The hotel lobby of the Yam Suf Hotel in Eilat looks like any innocent hotel lobby – white with plenty of sunlight, large leafy plants, and summery rattan furniture.

But when night falls and the long hours stretch endlessly into the dark as they can’t sleep, this is where the 160 kibbutz members of Nir Oz who were evacuated here following the October 7 Hamas massacre gather. For now, this place has had to replace their beloved dining hall, which they reached through the tree-lined Jacaranda Boulevard path. Nestled within a spectacular botanical garden, the kibbutz boasted more than 900 varieties of trees, plants, and flowers, before Hamas terrorists burned half of it to the ground.

“We sit and cry. It is really hard to go to sleep,” said kibbutz member Irit Lahav, who survived the attack locked into her safe room together with her daughter and dog for 11 hours, using an oar and a vacuum cleaner to fashion a makeshift wedge to prevent the terrorists from opening the door which can’t be locked. “We sit here till 2-2:30 in the morning and talk about what we are going through; it is very emotional.”

At first the hotel tried to provide them with entertainment to distract them, with clowns and singers, but it wasn’t the right thing for the kibbutz members, she told The Jerusalem Post.

“For us it didn’t work. We need a lot of peace. We had so much on our minds, for us we just needed quiet. The fact that we are right next to the beach is so helpful [while] we are going through what we are going through,” she said.

The hotel has beautiful pools, but not one single person from Nir Oz has used them, she said. October 7 was to have been celebrated as the final pool day of the season at the kibbutz.

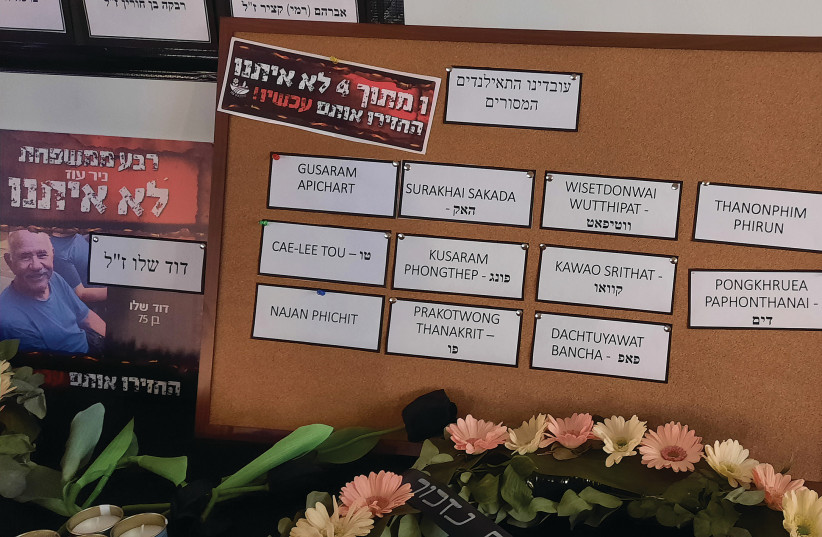

With a population of only 427 people – including foreign workers and a caretaker – Nir Oz was among the hardest hit of the kibbutzim, with one quarter of its people either murdered or taken hostage. Forty were murdered, including 11 Thai workers, and 79 kidnapped, including a Filipino caretaker and a Tanzanian agricultural worker. Half –16 – of the 31 children being held hostage in Gaza are from Nir Oz. The names of the Thai workers are included in their memorial to those killed and missing.

The kibbutz’s famous paint factory, Nirlat, was completely destroyed.

Still living a collective kibbutz life, everyone is like one big family, Lahav said.

“When I hear of people who were murdered or kidnapped, it is as if it happened to my family,” she said.

Located only 2 kilometers from the border with Gaza, the veteran kibbutz, founded in 1958, was an easy target for the marauding terrorists and looters who came in their wake, once they easily broke through fencing that was supposed to protect it. Two paved roads lead straight into Gaza, noted Lahav, providing quick and easy access in and out of Gaza. The kibbutz emergency standby squad fought off the terrorists for almost 11 hours before the army arrived, she said, and most were killed defending the kibbutz.

The members’ two main requirements when they were evacuated was that they stay together as a group, and that they be allowed to bring their pets with them, Lahav said, which the hotel allowed.

“They are very kind to us,” she said.

Eilat has doubled its population as it has absorbed some 60,000 evacuees – some from communities 4-7 km. and less from the Gaza border evacuated by the government, which provides for food and board, and others farther from the border who self-evacuated, explained Yotam Polizer, CEO of IsraAID, which has for the first time since its establishment 22 years ago started a mission helping evacuees from the Gaza border communities, and is working in seven sites in Eilat, helping each community with its needs, including providing field schools for elementary-aged children – one will soon be functioning for the 600 children of the Eshkol Regional Council at the Eilat Field School.

The Eilat and Sderot municipalities are working together to set up schools in the hotels, and the Ben-Gurion University Eilat campus is also hosting a school for students from Kibbutz Kerem Shalom and Moshav Sde Nitzan.

“We are working in close partnership with the Education Department of the Eshkol Regional Council. The schools are so important... to restore some sense of normalcy, some sense of stability in an unstable situation,” he said. So far, he said, the coordination of the schools has been in collaboration with the local councils, and not so much with the national government. “We are working with the local government of the City of Eilat. Civil society and the local government are doing an incredible effort here. We do hope the [national] government will be able to take over soon.”

IsraAID also provides parent-children spaces for children to play under professional therapeutic supervision, and for parents to relax and start healing.

“As therapists we are used to dealing with difficult situations. This is not the time to [start] therapeutic treatment but a time to contain, to help people regulate [themselves] so they can keep working. We are building on community; we are building strength rather than [giving] therapeutic treatments. Five weeks have gone by, and some people who weren’t able to talk are able to talk now. We change our responses in terms of [the developments]. It is very raw,” said art therapist Dr. Debra Kalmanowitz. “The challenge is being flexible. Even for children we can only listen and help them find strength.”

For kibbutz members the best therapy is being together, said Lahav. The trauma they share has strengthened the collective solidarity and their appreciation for one another, she said.

“When we see each other we can fall into each other’s arms and cry,” she said. “It has a hugging effect, a stronger love.”

After leaving the kibbutz 20 years ago, she returned four years ago when a new neighborhood was built, and, like many of the kibbutz area residents, was a peace activist, driving Gaza residents who were sick from Gaza to Tel Aviv hospitals for treatment two hours away.

“Most people in the kibbutz are peace lovers,” she said.

But after some 100 terrorists with heavy weapons entered the kibbutz, killing and kidnapping members, including her neighbors and best friends, Liat and Aviv Atzili, her illusions have been shattered, she said.

After the terrorists attacked, civilians came – some as young as 15 or 16, and looted her house, taking cellphones and credit cards, and even tried to make purchases with them inside Gaza only a few hours later.

“I used to think there were a few extremist people supporting Hamas, and all the others were good people who want to live peacefully.” Now, she said, she is not so sure,

The kibbutz members will stay at the hotel till the end of the month and then move to temporary private housing in Kiryat Gat for eight months, until the government completes construction of a caravan neighborhood for them near another kibbutz. They may be able to move back to Nir Oz after it is rebuilt in three years, though there are differences in opinion as to whether they even want to return.

“This terror attack is about to change completely how the southern part of Israel will be in terms of civilian life, said Renana Gome Yaakov, whose two sons, Yagil, 12, and Or, 16, Yaakov were taken hostage into Gaza.

Watch on YouTube

An 80-second animation film (https://youtu.be/c6RtxX4ON2s) by Yoni Goodman, animator of Waltzing with Bashir, tells their story. Yagil also appeared in a recent video released by Hamas, and Gome Yaakov said she was very happy to see her younger son, but she would not fall into the Hamas trap and would not comment further on the video.

“No one in their right mind would bring their child back [to live there]. Can you imagine bringing children back to the place where they were kidnapped?”

“I can’t even think about the question whether to go back to live on Nir Oz, said Eyal Barad, 40. “At the moment the answer is no. For me it is an irrelevant question.”

He had watched the attack unfold from the safe room where he was sheltering with his wife and three children – watched it live on the security camera he had installed on his porch earlier. The images show young Palestinian boys and a woman stealing bikes, terrorists on a motorcycle kidnapping his across-the-street neighbor, a young woman whom they covered up because she was wearing pajama shorts and a sleeveless T-shirt.

Miraculously, though the terrorists entered his house, his immediate family survived unscathed. “The fact I am here now is a miracle. I am still in trauma. I am still processing the event. It is like asking me if I will go swim to Turkey. The answer is no. It is not something I can even think of. I lost my trust in everything. I am not saying I want revenge; I am just saying I lost my trust.”

[During the attack] a lot of people were sending messages that they were shot; their houses were being burnt down, he said. His father-in-law was shot and slowly bled to death, dying four hours later in his mother-in-law’s arms, as no one was able to come rescue him, he said.

“Unfortunately no one was coming to help. I already understood that we were alone. There was nothing else we could do, and we were alone,” he said. “I trusted that this wouldn’t happen, that the army would defend us. I felt rage, baffled, sadness at what happened.”

Following the Hamas attack, the independent Hebrew news site Shakuf and other media accused the government of neglecting the security of the southern front in favor of the settlements. Shakuf noted that when the Foreign Affairs and Security Committee met for a confidential discussion of the war on October 10, it was the first time in the current Knesset that a committee discussion had been devoted to the southern front.

Twenty-eight-year-old Eran Similansky is thin and lean, with an intense gaze. A member of the Nir Oz standby squad, he found his house surrounded by terrorists almost as soon as the squad was called up on the morning of October 7.

He had his weapon and 30-35 bullets. He knew he would have to pick off the terrorists coming into his house one by one and use the element of surprise. First they spent two hours stealing everything he had, he said. Then they came looking for him. He had not locked the safe room door, and hid inside the closet in wait. When two terrorists opened the closet door, he quickly shot them. They were able to make their way out with the help of the other terrorists.

“I knew I had to catch them before they catch me,” he said quietly.

Six terrorists came into his house and he proceeded in a deadly game of cat and mouse, until he had shot them all.

In the meantime, he was receiving phone calls from friends begging for help, saying they were being burned alive. Similansky had to decide between remaining in his house and staying relatively safe, or risking his life to rescue his friends. He chose to rescue his friends.

“There were no police, no army. I felt like everyone had died except for me,” he said.

Once outside in the kibbutz he met his friend Benny Avital, and the two wrapped themselves in wet towels and began rescuing families from their burning homes. One hour later military reservists arrived and helped in the rescue efforts; the regular army unit arrived only 40 minutes later. The first ambulance arrived at around 5 p.m.

“I always thought the military would protect us, would guard us. It is very hard to say who to blame, but I feel like I’ve been stabbed in the back by the army and the government – we all know that the government tells the army what to do – and by the Palestinians who worked with us. I worked with hundreds of Gazan Palestinians,” said Similansky. “I understand why they hate us; the same reason why I hate them now. For the last 20 years we have fought in Gaza, bombing and killing many Gazan people, and every year we built more hate for us.”

Four terrorists were waiting for Natalie Yohanan’s husband, Shai, when he opened the front door to join the standby squad. After a 40-minute shoot-out, he called to her to open the door, and they both rushed back to the safe room, where their daughters were hiding. She kept promising her children and her French-born sister-in-law over WhatsApp that everything would be okay, that the army would arrive soon.

The last message she received from her father was “Don’t worry it will be over soon.” Ten minutes later he had been shot to death.

Shai held the safe door handle for 12 hours until the army arrived, so that the terrorists, and then the looters – including a woman who took all her jewelry, shoes, underwear, passport and makeup, and fed the male looters food from her refrigerator – wouldn’t be able to open the door. They didn’t seem to be in any rush, and got onto her Netflix account and changed it to Arabic, she said. The woman was very calm and started singing, said Natalie. Every 30 minutes they would come to knock on the door of their safe room and make feeble attempts to enter.

“We feel so humiliated and violated. They entered my sacred place, my house. They took our feeling of faith that normal people of Gaza won’t come,” she said. “I don’t want to think that these were people who knew us, who worked with us. Some of [the kibbutz] Palestinian workers called us and told us it wasn’t them. But the feeling was they know exactly who lived where; they knew the layout of the house. My belief in people was shattered.

“I thought my kibbutz was the safest place for my kids in Israel. Despite everything, we believed the army is around and they can come defend us.

“Right now, all I care about is my kids, and to get them to trust people again. I don’t want to raise them to hate; I want to raise them to love. That is the hardest part.”