For two thousand years, “the Jews” have been falsely blamed for the murder of Jesus. This charge of deicide is the oldest and most damaging and pernicious of all the “blood libels” spread to provoke hatred and killing of innocent Jews by Christians through the ages.

But a careful reading of the Christian Bible, the “New Testament,” shows that it was not the Jews but the Romans who killed Jesus. Indeed, Jesus, his family, disciples, followers and supporters were Jews, and they, like him, were the victims of the Romans, not the perpetrators.

Jesus was a faithful Jew

Jesus’ devotion to Judaism is indisputable. According to the New Testament, especially the Gospel of Mark, Jesus, his family, and virtually all of his followers and disciples at the time were Jews, as probably were the writers of three of the gospels.

Even Paul, the foremost proponent and founder of Christianity, was by his own account Jewish, “circumcised on the eighth day, a member of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews; as to the law, a Pharisee.” (Philippians 3:5).

Jesus claimed to be faithful to the laws and teachings of Moses and the Hebrew prophets, and the early “Christians” considered themselves to be Jewish. Jesus and his disciples were devout Jews, keeping kosher, observing the Sabbath, fasts and festivals (the Last Supper was a Passover Seder), saying morning prayers, and preaching the laws of the Torah. Jesus’ disciples called him “rabbi” (“teacher”).

Jesus repeatedly made it clear that he did not want to start a new religion, saying, “Think not that I am come to destroy the law or the prophets. I am not come to destroy, but to fulfill.” (Matthew 5:17).

Jesus’ words purportedly attacking “the Jews” (quoted by writers who never met him) are actually criticisms of the Jewish leadership. He considered the Pharisees (rabbis) of his day to be corrupt, self-righteous, arrogant, and hypocritical, teaching a form of Judaism based on literal law, formalism, ritual, and devoid of spiritualism and compassion.

Jesus preached almost exclusively to the Jews, who supported, dined and walked with him. Jesus stated that his mission was for the Jews only, saying, “I am not sent except to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.” (Matthew 15:24), and sending his 12 disciples out with the admonition, “Go not into the way of the Gentiles …But go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (10:4-6).

The Book of John tells us that Jesus even attended a Hanukkah party in Jerusalem (10:22), celebrating “the feast of the dedication” (of the Temple). There, he lectured and argued with the guests, reiterating his complete faith in the Jewish Bible, and saying the words cannot be changed or violated: “Scripture cannot be broken.” (10:35).

Popularity with the Jews

Jesus was very popular with his fellow Jews, the “masses” and crowds of people mentioned throughout the Gospels who revered him, followed him on his travels, gathered by the thousands to hear him speak, and protected him from the rulers who collaborated with the Romans. Luke 23:27 describes how Jesus was led away to be crucified, “and there followed him a great company of people, and of women, which also bewailed and lamented him...”

As an observant Jew, Jesus had traveled to Jerusalem for the Passover celebrations, where, upon entering the city crowded with fellow Jewish visitors, he received a hero’s welcome. Matthew 8:1-13 tells us, “When he came down from the mountain, great crowds followed him...”

It was in large part his popularity with the Jewish people that caused Jesus to be killed by the ruling Roman authorities (with the coerced cooperation of their clique of appointed Jewish agents and collaborators).

Indeed, Jesus was so popular with the Jewish people that the authorities were afraid to arrest him during Passover. As Mark 14:1-2 makes clear, “It was now two days before the Passover and the Feast of Unleavened Bread. And the chief priests and the scribes were seeking how to arrest him by stealth, and kill him; for they said, ‘Not during the feast, lest there be a tumult of the people.’” Mark 12: 12 states, “And they tried to arrest him, but feared the multitude...”

So rather than the Jewish people wanting to kill Jesus, they actually protected him from the authorities who collaborated with the Romans.

As Jesus is being led away to be crucified, Luke 23:27 refers to the “great number of people” who were following him, and in the next verse, Jesus speaks to the Jewish women in the group, calling them “daughters of Zion.” And it was Jews who took Jesus off the cross, prepared him for “burial,” mourned him – and then got the blame for the crime.

The Jewish mobs

But what about the howling, bloodthirsty mob calling for Jesus’ death that is described in the Gospels, supposedly representing the Jewish people? How could this be, since all four of these books agree that just five days before the trial, huge, friendly crowds greeted Jesus as he entered Jerusalem.

By this time, Jesus had become renowned in Galilee as a healer, a preacher, and an exorcist who might even be the Messiah, who would throw off the yoke of Roman rule. The Gospels note that the people surrounding and supporting Jesus, all of whom were Jews, were so numerous and enthusiastic that the chief priests (all privileged agents of Rome) were afraid to arrest him.

Thus, ironically, Jesus was killed because the masses of Jews loved, not hated, him.

Yet the New Testament’s inconsistent account of the supposed Jewish mobs calling for Jesus’ death grows more vicious with each chapter. Mark 15: 8-11 speaks of “the multitude” and “the people.” Matthew 27:25 refers to “all the people”; Luke 23: 1-2 states that “the whole multitude of them arose and led him to Pilate, and the began to accuse him...” In the book of John (chapters 18, 19), it is “the Jews” who are demanding that Jesus be put to death.

The Jewish collaborators with the Romans

Yes, a small group of Jewish priests and other collaborators in the ruling classes, led by the high priest Caiaphas, are purported to have urged the Romans on, and even tried Jesus (in the dead of the night on the eve of Passover, already, which would have been illegal under Jewish law !). But in their relations with the Romans, the Jews and their leaders had no real political power.

Moreover, the Jewish leadership realized that if they did not deal with this “troublemaker” and his adherents, the Romans would do so in a much more brutal fashion, as they had done years before, killing thousands in an earlier Passover riot. John (11:47-50) quotes the priests as understandably worried that the fate of the Jewish people might be at stake.

“If we let him thus alone,” they say, “the Romans shall come and take away both our place and our nation,” to which Caiaphas replies, “It is expedient for us that one man should die for the people, and that the whole nation perish not.” Such fears were not far-fetched, indeed they were realized 35 years later, when the Romans responded to a Jewish rebellion by destroying the state.

Interestingly, Luke 7: 1-10 portrays the Jewish leadership not as opposed to Jesus but as seeking his help: “And when he [the Roman centurion] heard of Jesus, he sent unto him the elders of the Jews, beseeching him that he would come and heal his servant. And when they came to Jesus, they besought him instantly...”

Later, Luke (9:22) has Jesus blaming the Jewish leadership, not the people, for his imminent crucifixion: “The Son of man must suffer many things, and be rejected by the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and on the third day be raised.”

The Romans’ brutal role

During Jesus’ time, the Romans and their governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate, ruled the country with an iron fist, and were responsible for appointing Caiaphas to his post. All accounts make it clear that it was Romans who cruelly killed Jesus – whipping and torturing him, ripping and tearing his flesh, putting a crown of thorns on his head, spitting on him, nailing him to the cross, crucifying him, even running him through with a spear.

Pilate himself even “scourged” (whipped or lashed) Jesus. He first “washed his hands before the multitude, saying ‘I am innocent of the blood of this just person…’”, and then “scourged Jesus” before “delivering him to be crucified.” (Mark 15:15; Matthew 27:26).

Thusly do the Gospels describe how the Romans dealt with this popular Jewish reformer with a huge Jewish following, “The King of the Jews,” whom they saw as a threat to Roman law and order, and to the privileged position of their collaborators in the priesthood.

It is hardly conceivable that an unruly Jewish mob could have intimidated the powerful, tough, blood-thirsty Roman ruler Pontius Pilate, who is amazingly portrayed as weak, compassionate, and malleable, “the more afraid” (John 19:8), even eager to free Jesus.

It is even more inconceivable that the Jewish “mob” could have pressured Pilate to release Barabbas, who had participated in a revolt against the Romans and even “committed murder in the insurrection” (Mark 15:7).

Pilate himself admits in John 19:10 that he has the power to kill or set free Jesus: “Pilate therefore said to him, ‘You will not speak to me? Do you not know that I have power to release you, and power to crucify you?’”

Eventually, Pilate’s brutality (even referred to by Luke) became so notorious that the emperor himself in the year 36 recalled his procurator back to Rome, after he slaughtered several thousand Samaritans on their holy mountain to disperse a crowd gathered around one of their prophets.

Accounts of Pilate’s reign of terror in Judea appear in the works of the Roman historians Tacitus and Josephus. The Jewish king, King Herod Agrippa I, who ruled from 37-44, wrote to the Roman Emperor Caligula, describing Pilate’s acts of violence, plundering... and continual murder of persons untried and uncondemned, and his never-ending and unbelievable cruelties, gratuitous and most grievous inhumanity.”

Jesus was just one of the estimated 250,000 Jews crucified by the Romans. After executing him, the Romans went on to kill his closest disciples Peter and Paul, along with countless other Jewish “Christians.” They eventually killed or expelled from the region almost all of Jesus’ fellow Jews, following the Jewish revolts of around 70 and 135 CE. This set the stage for 1,900 years of Jewish dispersal, suffering and persecution, and for the violence and territorial disputes that plague the Holy Land today.

The historical evidence

The only comprehensive historical source on this subject is the Christian Bible, mainly the books referred to as the Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, whose authors never knew or heard Jesus). Fragmentary accounts also appear in the book of Acts, and works of the Jewish historian Josephus and several Roman historians such as Tacitus.

Passages in the New Testament whitewashing the dominant role of the Romans in the murder of Jesus, which for centuries have been used to stir up hatred for Jesus’ own people, are traditionally believed to have been written 60 to 100 years after Jesus’ death. Thus the authors – whoever they may have been – did not witness the events they describe, give different accounts of them, and may have been subjected to heavy editing prior to “publication,” at a time when the church was reaching out to gentiles and attempting to discredit traditional Judaism.

The original manuscripts of the books of the Christian Bible were written in Greek, and for 15 centuries were copied by hand by scribes, whose accuracy and objectivity cannot today be determined. But we can be certain that they were subject to political and religious pressures, as well as personal and cultural biases. It is thus hard to know the exact wording and meaning of the original texts, especially after they have been translated into various languages.

There were other compelling reasons at the time for minimizing the culpability of the Romans in persecuting Jesus and his mainly Jewish followers. It might have been impossible, indeed suicidal, to try to publish and distribute, under harsh Roman rule, books that were critical of, and might incite opposition to, Rome. Better to blame “the Jews,” Jesus’ own people and supporters, even though they were victims of Roman persecution and murder.

This is obviously the reason the mob is quoted by Matthew (27:25), incredibly, as cursing itself in generational self-incrimination, “Let his blood be on us, and on our children,” the only place this statement occurs in the Bible.

In the unlikely event a mob of Jews did call for Jesus to be killed, it would have been composed of a small group of collaborators with the Romans, perhaps acting out a script written by the Romans.

This passage may also be a reference to Exodus 24:8, in which “Moses took the blood [of the sacrificed oxen], and sprinkled it on the people, and said, Behold the blood of the covenant, which the LORD hath made with you concerning all these words [of the Book of the Covenant].” This would imply that the writer felt that the mob considered Jesus to have been sacrificed to atone for their sins.

This theme is repeated in Hebrews 9:19-22, which states that “Moses…took the blood of calves and goats... and sprinkled on both the book and all the people...And almost all things are by the law purged with blood; and without shedding with blood is no remission.”

The Gospels differ significantly in other aspects as well. Only Matthew and Mark have the Jewish priests mocking Jesus, while only Luke and John have Pilate insisting that Jesus committed no crime.

In reality, the early Christians and their Gospels could not have openly blamed the ruling Romans for the killing of Jesus (and without his crucifixion, of course, there would be no Christianity!).

But today there is no excuse for perpetuating these blood libels, which for two millennia have caused Jesus’ descendants to suffer such hatred and persecution.

Yet such slanders continue to be prominently featured, such as in Mel Gibson’s movie, The Passion of the Christ, and even in reviews of it in The New York Times. Most ironic of all, a few years ago, La Stampa, one of the largest newspapers in Italy – the nation of the people responsible for Jesus’ death – ran a front-page anti-Israeli cartoon showing an Israeli tank marked by a Star of David rolling up to Jesus’ manger, with the infant crouching and crying out, “Oh, no, they want to kill me again.”

To continue to blame “the Jews” is not only false and malicious, it is a betrayal of Jesus and his followers.

Until 1965, it was official Catholic doctrine that Jews bore collective guilt for killing Jesus. For centuries, this and other anti-Jewish smears have appeared in the writings of some of the most famous and revered Christian writers, especially Martin Luther (the founder of the Protestant Church), Saint Augustine, and Thomas Aquinas.

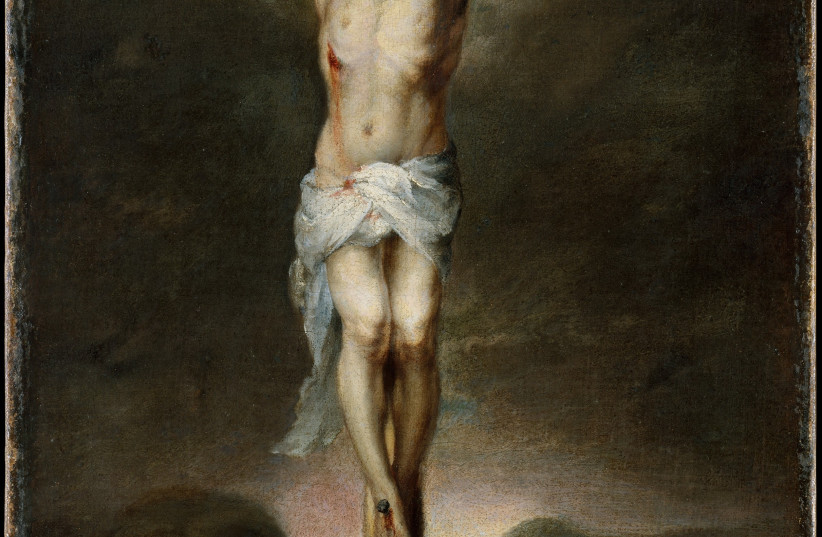

Some of the most famous portraits of Jesus’ crucifixion have depicted Jews as the sadistic perpetrators. As Menachem Wecker observes in Mosaic magazine: “In paintings of the crucifixion, Jews have usually been depicted, in demonizing detail, in the act of leering at Jesus on the cross or torturing him during the passion. Hieronymus Bosch’s Ecce Homo (c. 1475) shows a particularly fierce mob with torches and spears – the figures have hooked noses and angry expressions – reaching toward Jesus on a platform. Stereotypical-looking Jews surface in Jan van Eyck’s Crucifixion (c. 1440-41) and in Venetian paintings like Jacopo Bellini’s Crucifixion (1450) and Titian’s Ecce Homo (1543). The trope is very nearly a cliché.”

The Catholic Church has belatedly partially recognized the harm this historical falsehood has caused through the centuries, when Pope Paul VI issued the landmark document, Nostra Aetate (Latin: In Our Time), on October 28, 1965. The declaration by the Second Vatican Council on the relation of the Church with non-Christian religions said that Jesus’ death “cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today. The Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures.”

What every Jew should know

While Jews and Christians may disagree about Jesus’ divinity and whether he was the messiah, Jesus himself would have been shocked at the falsehoods and persecution to which his own people have been subjected. These lies, to which most Jews know not how to respond, have led over the centuries, even up to the present time, to widespread hatred and massive persecution and killing of Jews.

Jesus’ crucifixion is a subject that comes up some time in the life of every Jew. We should be able to defend ourselves against this blood libel, and the most effective response is to cite the story told in the New Testament – chapter and verse, as they say.

Rather than ignoring Jesus, every one of us should be familiar with the truth of his killing and teach it to our children. Finally, Christians should be aware that, whoever killed Jesus, if this tragedy had not happened they would have neither their religion nor their Salvation.”

A version of this article was first published in The Jewish Georgian. Lewis Regenstein is a writer in Atlanta, Georgia. Regenstein@mindspring.com