Amram – the organization that campaigns for a state apology and memorialization of thousands of babies and toddlers of families from Yemen, North Africa, the Middle East, and the Balkans, who disappeared in the 1950s – demands that the Health Ministry accept as ministry policy the 2021 report on the issue.

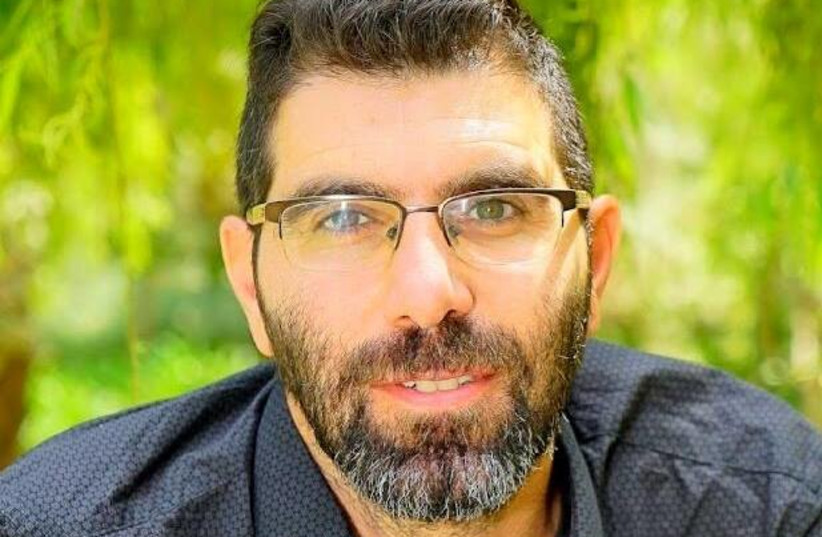

Tom Mehager, Amram’s executive director, said he had been told that Meir Bruder of the ministry’s legal department opposed publication because it would have to take legal responsibility for the consequences and could be sued.

In an interview with The Jerusalem Post, Mehager said that families of missing children have applied for less than half of the NIS 162 million budgeted by the Treasury as compensation. The main reason, he said, is that the money was an “insult” given the crimes perpetrated against the families. In addition, in some cases, there are no surviving heirs, and siblings would have to divide up a small amount of compensation.

Why did thousands of babies go missing in Israel in the 1950s?

Historical documents collected and published in books and articles by Hebrew University historian Dr. Natan Shifriss have carefully documented over years the disappearance of more than 2,400 babies and young children, some of whom were allegedly adopted, mostly by Ashkenazi Jews in Israel and abroad. At the time, according to Shifriss, the immigrant families living in tent cities were regarded as “too primitive” to raise their children, who would have a “better life” with different adoptive families. There were surely many others who haven’t complained because of no surviving parents or siblings, or have simply given up on the search for the children, Shifriss said.

Graves in several cemeteries that allegedly held the bodies of children who “died of illness” have reportedly been dug up in recent months by the authorities. In all cases this has resulted either in no remains being found, or, when bones were found, a genetic connection with the families was unable to be confirmed.

Mehager said that Amram demands not large sums of financial compensation but an apology from the state, recognition of the racist act of “stealing” babies and toddlers and claiming they were dead, and the establishment of a museum in their memory.

The chairman of the internal ministry committee that investigated and wrote the 50-page unpublished report in 2017 was epidemiology Prof. Itamar Grotto, a public health physician who has served as both the ministry’s director of Public Health Services and as the associate director-general.

Mehager said Grotto, who is now a professor at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, wanted it to be publicized. “This scandal is a social wound. It was the establishment versus a weak population,” he continued. So far, said the Amram executive director, Health Minister Moshe Arbel has not seen fit to meet with the group and hear their complaints.

Health Ministry spokeswoman Shira Solomon said: “Three health ministers and three ministry directors-general decided that it was not possible to adopt the draft report on the involvement of the medical personnel in the case of the children of Yemen, the East, and the Balkans that was brought before them. This is due to the [inadequate] quality and professionalism of the document and the notable failures arising from it in terms of research methods and methodology. The draft report was written by an undergraduate law student and edited by an internal team that did not have the tools and knowledge to conduct historical medical research.”

The decision not to adopt the report, Solomon continued, “was made, among other things, after consultation with an expert in the field of medical research who found that the document is biased and based in large part on sources and arguments that have been scientifically proven to have been taken out of their historical context and found to be unreliable.”

The spokeswoman added that Health Minister Moshe Arbel recently decided to establish a committee “to examine the involvement of the medical teams in the case, and the ministry will make available to the committee all the information it needs to examine the matter. We will continue to work to find the truth, all while discussing and fully coordinating with the families with the appropriate sensitivity on this painful issue.

The ministry did not explain why the report was “unprofessional,” given the fact that the man who headed it and wanted it published was a respected senior ministry administrator and physician for many years.

Asked to comment on the ministry statement, Mehager replied: “The ministry did not answer your questions. They are dodging it. Why are the Health Ministry’s legal department and the Finance Ministry involved?”