future which is presently unseen is vital to religious spirit and to brave decision-making.

Jews live intergenerationally

As Jews, we live interconnected with generations we haven’t met and will never meet. We do not live isolated in our own century, but, instead, are part of a dynamic continuum of past and future. Our short lives are part of a larger redemptive arc which draws from the past and shapes the future. We are people of history and of the future.

People of history and of the future always gauge their actions’ impact upon their descendants. We certainly worry about the type of spiritual world we will deliver to our descendants. What stories will our lives tell long after we are gone, and our pictures hang on the walls of our descendants? Isn’t planetary well-being part of that story? Will we be embarrassed, if our lives of unrestrained excess create an uninhabitable world for our children?

There are no clear answers to the question of planetary conservation. Our tradition never faced these meta issues. That being said, there are various moral and religious values that should make us sensitive to the prospect of global conservation.

The writer is a rabbi at Yeshivat Har Etzion/Gush, a hesder yeshiva. He has smicha and a BA in computer science from Yeshiva University as well as a master’s degree in English literature from the City University of New York.

The Environment and Climate Change portal is produced in cooperation with the Goldman Sonnenfeldt School of Sustainability and Climate Change at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. The Jerusalem Post maintains all editorial decisions related to the content.