“The degree of justice in a country is measured not by the rights accorded to the native-born, the rich, and the well connected but by the justice meted out to the unprotected stranger.”

“The degree of justice in a country is measured not by the rights accorded to the native-born, the rich, and the well connected but by the justice meted out to the unprotected stranger.”

Samson Raphael Hirsch

Although these words were said nearly a century and a half ago by German rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch to a German Jewish audience, its message resonates today in the life story of Maryam Younnes, a southern Lebanese Christian refugee turned Israeli citizen and patriot.

Younnes was born in 1995 in Debel, Lebanon, a Maronite village about an hour’s drive from northern Israel. In the very green grassy village, her family worked as tobacco farmers, planting young tobacco shoots in the firm soil. She grew up with cows, horses, and sheep among her close circle of friends amid the low and slow bleats and neighs of the barnyard.

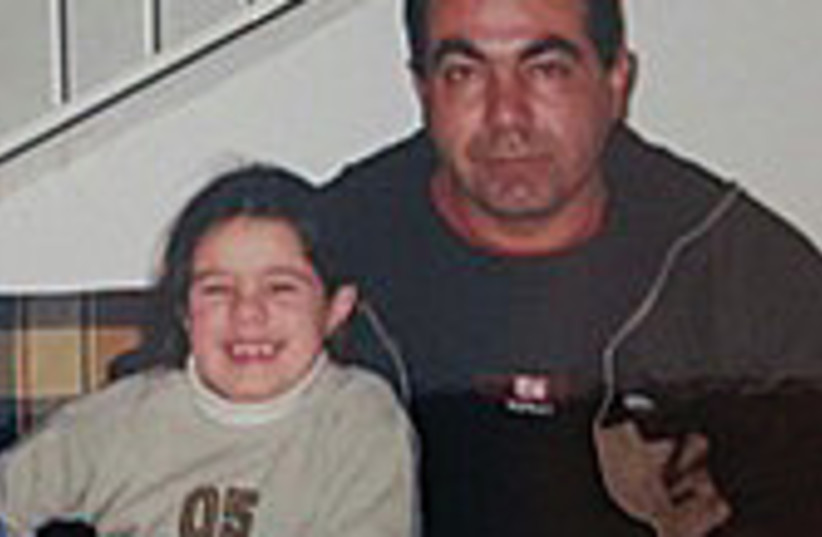

However, life wasn’t as idyllic as it might seem. She was born in a war zone during the southern Lebanese conflict. From 1985 until 2000, the sky above the Younnes farm was punctuated with artillery sounds and muffled explosions. The military conflict didn’t just shatter her peace on the farm; it fractured her family as well. Her father, Elias Younnes, assumed a commanding position in the freedom-fighting South Lebanon Army (SLA), leaving young Younnes without many childhood memories of her father.

Speaking to me at a cafe near Bar-Ilan University campus, she now understands the religious strife, politics and social issues that caused the deafening falling night sky she recalls from her early childhood.

The story of the Christian SLA, Lebanon, Hezbollah and Israel

In 1982, in response to attacks by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) on northern Israeli communities, Israel invaded Lebanon. They partnered with the Christian SLA, which was fighting its own war against the PLO, which it regarded as an intruding destabilizing force in the region. With the help of the local SLA, which had substantial knowledge of the terrain, Israel was able to seize large parts of Lebanon, including the capital, Beirut, which itself was war torn due to the ongoing Lebanese civil war between the Christian and Muslim populations. Israel’s aim was to rid the Israel-Lebanon border of the PLO, and then withdraw from Lebanon. The tide of the conflict turned against Israel when, with Iranian support, local Shi’ite groups began to unify to resist the Israeli occupation. Using tactics of guerrilla warfare, this nascent militant group, later known as Hezbollah, repeatedly attacked Israeli forces in southern Lebanon.

Mounting casualties on both sides over the course of several years led Israel to withdraw from most of the occupied territory between 1983 and 1985, leaving only select border areas within an Israeli-imposed “security zone.” Israel maintained control over these areas in an attempt to create a buffer between the Hezbollah terrorist militants and Israeli citizens living in northern Israeli towns close to the border.

It was common knowledge in Israel that the security zone was not permanent, but with no clear end game in Lebanon, Israel’s losses only grew as Hezbollah increased rocket attacks on the Galilee. The purpose of the security zone — to protect Israel’s northern communities – began to seem contradictory.

Following the 1997 Israeli helicopter crash, which resulted in 73 deaths, and the emergence of the Four Mothers movement, which advocated for the return of their “fighting children,” the Israeli public began to question whether the Israeli position in southern Lebanon was worth maintaining and moved the public in favor of a complete withdrawal. At first, the Israeli government hoped that a complete withdrawal from southern Lebanon could be used as a leveraging tool for peace with Syria and Lebanon. However, talks with Syria failed, leading Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak to follow through on his election campaign promise. On May 24, 2000, he withdrew the IDF from the security zone.

Israel’s withdrawal resulted in the immediate collapse of the SLA and the complete takeover of Hezbollah. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah threatened on national news that anyone who aided Israel would be killed in their sleep, along with their children. The SLA felt betrayed by Israel for withdrawing without securing protection for them after having fought beside them for 20 years, and by Lebanon for forcing them to flee their own country.

An estimated 7,000 Lebanese refugees swarmed the Galilee in response to Hezbollah’s threats of executions and torture, including the Younnes family.

That May, Younnes was five years old, her younger sister was three, and the youngest was only 20 days old. “I remember the night my dad called my mom,” she recounted. “He said, ‘Take the girls and come to the border. We’re going to Israel.”

He instructed her mother to pack the belongings they would need for three days “and when things calm down, we will go back to Lebanon. So don’t worry,” he reassured her. All she remembered was that it was a cold night and that her mother cried for hours. That night, they stayed at a hotel in Tiberias, where Younnes tasted Israeli chocolate for the first time. Later, they were moved to a hostel, where they stayed for eight months.

The Israeli government provided monetary grants to the refugee families, and many charity organizations donated clothing and other essentials. Elias Younnes started a business, and the family was able to get by. However, many weren’t able to support their families and relied heavily on government assistance.

Soon after, Younnes began school in Nahariya – an educational facility that was created to help integrate the refugee children into Israeli society. “Over time, we realized that Israel would not be getting rid of Hezbollah,” she explained, “and by the time of the 2006 war, they [Hezbollah] were still there and even stronger than before.”

“Over time, we realized that Israel would not be getting rid of Hezbollah, and by the time of the 2006 war, they [Hezbollah] were still there and even stronger than before.”

Maryam Younnes

Younnes considers herself among the lucky ones. Her entire extended family – her grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins – who had stayed behind in Lebanon told her immediate family not to return. “The situation in Lebanon is horrible now, economically and politically,” they lamented. “There is nothing to come back for.” Nowadays, no one can cross the border, not Israelis nor Lebanese. “We are forbidden from going there. We are banned. Only if I give up my Israeli citizenship can I return to Lebanon, and I wouldn’t do that,” Younnes said proudly.

She wouldn’t be welcome there any time soon, she explained, “because I speak out against Hezbollah. I think my name is on some kind of black list in Lebanon.”

Those who served in the IDF, like her younger sisters, would have to “clean their record” before being allowed back into Lebanon, even if they agreed to revoke their Israeli citizenship, as “it is much more complicated for them.”

After the eight-month stay at the hostel, the Younnes family moved to Ma’alot, a Jewish community in northern Israel, since Muslim “Arabs wouldn’t accept us because we were ‘traitors’ for having fought alongside Israel.”

Younnes grew up with Jewish friends and went to a Jewish school. The first two years at the Israeli school were tough on her, as she was often bullied for being the only Lebanese in her Jewish Israeli school. She remembers being called a “Hezbollah terrorist” and was told to “go back to Lebanon” by “kids that didn’t understand.

What got her through those first few difficult years were her teachers, who would “stop everything” when a student would pick on her and explain how Younnes and her family had helped Israel and how grateful the students should all be that she was there. Soon her classmates would ask her to bring in traditional Lebanese cuisine like pita with za’atar and labaneh to share with the class.

Now “I speak Hebrew better than Arabic,” Younnes laughed. She became a part of both worlds; her family celebrated both Hanukkah and Christmas. To her, “it’s totally normal. This is how our community grew.”

The SLA community is now spread throughout Ma’alot, Nahariya, Safed, Kiryat Shmona Tiberias, Haifa, and Carmel. They follow a Maronite priest who was sent from Lebanon to lead their church and support religious life.

“We have managed to preserve our culture, language, and love for Lebanon despite how difficult it is,” and at the same time, “I’m very happy and lucky to be in Israel. I love Israel. I feel Israeli… On Independence Day, we make al ha’aish” (barbecue).

Younnes even served as Galila Ron-Feder-Amit‘s muse for a children’s book called Crossing Tunnels in her bestselling series “The Time Tunnel” #80, where she depicts the story of the SLA community in Israel.

In 2013, Younnes’s father passed away and was buried in Lebanon by the United Nations ground forces in Lebanon. She wants to carry on his legacy and has dedicated her life to helping the SLA community. She received her BA in communication, media, and publicity in Italy and is currently pursuing her MA in political science at Bar-Ilan University. Her thesis topic centers on the SLA youth and why they are choosing to serve in the IDF. She works at Bar-Ilan’s media office and aspires to work in foreign relations.

There are many issues that Younnes is passionate about, first and foremost, equal rights among the SLA community in Israel. When the estimated 7,000 refugees came to Israel, they were separated into two groups: SLA commanders, who were taken care of by the Ministry of Defense; and regular soldiers, who were handled by the Ministry of Integration.

As a result, the SLA commanders’ families received more money and support than the soldiers’ families. Specifically, the Younnes family were given a house, tuition grants, and larger stipends. The soldiers were considered like regular olim and had to make it on their own.

They felt mistreated and under-appreciated, as “they did not come to Israel out of their own free will. They had to run away because Israel withdrew without any pact protecting them,” Younnes said.

She has been interviewed several times and has consistently fought for their rights. “Finally, we can say that this chapter is closed.” In 2020, the Israeli government approved the proposal by defense minister Benny Gantz and finance minister Avigdor Liberman to provide financial assistance for housing in a one-time amount of NIS 550,000 to about 400 former SLA soldiers who were not in command ranks and did not receive any previous assistance from the state.

Views on the Israeli Palestinian conflict

Younnes also stands strongly on another controversy: the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. She believes that most Christian Lebanese people would agree with her in that “it is the right of the Jewish people to have a country.”

She explained that at first, Hezbollah had a justified purpose in the eyes of the Muslim Lebanese people, “defenders against the invaders who want to take over Lebanon; but now they don’t have this narrative anymore,” and they are actually harming their own people.

Many Lebanese, who at first supported Hezbollah, “understand now that Hezbollah have brought nothing to Lebanon besides war and that they work for the Iranian regime” and not for the Lebanese people. “In the media, they [Hezbollah] will show you what they want to show you, but they are losing power. There is still hope in every Lebanese person here to go back to our country. It is our country! But I don’t want to go back until there is peace. I do believe that we will have peace,” she asserted.

She said that “there is nothing wrong with identifying as Palestinian. The problem starts when people believe they should kill because of that.” She has friends who study at Israeli universities and work for Israeli companies, but they post on social media that they hate Israel. “It doesn’t make sense to me! It makes me really mad,” she said.

Younnes explained that she is “the epitome of contradiction. I am Lebanese-Israeli,” and feels passionately that if “I can find peace within myself, then mutual understanding and peace can be found between the Israeli and the Palestinian people.” ■