Considering the numerous – possibly countless – side effects of social, sociopolitical, socioeconomic and other forms of conditioning to which we have been exposed over the generations, it is a fair bet that whenever we see a monochrome photograph or movie, we immediately slip into nostalgia mode.

That is not necessarily a bad thing, in emotional terms, as we waft away on the clouds of time. But that necessarily means we relate to the visual content in a historical context.

But what, for example, was street-level life really like in Jerusalem in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s? Of course, we can dip into any of numerous academic tomes or novels that offer some kind of portrait of the contemporary zeitgeist, but they do say a picture is worth a thousand words.

That is definitely the sense I got when I made my way over to the front side of the Clal Building to catch the exhibition currently on display at the alfresco Black Box Gallery at 97 Jaffa Rd. The Hebrew title of the show – “Yerushalayim Tofeset Tzeva” – translates as something like Jerusalem Gets Color, but curator Efrat Sinai opted for a far better English equivalent, Out of the Gray, which conveys a good sense of the transformative enterprise.

THE ORIGINAL works were imbued with glorious polychromic life by Tamar Hayardeni, whose various professional hats include researching Jerusalem’s past.

We are told that “in the last few years she has specialized in the processing, restoration and coloring of black-and-white images, as part of a process of uncovering Jerusalem’s secrets and restoring daily life there.” She has managed that with gusto with this exercise.

“I think Out of the Gray is better,” says Sinai, who spent many an hour, in the run-up to the event, sifting through thousands of prints from the Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael-Jewish National Fund archives she oversees. “You know, when you look at a color photograph, the sky is no longer gray, as it is in black-and-white pictures. It gives you a very different viewpoint on the content.”

That is core to the thinking behind the “Out of the Gray” moniker. “It is like the expression ‘out of the blue,’” Sinai laughs. “It surprises you.”

It certainly does, and illuminates into the bargain. Take, for example, an alluring scene taken at a downtown bus stop in 1950, the most recent work in the outsized print spread. There are pointers about so many areas of the quotidian urban routine at the time. We get some idea of the sartorial elegance mindset of the better-heeled back in the day. A young woman is wearing a fetching polka-dot dress, while the man next to her sports a smart blazer.

Archaeologists scrutinize finds for motifs that help them place the relic in its correct historical and cultural milieu. The aforementioned photo, taken outside the then-bus station at 46 Jaffa Rd., a hop skip and jump down the street from the Clal Building, offers plenty of signs of the commercial goings-on in the vicinity, and the mix of consumer items available in Jerusalem at the time. It is surprising to see the sign of the Glaser vegetarian restaurant. Even as a vegan, I had not contemplated the possibility of “alternative” dietary habits in the incipient Jewish state.

Sinai jokingly counters the notion that, perhaps, there were quite a few city dwellers who followed a health-conscious lifestyle.

“Maybe, but look, there’s a sign for Matossian Cigarettes right next to it,” she laughs. “That was a very popular brand back then.”

The print also suggests that Egged was not overly concerned with user-friendliness as the fledgling state struggled to its feet. “See, there’s no bench for people to sit while they wait for the bus to arrive,” Sinai adds. Indeed, and no shade either. Mollycoddling was not exactly on the sociopolitical agenda in 1950.

THERE MAY be purists who shudder at the thought of “tampering” with history, by turning monochrome documents into polychrome snapshots when, admittedly, the colors and shades of the reimagined work may not be entirely faithful to the source.

However seeing Jerusalem in, presumably, something close to what we might have caught had we been around in the days in question makes the people and places in the photos more amenable and accessible.

That applies equally to scenes of a definitively heroic nature, and the more prosaic type. The former palpably comes across in a shot of around 50 soldiers in Katamon in April 1948, in the lead-up to the declaration of the new Jewish state. There are various subtexts to the group picture, snapped by German-born Lasar Dunner, which captures the less than spick-and-span bunch shortly after they endured a particularly fierce altercation over the then wealthy Christian neighborhood of Jerusalem.

“That was taken after one of the most important battles of the entire War of Independence, the battle for San Simon,” Sinai notes, referencing the St. Simeon Monastery, at the highest spot in the area, which, at the time, served as the Arab forces’ HQ. “You could say that battle sealed the fate of Jerusalem in the war. It was a bloody battle.”

The expressions on the soldiers’ faces come through far more clearly in the color version. Some of the mostly young men look completely spent, while others are in undisguised triumphal mode, smiling widely and lifting their rifles aloft. Herein lies another slice of added value of the “Yerushalayim Tofeset Tzeva” project.

Putting the archival gems out there, in full 24/7 view of downtown passersby, in larger-than-life prints, invites public response. That can also lead to Sinai and her cohorts at the KKL-JNF Photo Archive gaining some more insight into the documental minutiae sequestered in their vaults.

“Look, there are women there, too,” Sinai exclaims. “I didn’t see them at first, but, you know, when you take a close look at every face, as Tamar did when she worked on the picture, you take in all the details.”

That was something of an eye-opener for Sinai, and there was more, on a more individual historical nature, where that came from. The archive head was eager to grasp as much background information about the subjects as she possibly could. That often meant trying to get as close to the source as possible.

“I got in touch with the son of the commander of the battle in Katamon,” she explains. “He is famous. He was called Eliyahu Sela, and was nicknamed Ra’anana.”

Therein lies another juicy folklore tidbit. Sela got his sobriquet when he was stationed with the Palmah forces at Kibbutz Kiryat Anavim. It seems there were five youngsters in the unit with the same first name there at the time, and Sela was differentiated from the rest of the pack by taking on the name of his hometown.

“I called his son, Asaf Sela, and I said to him there are quite a few people in the picture, and we must, surely, be able to discover something about some of them,” Sinai continues. “Asaf put it out in the Palmah veteran [social media] groups, and one of [the members] came back to him and said: ‘The man with the moustache is my dad.’ He also told us stories about the battle he’d heard from his father.”

The said gent is to the rear of the group, partly obscured by the rifle of one of his battle-weary but elated colleagues, with archetypal kova tembel headgear on his pate.

“His name was Yehiel Prager,” says Sinai, adding that Hayardeni’s painstaking work brought her – literally – very close-up to the yesteryear characters.

“Tamar said that, although we see a lot of them with happy expressions on their faces, she noted the beginnings of post-trauma symptoms. You can clearly see that not all of them felt a sense of joie de vivre.”

THE MORE state-oriented topics jostle for position at the gallery with scenes of a more mundane nature.

The shot of the Tipat Halav (A Drop of Milk) delivery man is a gem. Mind you, Sinai had some misgivings about the bloke’s demeanor.

“He looks a bit creepy,” she laughs.

The photograph, taken in 1927 by Zecharia Kotler – Kotler also documented numerous sites of historical importance around the country in the 1920s – bears the succinctly epexegetical caption: “On his rounds, distributing pasteurized milk to babies in the Old City of Jerusalem, 1927.”

The print also exemplifies the editing work that was undertaken along with the coloring process. All the originals are shown on the side of the display cabinets, which, by the way, are illuminated after nightfall. The 1927 print has a lot more of the Old City cobblestones in it, and the cropping does a good job in enhancing the composition.

The exhibition features the work of a slew of front-grid snappers from the 1920s-1940s, including Galicia-born, Vienna-educated photographer Joseph Schweig, who made aliyah in 1922. In the mid-1920s he earned a crust in the employ of the KKL, and he is considered largely responsible for getting the visual side of local Zionist endeavor out to the world. His inclusion in “Yerushalayim Tofeset Tzeva” is particularly apt, as he produced the first color photographs in pre-state Palestine, in his workshop on Hanevi’im Street.

Schweig, in fact, is the principal contributor to the exhibition, with four of the 10 exhibits courtesy of his polished documentary and aesthetic acumen. His ideological bent is front and center in the clearly staged 1929 shot of stonemasons, wearing what appear to be their best threads, on a building site.

The official ceremonial side of life here close to a century ago is presented in the 1931 photo, taken around Shavuot, with members of Moshav Atarot proffering “first fruits” at the KKL-JNF building at the top end of King George Avenue.

Sinai says there are several historical strata to the work. “The moshav was abandoned in 1948. And this [first fruit] custom started after KKL built National Institutions House. It was a sort of substitute for the temple. People came from all over the country to bring their first fruits there.”

Another Schweig picture features Boris Schatz, the legendary founder of the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts – the precursor to the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design – then on Shmuel Hanagid Street. The dynamics of the 1924 shot make for fascinating viewing, with a couple of open-air portrait painting classes in full flow.

The last Schweig exhibit is, possibly, the best known, as it has been put on show several times over the years. The leading members of the Ashkenazi bourgeoisie, of 1920s Jerusalem, are on display as they gathered in a somewhat rough-and-ready spot and settled down to a classical piano recital betwixt the rubble at the Tower of David.

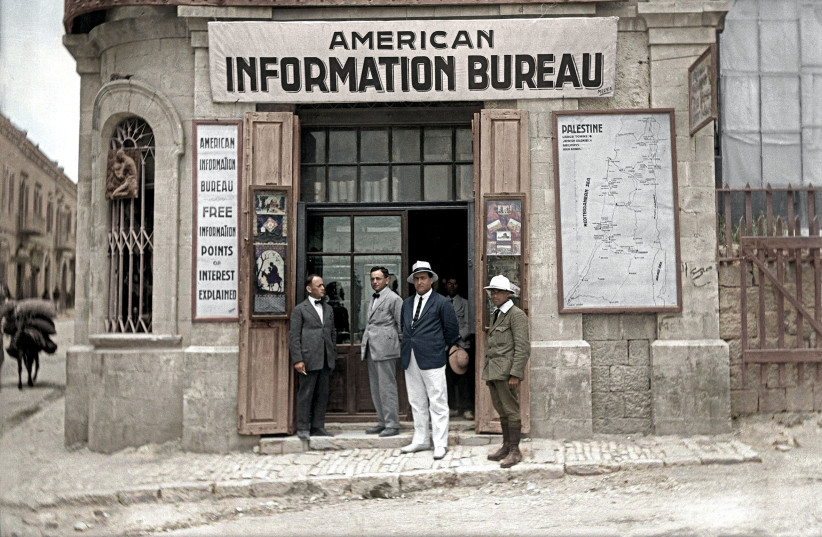

The brace by Avraham Malevsky, another important KKL-employed photographer of the 1920s-1940s, also catch the eye. Ever aware of the importance of balancing his art school’s books, Schatz established a sales booth at the then Post Square – now IDF Square – which also served as the American Information Bureau. The colorized version really brings that one to life. And Malevsky’s 1943 shot of Jerusalem offers an unexpected vista of the eastern side of the city from the Hebrew University on Mount Scopus.

With the memory of her previous KKL archives display at the gallery experiencing a bit of a rough ride, as lockdowns interrupted the exhibition flow, Sinai says she is delighted to have the archives’ new show out there in downtown Jerusalem.

“It was so labor-intensive, too,” she notes. “Tamar did a brilliant job on this. I think anyone who loves Jerusalem will be moved by this.” ❖

“Yerushalayim Tofeset Tzeva” runs through to July 15.