The trauma refuses to age.

The Yom Kippur War, which raged 48 years ago this month, remains for thousands of Israelis a combination of Pearl Harbor and Watergate; a tale of military shock and political decadence that cost thousands of lives and dethroned an arrogant elite.

Now, though it’s been nearly half a century, the events of October 1973 are stirring renewed debate.

“The Yom Kippur War was an unparalleled victory,” wrote Haaretz columnist Israel Harel. “Where else in the annals of warfare,” he asked, “did numerically inferior forces manage to turn a war’s tide and within 16 days rout two big armies? Where did the war end? In the outskirts of Tel Aviv or in the outskirts of Cairo and Damascus?” asked the former settler leader, who was among the paratroopers who crossed the Suez Canal.

Hebrew University’s Shlomo Avineri concurred. “A distorted image of the war has taken root in Israeli discourse,” wrote the dean of Israel’s political scientists. Yes, the war started off badly, but wars should be judged not by how they begin but by how they end. “The IDF’s ability to overcome the shock of surprise and encircle a large part of the Egyptian army that crossed the canal – ultimately led to the burial of the Arab dream of annihilating Israel,” he wrote.

True, responded military historian Azar Gat of Tel Aviv University, the IDF won, but only because Egypt made its war’s lone mistake, when it thrust armored brigades deeper into the Sinai, where they were crushed. Even that, however, did not offset the erosion of the IDF’s power, and Israel’s surrender to the foreign pressure that prevented the Egyptian Third Army’s annihilation, opined Gat.

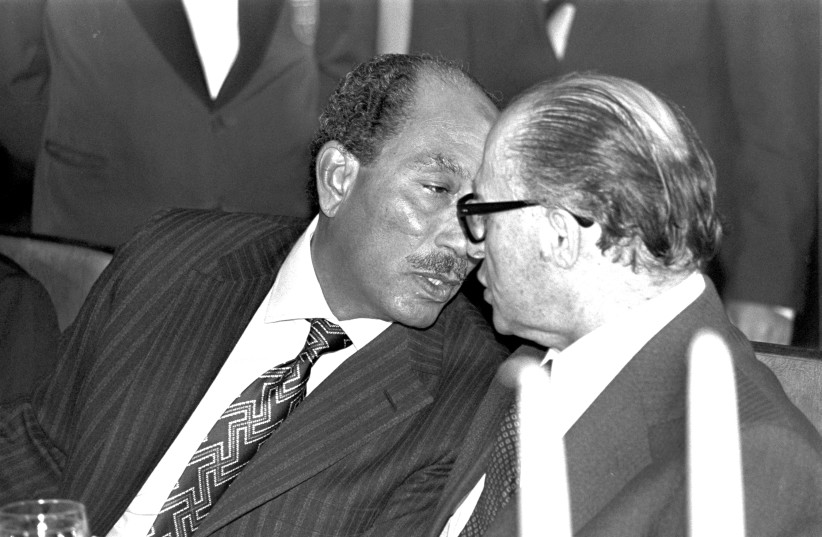

The war’s blow to Israel’s morale was compounded by an economic “lost decade,” and a new dependency on the US. Moreover, Anwar Sadat realized war’s futility already in 1970, so his strategic choice to make peace with Israel was not the fruit of Israel’s performance in the war, wrote Gat.

Historian and former foreign minister Shlomo Ben-Ami went further. Sadat was the war’s victor, he argued, because he achieved the goals he set when he went to that war, namely, peace with Israel and defection from Moscow’s orbit to Washington’s.

The common denominator between these insights is that they ask who won the war, which leads to some combination of Egypt, Israel and the US. However, the war also had three losers, and their tales are no less telling, maybe more.

ONE LOSER was the Soviet Union.

Yes, Soviet anti-aircraft and anti-tank missiles proved effective, but Soviet jets and tanks were again defeated, as they were in 1967. Worse, the largest foreign buyer of Soviet-made arms, Egypt, would now shift to American weaponry.

Diplomatically, the Soviet defeat was even harsher, because the war produced an American-brokered Egyptian-Israeli peace. Moscow thus relegated itself to Middle Eastern history’s margins, where the USSR remained until its death.

A second loser was OPEC.

The oil exporters’ cartel did not cause the war, but its members, like vultures hovering above corpses, used it to impose a global embargo that by winter ’74 quadrupled oil prices. For the West, this war-profiteering was an economic Pearl Harbor, but the West fought back, and eventually won.

The West made smaller cars, economized office-building energy and developed solar and wind power, all of which shrank oil’s demand. At the same time, the West accelerated prospecting, ultimately finding massive oil deposits in Norway and Britain, thus expanding supply.

The result was a collapse in oil prices that rendered the 1973 embargo a Midas Curse. OPEC’s leaders condemned their countries to easy money’s industrial lethargy, economic degeneration and, in the cases of Libya, Iraq and Venezuela, to political mayhem and social collapse.

Even so, all these losers pale compared with the Yom Kippur War’s biggest loser – Syria.

THE EXTENT to which Syria and Egypt were in sync as they planned their joint attack is unclear.

Riddles abound: Did Sadat tell Hafez Assad he would use the war to seek peace? If he did, how did Assad respond? If he didn’t, why did Assad’s tanks not proceed from the Golan to the Galilee?

Whatever they discussed before the war, when it ended, its Arab allies parted ways. Sadat chose peace, Assad clung to war.

Assad saw Israel, and also Lebanon, Jordan, much of Iraq and also a sliver of Turkey as parts of a Greater Syria. That’s why he invaded Lebanon in June 1976, and that’s why, as defense minister and Syria’s de-facto ruler in 1970, he invaded Jordan.

The same warring attitude governed his post-1973 fiscal policy, which sought “strategic parity” with Israel, an economic absurdity and a recipe for disaster.

Sadat wanted prosperity. That’s why he defected to the West. The Soviets offered military aid, but unlike Uncle Sam they could give no economic aid. Sadat’s economic plans were sadly neglected after his assassination, but they were wise, and could have been his career’s crowning achievement.

Assad didn’t care about prosperity. His Syria thus became a poor country with a huge army.

The warring attitude filtered to ethnic policy, underscored by the oppression of the Kurdish minority, whose members were not even given citizenship, and the repression of the Sunni majority, which included the 1982 massacre in Hama.

Syria’s dive into the Yom Kippur War was the prelude to all this madness, which in turn sowed the civil war which left Syria staring at leveled cities, brimming cemeteries and millions of orphans, widows and refugees.

Fed by the economic suffocation, sectarian alienation, diplomatic rejectionism, military adventurism and culture of hatred that its previous leadership chose, today’s Syria is the direct product of the path its leaders carved in 1973. That is why the Yom Kippur War’s biggest loser is Syria, God save her.

Amotz Asa-El’s bestselling Mitzad Ha’ivelet Ha’yehudi (The Jewish March of Folly, Yediot Sefarim, 2019), is a revisionist history of the Jewish people’s leadership from antiquity to modernity.