Palestine Police Inspector William Henry Bruce had finished a last round of drinks, most probably at Fink’s Bar off of Ben-Yehuda Street in Jerusalem, the capital of Mandate Palestine, on Thursday evening, October 17, 1946.

Bidding farewell to his drinking companions, he walked down toward Zion Square. He turned right along Jaffa Road and then, after some 150 meters, turned left up Queen Melisende Way (today, Helene Hamalka Street). He was headed for the rear entrance to the Russian Compound, where the Palestine Police Headquarters were housed.

But he never reached his destination.

EIGHT MONTHS previously, on Wednesday evening, February 27, at around 10 o’clock, two Palmah units attacked the Arab Legion camp located at Mount Canaan in Safed. Within some four hours, in a roundup of suspects, the two dozen members of the Palmah’s religious platoon based in Biriya, just a kilometer north of the town, were taken into custody.

Biriya’s lands were purchased in 1895 by the PICA, the Yiddish acronym for the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association, first founded by the philanthropist Baron Maurice de Hirsch, while an additional purchase was made in 1908 by Baron Rothschild.

The site had been populated in Talmudic times, and a nearby village of Naburiya existed during the First and Second Temple periods. Archaeological excavations revealed remains of a synagogue, one of the oldest in the Galilee, which was constructed after the Bar-Kochba revolt. In the nearby Ein Zeitim, Rabbi Joseph Karo composed his Shulhan Aruch in 1563.

Attempts were made to resettle the area in 1922. The Palmah sought to extend Jewish on-the-ground influence and set up an outpost there on January 8, 1945.

The building was constructed in the shape of a fortress. In addition to training activities and maneuvers, the JNF employed them as arborists and in removing stones while building terraces. All were members of a religious unit of the Palmah, given Safed’s character.

In addition, Jews secreted in from across the border in Syria were brought up from the Hula Valley to Biriya, which served as a way station, to be redressed and taught a song and some Hebrew before moved on to Haifa.

On January 31, 1946, 11 Palmah members, on their way to Kfar Giladi to participate in another immigration cross-border action, were detained by the British. Based on information that they were being held in Safed, a Palmah force attempted to raid the station and free their comrades. The February 5 attack, led by Aharon Spector, failed, and one squad, from Ashdot Ya’acov, retreated to Biriya and hid their weapons there.

As noted, on February 27, four Palmah members sought to reconnoiter the Arab Legion encampment at Mount Canaan, whose soldiers were also engaged in anti-immigration efforts. When the Palmah members were discovered, shooting erupted. British forces arrived at Biriya, conducted a search, and eventually weapons and ammunition were found buried at a nearby quarry.

The two dozen Palmahniks were marched into Safed and locked up. They were then moved to Acre Prison, where their martial trial was opened on May 30. They were defended by Aaron Hoter-Yishai.

In the interval, the British had appropriated the stronghold. In response, taking advantage of the traditional march to Tel Hai on March 14, three thousand Zionist youth movement members from all the various groups ascended to Biriya. Defying the British, who were totally surprised, they refused to disperse. The British then demolished the buildings and evacuated the 150 who remained on by force.

Subsequently, hundreds of people from the area returned to rebuild Biriya a third time. The British Army then retreated, and eventually a Bnei Akiva group arrived, and two months later the British abandoned the fortress altogether.

At the trial, the accused addressed the proceedings with an unequivocal declaration that, indeed, the weapons discovered were in their possession, yet “these weapons are weapons for defense. When we ascended to Biriya, we were aware this is a dangerous place, and we decided we were willing to endanger our lives rather than allow our efforts to be destroyed. The defense of ourselves is a necessary method and a right of existence.”

Twenty, aged over 18, were sentenced to four years imprisonment; two, aged 17, to two years behind bars; and two, under the age of 17, received one year’s incarceration.

However, earlier in the affair, on March 9, the day following their transfer from Safed to Acre, the prisoners were ordered to provide their fingerprints. They refused, citing their status as “political” detainees rather than being “criminal.” The officer in charge, William Bruce, ordered the British investigators to force them to stretch out their hands. The prisoners were beaten, the arms twisted and some had fingers broken. Several were sat upon by the British and “ridden” around the room. In protest, a hunger strike was begun that lasted five days in mid-May.

Bruce had previously tortured Hagana prisoners at the Atlit detainee camp, and the Hagana felt that corporeal punishment was becoming an acceptable feature, heretofore reserved only for members of the Irgun and Stern Group undergrounds. The Hagana newsletter, Bamahane, published a warning, and a Hagana “court” sentenced Bruce to death.

Aware of his predicament, Bruce left the North and attempted to drop out of sight.

Yigal Allon then ordered Spector, who, at 23, commanded the Palmah’s Third Brigade, to carry out the assignment.

Eventually, Bruce was found to have been reassigned to Jerusalem.

Due to the events of June’s “Black Sabbath” and the July demolition of the Mandate government’s Secretariat offices and those of the army’s general command in the King David Hotel’s southern wing in July, the assassination was suspended but was renewed in the fall.

AS THE 34-year-old Bruce approached the Russian Compound’s rear entrance opposite Aristobulus Street at 10:45 p.m., six young men and one female stepped out of the shadows and surrounded him. Each was armed with a revolver, retrieved from a weapons cache hidden in the nearby Ticho House, and each fired two shots into him.

The Revisionist daily, Hamashkif, reported that “the wounded officer lay in the street bleeding for some time, because according to an instruction from high up, no Magen David Adom ambulance was dispatched.” Bruce died at the military hospital on Mount Scopus just an hour and a half later.

Haaretz the following morning informed its readers that Bruce was murdered in error. “It appears that the officer William Bruce’s killers did not intend to harm him, but, rather, an undercover police officer who was with Bruce until a few minutes before his murder” was the version the newspaper printed. Other reports, most probably originating in a Hagana black ops PR effort, sought to blame either the Irgun or Stern Group as being responsible for the assassination.

Two days later, on Saturday night, a night curfew was imposed on Jerusalem’s center. According to the official announcement, it was due to a “serious recrudescence of Jewish terrorist activity in the Jerusalem area during the hours of darkness,” which had resulted in “one British police inspector, two British soldiers and one British airman killed; a British colonel, two British soldiers and one British airman seriously wounded; and one Arab civilian slightly wounded.”

Spector was interviewed in 2010 by the Toldot Yisrael project which documents Israel’s 1948 generation. To Modi Snir and cameraman Peleg Levy, he said he had no regrets over his participation and would repeat the act.

Spector’s older brother Zvi led 23 Palmah saboteurs who sailed out from Haifa in 1941 on a mission in Lebanon to sabotage oil refineries. They never reached their target and were never found. They disappeared.

In an ironic family connection, Zvi Spector’s son is Brig.-Gen. (ret.) Iftach Spector, who signed the September 2003 “Pilots’ Letter” at the height of the Second Intifada. In it, 27 reserve pilots in the Israel Air Force informed their commanders that they would not take part in “illegal and immoral’’ strikes on civilian populations in the Gaza Strip and Judea and Samaria. Spector had taken part in the bombing of the Osirak nuclear reactor in Iraq in 1981.

A further irony is that for years, at the time and in the following decades, the Palmah (and Hagana) proudly proclaimed their fighters’ high moral standards, the famous “purity of arms” concept, as distinguishing them from the brutish and sordid behavior of the dissident undergrounds. Yet, in this instance, the Palmah, to warn the British not to treat its members as if they were of the Irgun and Stern Group, saw fit to behave exactly like them in order to prevent the British from continuing to physically injure their prisoners.

Moreover, the assassination was the sole Palmah operation in Jerusalem until the start of the War of Independence in late 1947.

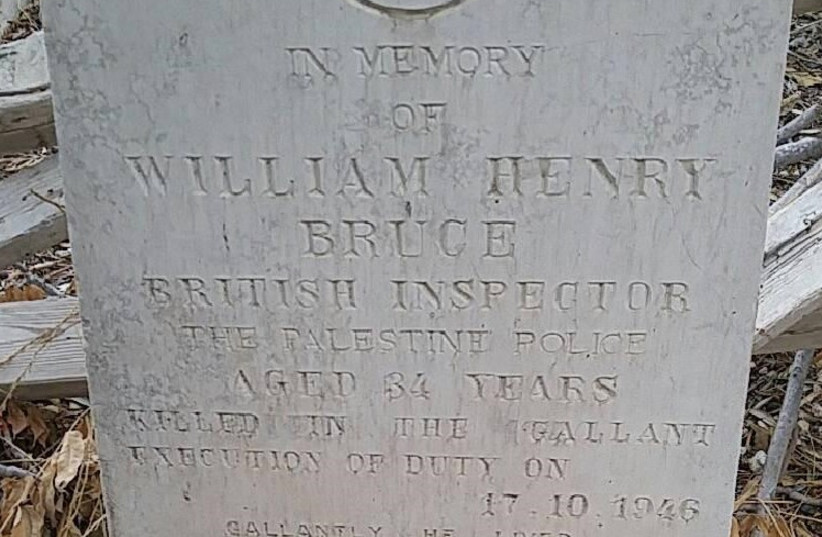

As for Bruce, he was buried in the Mount Zion Protestant Cemetery in Jerusalem with the rank of inspector of the Palestine Police. His gravestone reads: “Killed in the gallant execution of duty.... Gallantly he lived. Gallantly he died”. He was survived by his parents, who lived in London. ■