A lipstick-wearing robot confessed, “it was a crime to build the robots,” as she and her friends faced their certain death at the hands of rebellious machines. “Even now I do not regret making robots,” her husband said. “Work was too hard, life was too hard.’

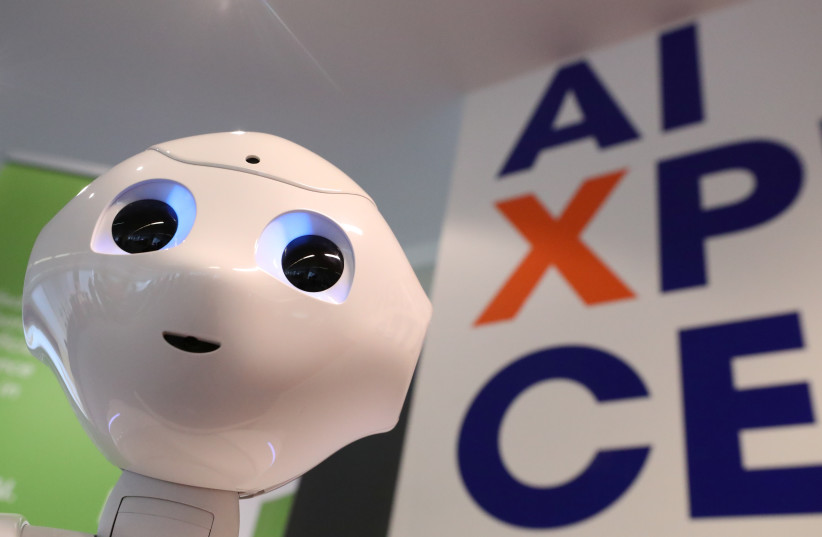

In the Jordan Valley, inside the small Beit Uri and Rami Nehostan Museum, Guy Bar Amotz has adapted Karel Capek’s 1920 play R.U.R, a science fiction classic, for his exhibition The Revolting Robots Show (curated by Smadar Keren). He was also inspired by circumcision, the Golem and British rock.

R.U.R coined the term “robot” and became such a global hit that Avraham Shlonsky translated it to Hebrew when Ohel Theater produced it here in 1930. The play wondered what differences, if any, separated humans from machines and suggested humanity does not have a moral right to create androids just to bend them to its interests.

Bar Amotz focused on a key scene in the play, that of the robot uprising. The full play goes on beyond that point to suggest a future when machines mimic their slain human masters in one capacity, longing to love and reproduce.

The work is delightful. As in his 2014 Ein Harod exhibition me-you-collaborators (curated by Galia Bar Or), where he placed the voice of an art critic inside a garbage bag, Bar Amotz insisted on showing the viewer how the magic is done.

The result is a combination of low tech and high tech.

The large figures move in relation to a projection of a short film, which pushes the plot forward. The intense music, lights and the fusion of actual movement in space with virtual characters on screen made the work into a highly entertaining apocalypse.

When the machines began their rampage, the lights went off and we saw another part of the exhibition move. Large paper sketches with words written on them began to change positions. Then The Dickheads began their own performance. These are three mechanical musicians with large male organs mounted on their heads. Like the first part of the exhibition, their real-space movements are in relation to the video interviews they offer. The absurdity of watching such a machine chew a carrot like Bugs Bunny and discuss “golem servants” made from “Jewish soil” is hilarious.

Made from clay and powered by the divine name of God to defend Jewish lives, the legend of the golem was also employed by Yael Toren in her 2016 work Pieta, which showed a multitude of clay golems, each carrying a slain protector, as they march across the plains to an unknown destination. The animated art-video was shown at the same museum during the Women Workers’ Movement group exhibition, likewise curated by Keren.

At that time, Keren was just beginning her mission at the museum, having taken the reins from previous curator and manager Ruth Shadmon.

A kibbutz member, Shadmon worked hard and kept the doors of the museum open for more than a quarter of a century under very difficult financial conditions. In this, she was aided by curator Tali Tamir and others. In 1990, the museum hosted a solo exhibition by Siona Shimshi titled Aching Head and Hallucinations. Several of her works, as well as works by Igael Tumarkin and David Fine, can be seen at the museum’s garden today.

Expertly managing the museum’s small team of dedicated workers, Keren moved from Tel Aviv to nearby Afikim in 2017 to turn the museum into a contemporary art space serving the Jordan Valley.

One success was the 2018 group exhibition The Magic Kingdom (curated by Avi Lubin), which included the performance installation “Buddy / No Body Holy & the Crickets” by Oree Holban.

Like Bar Amotz, Holban skillfully used a pre-known tale, that of the artificial Pinocchio wishing to become a real boy, but introduced other themes: self-acceptance and transgender perspectives.

In R.U.R, Capek tied the conquest of labor by working machines to human bodies becoming superfluous. As people no longer knew what their bodies were good for, they could not bring new life into the world. The robots, after killing their masters, were faced with extinction as they, too, did not know the secret of birth.

The bodies of working men and women were celebrated at the museum in the 2021 exhibition Place, Architect, Artist (curated by Michael Jacobson), which honored the public artworks once proudly commissioned and displayed across this land. Murals by Sheldon Schoneberg lauded the body of the Jewish man of the field and depicted him as a direct descendant of the ancient Near-East harvester of wheat (at Kibbutz Afikim). Haifa’s Dagon granaries boast a graffito by Mordechai Gumpel, in it a barefoot woman proudly squats, facing the viewer, with kernels held between her legs.

The museum seems keen to present excellent art and utilize its power to tell tales about our human bodies in this land. Women Workers’ Movement also includes the neon work by Nelly Agassi “Is this the hill I’m going to die on.” In his When Spring Falls Asleep (curated by Tali Ben-Nun, now being shown at the museum) Uri Weinstein presents a 10-minute video titled “Tsalafim.” The Hebrew word means both snipers and capers. The algorithm floods the viewer’s eye with images of telescopic-sights, first-person shooter video games and pickled capers. The AI is smart, and dumb, at the same time. The video-loop runs on a laptop next to a smiling cap, a baseball cap with a torn smiley on it, with many candle caps strewn on the floor leading to the table. These are scalp-like wax objects with a wick that the viewer might see as candles.

One brilliant work by Weinstein is easy to miss, a mobile phone keeps vibrating near one wall of the exhibition with the word “DAD” flashing on its screen.

Titled “Incoming Call from Dad,” it is a chilling work, a punch to the gut when we consider the museum came into being by parents (Meir and Reaya) who wished to honor the memory of their two fallen sons, one of whom died in combat during the 1948 War of Independence. The work is an unanswered call by a parent placed inside such a call turned into a building.

After the terrific colorful performance by Bar Amotz’s robots, stepping into Weinstein’s space is like jumping into a pool filled with ice water.

The final exhibition on offer at the museum is Yashin by Noa Schwartz. In her 2017 work “Euro,” Schwartz created the symbol of the EU currency in a wall by carving a semi-circle into it and installing two wooden shelves. One of the shelves had a ruby carefully placed on it.

In this exhibition she presents us with “Untitled (Sink with Pearl),” which offers – a pearl. Her delicate, handsome works are often a consideration of objects human bodies need (sinks, keys) or must offer to enjoy the basic comforts of life (some works are made from ground-up electric and utility bills).

While her works are a far cry from killer-robots, Schwartz is a highly intelligent artist, and her wry depictions of domesticity and money might be the bitter pill the hi-tech nation needs.

Guy Bar Amotz’s The Revolting Robots Show is on display until July 23 alongside When Spring Falls by Uri Weinstein and Yashin by Noa Schwartz. https://www.uri-rami-museum.co.il/