‘A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

William Shakespeare’s words in Romeo and Juliet invoke a powerful image. Do the words we choose matter? Do they have a visceral effect on the world around us? Does the name of a rose change its scent?

I spent much of my week on another Shakespearean archetype, that of Shylock. In The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare sculpts a character who is the ultimate in greed, avarice and dishonesty. Shakespeare in fact had never met a Jew, as they had been expelled from England centuries before his birth. Still, Shakespeare not only made his Shylock Jewish but made it the center of his personality and referenced it repeatedly. This antisemitic stereotype, much continued in the centuries that followed, sought to counter the Jewish moral message, and accuse Jews of duplicity and gluttony.

The issue came up this week in my home state of Kentucky. During a committee meeting in the Kentucky State General Assembly, in a light-hearted moment about a one-dollar state contract, a representative asked if the price could be Jewed-down. The senator leading the committee repeated the comment before recognizing that perhaps it was a poor choice of words.

As chairman of the Kentucky Jewish Council, I reached out to both men. They both expressed that they meant no malice by the comment and were unfamiliar with its origin.

I took the opportunity to educate them about the enduring antisemitic tropes of Jews and business, going back to Shakespeare’s Shylock and beyond, continuing even today. I spoke about the pogroms and expulsions that Jews faced throughout history, and how often they were tied to myths of unscrupulous Jewish business practices.

I spoke about the caricature of the immigrant Jew in the early 20th century, and the role it played in America’s decision to close its doors and turn its back on European Jewry during the Holocaust. I also shared examples of how often these tropes were used by Stalin to target Jews in Russia and by Hitler to castigate the Jews in the build-up to the Holocaust.

I shared that this issue was personal to me, as I am the second rabbi in history to be born in Kentucky and serve here, as it is to the entire Jewish community in the Commonwealth. I spoke about General Order 11, when during the Civil War, Ulysses S Grant, expelled the Jews of Kentucky on penalty of death, partially for their supposed business practices.

I spoke about Quintez Brown, the prominent Black Lives Matter activist who, less than a couple of weeks ago, after posting antisemitic tropes of Jews and business, attempted to assassinate Craig Greenberg, a Jewish candidate for mayor of Louisville, Kentucky. I explained that even without malice, tropes like Jew it down create tremendous harm and propagate dangerous ideas.

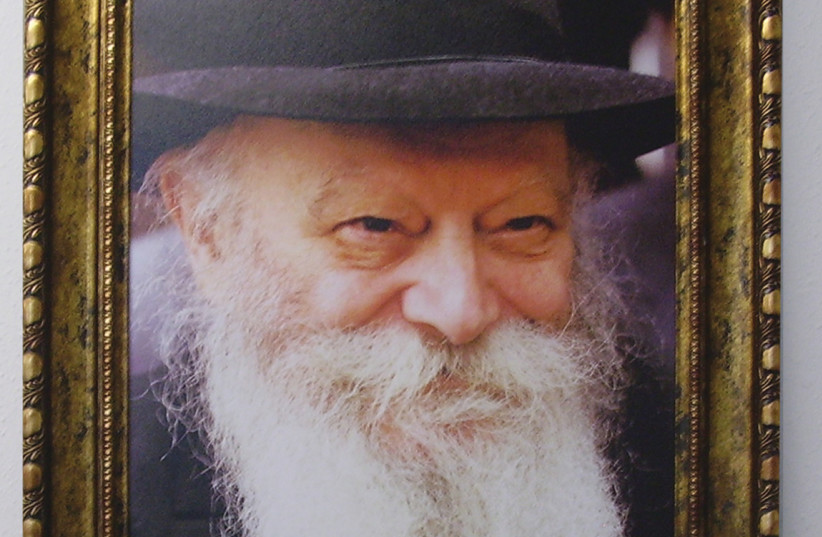

The Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, my personal mentor and the foremost Jewish leader of the modern era, often spoke of the intentionality of words. When speaking to a leading medical professional from Israel, he championed the term beit refuah over beit cholim, suggesting a hospital should be called a house of healing rather than a house of sickness.

When the Rebbe met with a delegation of injured IDF veterans, he rejected the term disabled, choosing instead mitzuyanim, or exceptional soldiers. His advocacy for the same when discussing cognitive disabilities promoted the terms special needs and special education long before it became the international norm.

The Rebbe encouraged the use of positive words and spoke of their practical effect. Indeed, one of the first grammar lessons I give my own children is instead of saying bad, say not good. Grammar is not only using the correct vocabulary but proper aspiration and thoughtfulness as well.

Even when discussing something seemingly negative, we can choose words that project positivity. All the more so in our daily conversations, it is incumbent upon every one of us to carefully monitor our word choice and recognize the tremendous power of our words.

While it may be true that the name Rose does not affect the scent of the flower, the words we choose radically impact the person speaking and the society around us. When words of hate are not countered, acts of violence are bound to follow. Even without the intended impact, words of hate affect our society. Words of love and positivity do the same.

The legacy of Shakespeare’s negative words still wreaks havoc in our society. Lehavdil, in stark contrast, the lesson of the Rebbe’s choice of positive words continues to impact our world for the better. It would benefit us all to consider the power and impact of the words we choose.

The writer, a rabbi, is chairman of the Kentucky Jewish Council.