An Olympic medalist and Holocaust survivor, Karoly Karpati epitomized Jewish strength

For Karoly Karpati, there was no such thing as turning the other cheek, even to a Nazi guard.

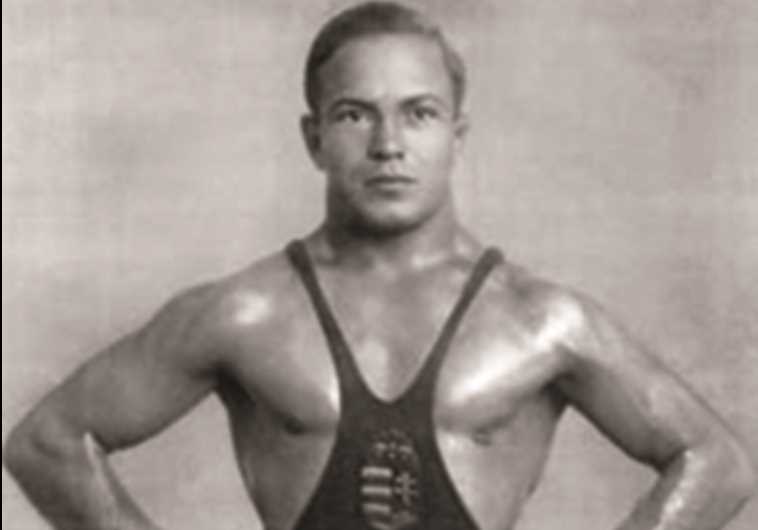

Olympic medalist and Holocaust survivor Karoly Karpati(photo credit: INTERNATIONAL JEWISH SPORTS HALL OF FAME)

Olympic medalist and Holocaust survivor Karoly Karpati(photo credit: INTERNATIONAL JEWISH SPORTS HALL OF FAME)