A 15-century comedic manuscript, making fun of the social powers of the time, has shed new light on medieval society and the source of British humor, a new study published on May 31, 2023, has found.

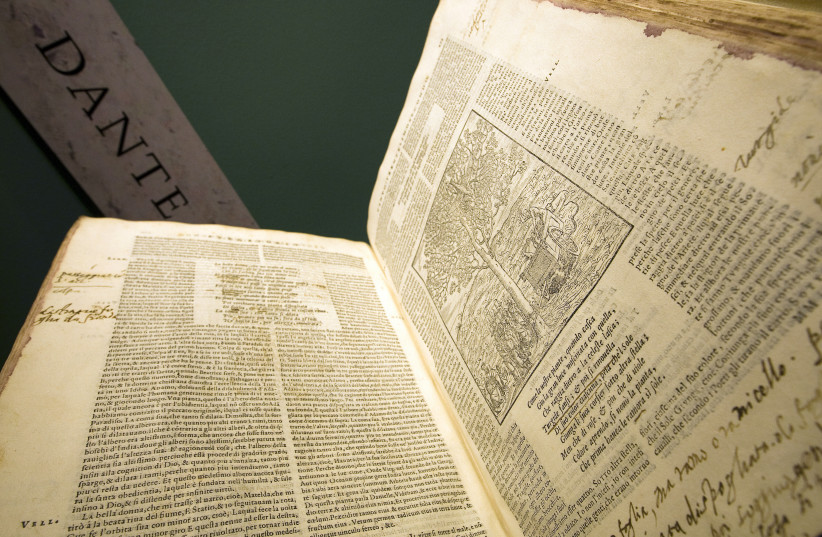

The peer-reviewed analysis, published in The Review of English Studies, inspected the first of nine booklets in the “Heege Manuscript.”

The booklet contains three texts: The Hunting of the Hare, a mock sermon in prose, and The Battle of Brackonwet.

The significance of medieval comedy

The texts had been stumbled across by Dr. James Wade, from the English Faculty at the University of Cambridge and Girton College. While the manuscript had undergone previous analysis, the other researchers had primarily focused on the physical construction of the booklet and hadn’t appreciated it for its literary value.

Wade realized the uniqueness of the text when he read the note, written by a scribe, “By me, Richard Heege, because I was at that feast and did not have a drink."

"It was an intriguing display of humor and it's rare for medieval scribes to share that much of their character," Wade explained in a press release.

While manuscripts from the period are already considered to be rare, the daring nature of the texts makes the find something of particular interest, Wade clarified.

"Most medieval poetry, song and storytelling has been lost," Wade said. "Manuscripts often preserve relics of high art. This is something else. It's mad and offensive, but just as valuable. Stand-up comedy has always involved taking risks and these texts are risky! They poke fun at everyone, high and low."

"These texts are far more comedic and they serve up everything from the satirical, ironic, and nonsensical to the topical, interactive and meta-comedic. It's a comedy feast," Wade added.

Culture of comedy in Britain

The texts were likely made for a live performance, Wade explained. The narrative voice, a minstrel, breaks down the fourth wall, asking his audience for a drink and to pay attention.

A minstrel was a type of medieval entertainer, sometimes a musician, who sang or recited lyric or heroic poetry for the purpose of entertainment. Minstrels often engaged in other work during the day and performed in their free time.

The minstrel’s comedic legacy continues to permeate in British society, Wade stated. “You can find echoes of this minstrel's humor in shows like Mock the Week, situational comedies and slapstick. The self-irony and making audiences the butt of the joke are still very characteristic of British stand-up comedy."

"Here we have a self-made entertainer with very little education creating really original, ironic material. To get an insight into someone like that from this period is incredibly rare and exciting."

"People back then partied a lot more than we do today, so minstrels had plenty of opportunities to perform. They were really important figures in people's lives right across the social hierarchy. These texts give us a snapshot of medieval life being lived well."

The jokes are believed to have been primarily designed for a local audience, having made references that would have been appreciated by locals at the time.

"These texts remind us that festive entertainment was flourishing at a time of growing social mobility."

Analysis of the manuscript

The Hunting of the Hare is a poem featuring medieval peasants and their misadventures. Some have suggested that the poem bares similarities to the British comedic act Monty Python’s episode ‘Killer Rabbit of Caerbannog.’

"Jack Wade was never so sad / As when the hare trod on his head / In case she would have ripped out his throat."

"Killer rabbit jokes have a long tradition in medieval literature. Chaucer did this a century earlier in the Canterbury Tales."

In the Wife of Bath's Prologue, the audience is addressed as ‘cursed creatures’ and drinking songs are embedded throughout.

The manuscript recites "Drink you to me and I to you and hold your cup up high" and "God loves neither horse nor mare, but merry men that in the cup can stare."

Wade explained that particular line of text was "a minstrel telling his audience, perhaps people of very different social standing, to get drunk and be merry with each other."

While the minstrel may have joked about drinking, he used his audience as an opportunity to make political commentary and ridicule ruling powers. In one text, he describes kings eating so much that 24 oxen burst out of their stomachs. This is also the first recording time that the phrase ‘red herrings’ is used, as it was said that the oxen chopped each other up until they were reduced to “red herrings.”

A red herring is “a clue or piece of information that is, or is intended to be, misleading or distracting,” according to the Oxford Language Dictionary.

"The images are bizarre but the minstrel must have known people would get this red herring reference. Kings are reduced to mere distractions. What are kings good for? Gluttony. And what is the result of gluttony? Absurd pageantry creating distractions, 'red herrings,'" Wade explained.