Researchers from Tel Aviv University, the University of California San Diego and Rome's Instituto Nazionale di Geofiscia e Vulcanologia have studied ancient pottery found in Jordan to understand the magnetic field that once prevailed in the Middle East between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago.

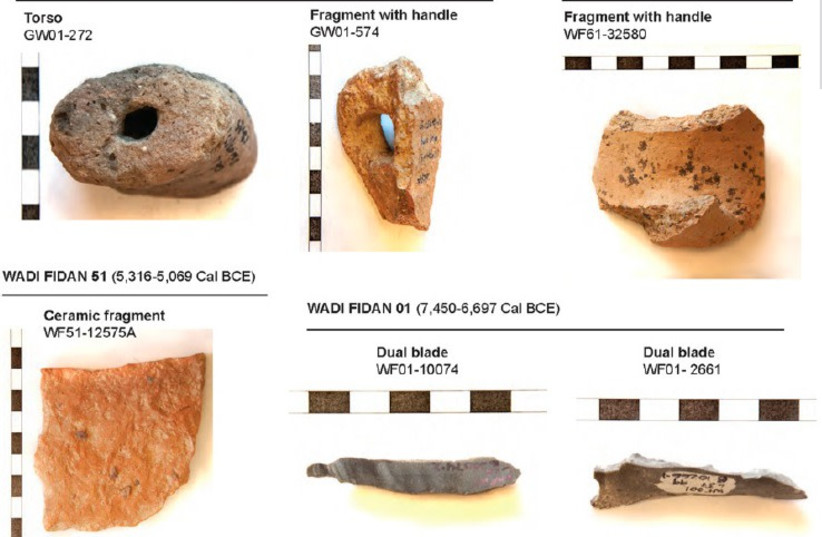

Led by TAU's Prof. Erez Ben-Yosef and UCSD's Prof. Lisa Tauxe, the research team studied pottery and burnt flints on which the magnetic field was recorded.

This is important, because as has been noted by prior studies, Earth's magnetic field, which protects the planet from radiation, has been weakening.

This, in itself, is nothing new. Back in 2017, Ben-Yosef in cooperation with experts from UCSD and Hebrew University of Jerusalem had led research by studying ceramics from ancient Judea dating from 8th century BCE to the 2nd century CE.

"The magnetic field that allows the existence of life on Earth as we know it," Ben-Yosef said at the time. "This field protects us from cosmic radiation and solar wind, is used in many animals to navigate and has a direct impact on many more processes in nature, such as the creation of isotopes in the atmosphere."

The field itself is something still shrouded in mystery, and Albert Einstein had said that understanding its source was one of the most important mysteries in all of physics.

Since it was first measured in 1835, Earth has lost around 10% of its magnetic field. In 2009, research conducted by Ben-Yosef found that 3,000 years ago, the magnetic field's strength was 2.5 times stronger than it is now.

But this new research, the findings of which were published in the academic journal PNAS, goes back even farther, because it used flint rather than ceramics.

"Working with this material extends the research possibilities tens of thousands of years back, as humans used flint tools for a very long period of time prior to the invention of ceramics," Ben-Yosef explained in a statement. "Additionally, after enough information is collected about the changes in the geomagnetic field over the course of time, we will be able to use it in order to date archaeological remains."

And these findings indicate that the magnetic field may be weakening, but it could also be reversed.

During the Neolithic period, the magnetic field was very weak, but recovered and strengthened itself in a very short amount of time.

Due to the current situation, this could be especially relevant.

"In our time, since measurements began less than 200 years ago, we have seen a continuous decrease in the field's strength. This fact gives rise to a concern that we could completely lose the magnetic field that protects us against cosmic radiation and therefore, is essential to the existence of life on Earth," Tauxe explained.

"The findings of our study can be reassuring: This has already happened in the past. Approximately 7,600 years ago, the strength of the magnetic field was even lower than today, but within approximately 600 years, it gained strength and again rose to high levels."

Judie Siegel and Daniel K. Eisenbund contributed to this report.