The High Holy Days have come and gone, and the Jewish people are now preparing to celebrate Hanukkah. But those who cannot resist another reason for a celebration might want to add to the Jewish holiday season Talk Like a Pirate Day, which was marked on September 19.

Among the notable, if poorly documented, Jewish pirates was Yaakov Koriel, a 16th-century buccaneer who commanded three ships in the Caribbean flying the Jolly Roger. Repenting, he retired to Safed, where he studied mysticism under Kabbalist Isaac Luria. Koriel is buried near the Ari’s grave in the Upper Galilee town’s Old Cemetery.

Equally obscure was Moses Cohen Henriques, whose name attests to his family’s Portuguese origins. Like Koriel, his place of birth, as well as the dates of his birth and death, are unknown. What is documented is that Henriques, together with Dutch folk hero Admiral Piet Pieterszoon Hein, captured a Spanish treasure fleet off Cuba’s Bay of Matanzas in 1628. The booty of gold and silver bullion amounted to a staggering 11,509,524 guilders, worth around $1 billion in today’s currency. It was the Dutch West Indies Company’s greatest heist in the Caribbean.

A pirate named David Abrabanel, evidently from the same family as the illustrious Sephardi rabbinic dynasty (which included Don Isaac Abrabanel, who fled Spain in 1492 after trying to bribe monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella to rescind their catastrophic expulsion decree), joined British privateers after his family was butchered by Spanish sailors off the South American coast. He used the nom de guerre “Captain Davis” and commanded his own pirate vessel named The Jerusalem.

These Jews most frequently attacked Spanish and Portuguese ships – payback for the property confiscations and torture of their brethren perpetrated by the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, more popularly known as the Spanish Inquisition. Koriel, Henrigues and Abrabanel spoke Ladino and knew the sting of the antisemitic slur Marrano, meaning “pig.”

Jean Lafitte, the most infamous American Jewish freebooter, spoke French and knew the insult of maudit juif (“damn Jew”). A US national park in Louisiana proudly bears his name. According to Edward Kritzler’s book Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean, the kosher swashbuckler was the inspiration for Johnny Depp in the Pirates of the Caribbean movies. Lafitte became an American hero after the British tried to recruit him to guide their troops through the bayou to ambush the Yankees during the War of 1812. Instead, Lafitte showed Gen. “Old Hickory” Jackson Britain’s battle plans to attack New Orleans.

The story of how in 1654, some 23 Jews escaping religious persecution came to New Amsterdam – what is today New York City – is well known. In a harrowing seven-month voyage, the Sephardi refugees fleeing the Portuguese Inquisition sailed north, docking at different ports and ultimately anchoring at the Dutch colony at the mouth of the Hudson River. The refugees had escaped from Recife, Brazil, after the Portuguese recaptured their South American outpost – which the Netherlands had seized in 1630.

Yet in 1645, according to Dutch historian Franz Leonard Schalkwijk, there were 1,630 Portuguese – (in those days, the term was synonymous with Jews) – living in Recife, a number equal to the Jewish population of Amsterdam at the time.

Where did the other refugees flee to?

Some returned to Amsterdam, including Isaac Aboab de Fonseca, the first American rabbi; and Moses de Aguilar, the first American cantor. Others disembarked at the nearby Dutch Caribbean colony of Curaçao. A less well-known fact is that some of the escaping Jews sought shelter in Jamaica.

Not Jamaica in Queens, New York, but the luscious Caribbean island that was then home to several hundred Jews and Bnei Anusim (the descendants of Spanish and Portuguese Jews who converted to Roman Catholicism under compulsion). Jamaica at the time was an anomaly in the New World. While the continents of North and South America were being carved up among the crowns of Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, Sweden and Denmark, Jamaica was a private fiefdom awarded in perpetuity to Christopher Columbus and his heirs in 1494 by Spain’s King Ferdinand. Whether the explorer was himself a crypto-Jew is an unresolved historical issue. But the Columbus kin kept their privately held domain free of the clutches of Spain’s inquisitors.

Jamaica was only one among the many remote and distant locales in the New World where Jews and apostates sought a haven far from the rapacious inquisitors of Spain and Portugal.

In 1501, the Spanish Crown first published an edict that “Moors, Jews, heretics, reconciliados (repentants – those who returned to the church), and New Christians are not allowed to go to the Indies.” Yet in 1508, the bishop of Cuba reported, “practically every ship (arriving in Havana) is filled with Hebrews and New Christians.” Such decrees banning them, followed by letters home complaining of their continued arrival, were a regular occurrence.

“Conversos with the aptitude and capital to develop colonial trade, comfortable in a Hispanic society, yet seeking to put distance between themselves and the homeland of the Inquisition, made their way to the New World. No licenses were required for the crew of a ship, and as many were owned by conversos, they signed on as sailors and jumped ship. Servants also didn’t need a license or exit visa, so that a Jew who obtained one by whatever means could take others along as household staff,” writes Kritzler.

In 1655, one year after the Jewish refugees from Dutch Brazil arrived in Jamaica, the Columbus family’s poorly defended private island was seized by Britain, Leading the armada was Admiral William Penn, the father of William Penn, Jr., who subsequently founded Pennsylvania. Under British rule, religious freedom flourished. By 1720, an estimated 20 percent of residents of Kingston were descendants of Spanish-Portuguese Jews. (The town of Port Royal, founded in 1518 and infamous for its immorality as a pirate base which had one tavern for every 10 residents, was destroyed in 1692 by an earthquake and tsunami.)

As elsewhere in the New World, Jamaica’s Jews sought economic opportunities. Some built sugarcane plantations. Others traded various commodities, including African slaves. Apart from plantation owners, Jews were allowed only two slaves.

The Jamaican community had strong commercial ties with Jewish businessmen in Europe including London, Bayonne and Bordeaux. Trade developed with Britain’s main American colonial ports, such as New York, Newport, Charleston and Savannah. But some Jamaican Jews turned to a more adventurous – and dangerous – life at sea. Captaining ships bearing suggestive names like the Queen Esther, the Prophet Samuel, and the Shield of Abraham, Jewish sailors began roaming the Caribbean in search of riches, sometimes obtained under questionable legal circumstances.

While pirates and buccaneers were outcasts and lawbreakers who attacked shipping, raided towns, and robbed people of their money and sometimes their lives, privateers were a legal version of the same. Mercenaries armed with a letter of marque and reprisal from their government permitting the attack of enemy ports and shipping during military conflict, they engaged in economic warfare – and turned over a portion of their booty to their king. In peacetime, they continued their plunder but flew the Jolly Roger in lieu of the Union Jack or the flag of free Holland.

Being either a criminal or a patriot depended on the latest developments in Europe’s frequent wars of accession and territorial aggrandizement and their concomitant battles on the colonial front and the high seas.

TO UNDERSTAND Koriel, Henriques, Abrabanel, Lafitte and the Caribbean’s other Jewish pirates, it’s helpful to examine the legacy of the better-known, if notorious, privateer Henry Morgan. He was knighted in 1674 by England’s King Charles II in appreciation for the colorful sea captain’s bravery – and the economic havoc he wreaked on Spain’s empire in the New World.

Alexandre (or John) Esquemeling joined Morgan’s band of privateers as a ship’s doctor in the late 1660s. Much of what is known about Morgan’s exploits comes from Esquemeling’s account De Americaensche Zee-Roovers (The American Buccaneers), published in Amsterdam in 1678. Perhaps hoping to sell more books, Esquemeling exaggerated his depiction of Morgan as a bloodthirsty marauder. Morgan was so outraged by his biographer’s claim that the British privateer used priests and nuns as human shields in the sacking of the Spanish colony of Portobello, that he sued the writer’s publisher. In turn, the publisher issued a retraction, saying he no longer accepted Esquemeling’s violence-filled narrative as truthful.

Esquemeling’s book became a bestseller across much of Europe and the Americas and was translated into several languages. Six years later, in 1684, his publishing hit was followed by Philip Ayres’ equally evocative The Voyages and Adventures of Captain Barth, Sharp and Others in the South Sea. This was followed by Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, first published in 1724, and reprinted due to popularity in 1725 and 1726. Many scholars now believe that Johnson was, in fact, a pseudonym of the English writer and political activist Daniel Defoe (ca. 1660–1731), best known for his sea adventure novel Robinson Crusoe.

Even as Europe and its colonies were waking up to the danger of piracy and beginning to prohibit it, the fanciful books established Caribbean pirates as a cultural phenomenon. Thus 200 years later, in 1881, a baseball team in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the new sport of baseball sweeping the United States, would take the name “Pirates.”

But thanks to Tinseltown and schlock culture, Morgan and the Caribbean pirates have become pop culture icons.

Historian Debbie Adams calls Esquemeling’s exaggerated account a partly “imaginary collection that endured.” Yet in spite of its failings, she adds, it gave rise to numerous “legends and myths of Hollywood and pulp fiction.”

By “pulp fiction,” Adams means accounts low in artistic quality but high in entertainment value. They have come to include poems, novels, movies and video games. The kitsch includes Royal Doulton china mugs depicting Morgan. The most famous novel based on his life is Rafael Sabatini’s 1922 bestseller Captain Blood. The real Morgan would no doubt have liked Sabatini. That’s because the novelist depicted him as a decent, brave and likable person.

That romantic vision of a good man fighting for justice carried over into a number of so-called “pirate” movies. One of the first was the 1935 film Captain Blood. It starred another legend in his own time, Hollywood heartthrob Errol Flynn.

Hollywood churned out a series of action movies featuring Henry Morgan or characters inspired by him. The Black Swan (1942) had a subplot about him during the time he was an English official in Jamaica. Morgan was also a character in Blackbeard the Pirate (1952); Morgan the Pirate (1961); and Pirates of Tortuga (1961). The tradition continues with Johnny Depp, as mentioned, in the more recent film series of Pirates of the Caribbean.

In 1967, Disneyland opened its Pirates of the Caribbean ride at its flagship amusement park in Anaheim, California. It was the last attraction which Walt Disney supervised before his death. The attraction helped further raise pirates’ curious appeal. Thus in 1976, the new Tampa Bay franchise in the US National Football League called itself the “Buccaneers.”

Rounding out Morgan’s latter day fame is the brand of alcohol named for him. Canada’s Seagram’s distillery introduced its Captain Morgan’s Rum in 1945. Images of the handsome privateer have become pop icons.

BUT WHAT does all this have to do with Jamaica’s Jewish pirates? Follow the trail of the pieces of eight, matey!

In 2009, the International Survey of Jewish Monuments (ISJM), which for several years had been documenting Jamaica’s historic Jewish cemeteries with the Caribbean Volunteer Expeditions, issued a report about Kingston’s Hunt’s Bay and Orange Street Jewish cemeteries. The document was released in Kingston during a five-day conference on Jewish Caribbean history that drew 200 academics, genealogists and history buffs from Oregon to Israel.

The Hunt’s Bay Cemetery, also spelled Hunts Bay – Jamaica’s oldest graveyard – was the burial ground for the Jews of Port Royal. The deceased, who lived across the harbor where the high water table of the peninsula prevented burial, were rowed to their final resting place. The earliest of the remaining 360 tombstones there dates to 1672, and its latest is from the mid-19th century. Many markers were destroyed or looted for construction over time.

The newer Orange Street Cemetery, located near the historic Sha’arei Shalom Synagogue, contains grave markers from the early 19th century. By the end of that century, Jamaica had six synagogues and around 2,000 Jews. The cemetery is still in use by Jamaica’s contemporary Jewish community, whose numbers have shrunk to around 200 people due to assimilation, intermarriage and emigration. The cemetery is located in Kingston’s newer, northern end. Previous to the establishment of the Orange Street Cemetery, Jamaica’s Sephardim buried their dead in the no longer extant Old Kingston Jewish Cemetery downtown. The 18th-century gravestones from the Old Kingston Jewish Cemetery were transferred to the Orange Street Cemetery when the former was closed due to the growing city’s sanitation laws. Placed along the north and east cemetery walls, many were partially covered by subsequent burials.

The inventory of the Hunt’s Bay Cemetery’s limestone and marble grave markers, with their Portuguese, Hebrew and English epitaphs, included some 50 bearing skulls and crossbones.

Before one could say “buried treasure,” the Jamaican government’s Ministry of Tourism realized the potential bonanza of Jewish tourists.

The ISJM report, which did not highlight the skull and crossbones imagery, was followed by a 2009 article in the Wall Street Journal. Citing “ferocious” competition from Mexico, Jamaican tourism director John Lynch said that his island country values every single visitor. Conceding that Jamaica’s Jewish history has “been a well-kept secret,” Lynch launched a tourism package that included visits to the historic Jewish cemeteries, prayers at the island’s remaining synagogue – built in 1911 by the United Congregation of Israelites with its distinctive sand floor, and a kiddush with Jewish families. Since most of the island’s Jewish sites are near Kingston, the strategy of developing the city as a Jewish heritage cultural destination fit the government’s desire to boost tourism in the scruffy, crime- and ganja-ridden capital, which most vacationers give a wide berth.

But what of the skull and crossbones on the tombstones?

Jamaica’s Ainsley Henriques – no relation of Moses Cohen Henriques – believes the tombstones with carvings of skull and crossbones likely belonged to “licensed maritime terrorists.” That interpretation strikes this writer as improbable.

A more nuanced understanding is found at the Mainblogspot:

“I know that pirates are positively charming. I mean, who doesn’t love pirates? They had parrots. They said ‘Yaaarr.’ Still, I’m not a huge fan of marauding and murder, so I was thinking that perhaps no evidence was shown that these graves are the graves of pirates. Thus, we also don’t have to ask why the Jews buried them in regular graves in the cemetery, as opposed to treating them like criminals – to the extent that they’d even etch the symbols of their trade onto their matzevah (gravestone), stamped with the wish that their souls be bound in the bonds of eternal life.

“Although at first glance it seems like a reasonable assumption, this is because the skull and cross bones survive to the present consciousness only as symbols of piracy. However, actually they were symbols of death, and in the period in question they were often carved on tombstones of fine, upstanding people.

“The skull and cross bones are known as a Memento Mori, a reminder of our own mortality if you will, the hourglass also serves as a reminder that the sands of time are running out.”

Mental Floss from the blogosphere emphasizes piracy’s financial impact on the Jewish community: “What then can we understand of Jamaica’s three-century-old Hebrew tombstones? Certainly Jews were involved in the island’s main industry of piracy. But military forces, whether government-sanctioned or mercenary, march – and sail – backed by an elaborate infrastructure. Aside from those who attacked Spanish shipping were Jews involved in provisioning, sail making, weapons sales, etc. No doubt others fenced the stolen goods the pirates acquired. And still others provided the taverns and prostitutes on which pirates squandered their ill-gotten gains.”

Placing the skull and crossbones found at the Hunt’s Bay Cemetery in a wider cultural context, the symbol is a fairly common motif intended to inspire piety that one can see in other historic Sephardi cemeteries, such as in Hamburg Altona in Germany, The Hague and Ouderkerk in the Netherlands, and the burial grounds of Queen Mary’s College, Mile End in the East End of London, England.

Piracy was prohibited in Jamaica in 1687 and in the Bahamas in 1717. Sir Henry Morgan’s long struggle to clear his reputation suggests that the disreputable occupation was not one a dead pirate’s family – Jewish or gentile – would want to memorialize on the tombstone of a deceased relative.

The cultural meaning of piracy has shifted. Originally feared as bloodthirsty marauders, today Caribbean pirates have become benign figures akin to Robin Hood. Pharmaceutical companies have phased out the skull and crossbones, which once meant poison, lest children mistake the symbol as something cute and friendly. Like Barney the Dinosaur.

From Halloween to Purim, the piracy party rocks on

What are Jews to make of figures like Koriel, Henriques, Abrabanel and Lafitte? Were they heroes or villains?

Certainly Lafitte was a good guy, according to Aileen Weintraub’s book Jean Lafitte: Pirate-Hero of the War of 1812. A Yankee hero who defeated perfidious Albion.

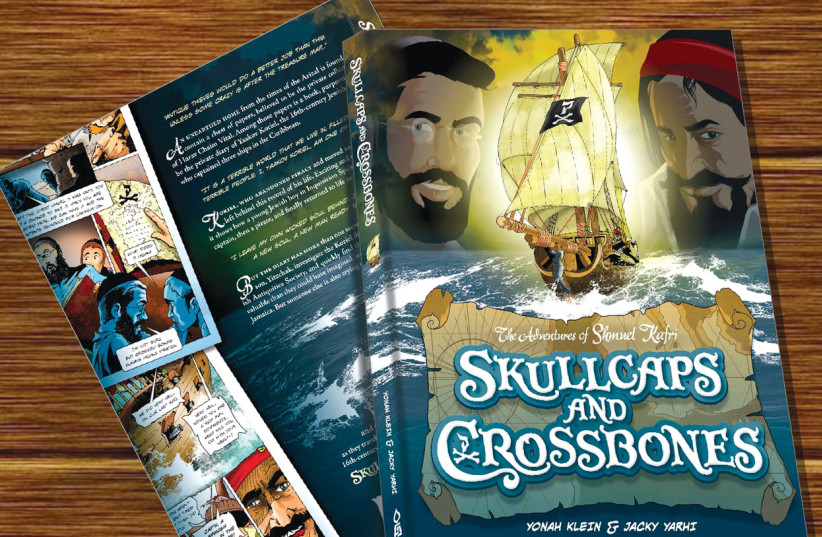

The graphic novel Skullcaps and Crossbones: The Adventures of Shmuel Kafri by Yonah Klein and Jacky Yarhi strikingly portrays Koriel as a ba’al teshuva (penitent) freed of any moral stain. In the tradition of rogue-turned-tzadik Raish Lakish – a Roman gladiator who became a sage of the Mishna – the book reveals:

“An unearthed home from the times of the Arizal [sic] is found to contain a chest of papers, believed to be the private collection of Harav Chaim Vital. Among those papers is a book, purporting to be the private diary of Yaakov Koriel, the 16th-century Jewish pirate who captained three ships in the Caribbean.

“Koriel, who abandoned piracy and moved to Eretz Yisrael, left behind this record of his life. Exciting and moving in turn, it shows how a young Jewish boy in Inquisition Spain became a naval captain, then a pirate, and finally returned to life as a religious Jew.

“But the diary has more than one secret. Shmuel Kafri and his son, Yitzchak, investigate the Koriel diary on behalf of the Jewish Antiquities Society, and quickly find that the diary is even more valuable than they could have imagined, well worth a trip to Israel and Jamaica. But someone else is also trying to get his hands on the diary.”

In a similar vein is Gary Barwin’s Yiddish For Pirates. From a present-day Florida nursing home, Aaron – a wisecracking polyglot parrot – guides bar mitzvah boy Moishe through a world of pirate ships, Yiddish jokes, treasure maps, the Spanish Inquisition and Kabbalistic hijinks.

Far be it from this writer to criticize others endeavoring to bring children to Torah and make them proud Jews. By all means, invoke the remarkable stories of Jewish pirates.

But if Koriel is a hero, what about gangster Bugsy Siegel, who in 1948 gave Golda Meyerson a suitcase stuffed with cash to buy guns for the War of Independence they both knew was coming? And what of Siegel’s partner in crime Meyer Lansky, whose application in 1970 to make aliyah was rejected? It’s a slippery crime-doesn’t-pay slope until one descends to the private hell of remorse for Bernie Madoff, who made the unpardonable sin of ripping off fellow Jews and tzedaka funds in his Ponzi scheme.

Closer to home, Benjamin Netanyahu is returning to the Prime Minister’s Residence on Balfour Street, even as his corruption trial continues. The case of former Jerusalem mayor Uri Lupolianski suggests the moral dilemmas facing a Jewish pirate; Hizzoner donated his ill-gotten gains to his favorite charity. No doubt, many Jewish pirates saw themselves as avenging the crimes of the Inquisition. Like all of us, they were complex figures with varied motives. Revenge was one. Greed was another.

The Jewish pirates of the Caribbean is a subject that deserves ongoing research. In conclusion, were there Jewish pirates in the Caribbean? Aye.

Were other Jews involved in piracy’s ancillary businesses? Oy!

But were the Jews lying beneath the three century-old tombstones in Kingston, Jamaica, decorated with skull and crossbones pirates? Nay.

Alas, dead men tell no tales. ■

Sun, sand and synagogue

The ark in the historic Sha’arei Shalom Synagogue in Kingston, Jamaica, contains 13 Torah scrolls, preserving those brought from the island’s five defunct synagogues. The synagogue, with its sand-covered floor, is one of five similar houses of prayer in the Caribbean today, including St. Thomas, Barbados and Curaçao. The tradition may date back to the 1600s in northern Brazil, where conversos needed to keep their religious practice secret from the ecclesiastical authorities. The sand or clay floors muffled their prayers.

In 2010, the restored Zedek ve-Shalom Synagogue from Parimaribo, Suriname, went on permanent display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The neoclassical wooden building erected in 1736 is modeled on the Esnoga – Amsterdam’s landmark Spanish and Portuguese synagogue – which was the mother synagogue for the Sephardi Caribbean congregations.