A fifth person suffering from HIV has been confirmed to have been cured thanks to stem cell transplant treatment, as detailed in a new study.

The patient in question, a 53-year-old German man treated in Dusseldorf, was given the transplant in 2013 and stopped taking antiviral medication in 2018, as was announced in 2019, but researchers couldn't officially confirm that he'd been cured until now.

The findings of this study were published in the peer-reviewed academic journal Nature Medicine.

How did we cure HIV?

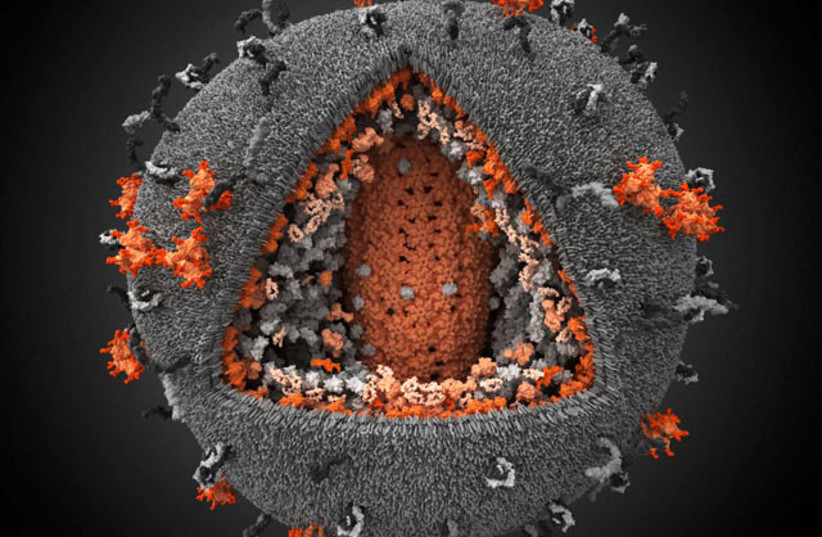

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) is one of the most infamous viruses in the world.

Since it was first discovered in 1981 after it was somehow transferred from non-human primates (primarily chimpanzees) to humans in Africa, HIV has managed to spread all over the world.

The virus is spread primarily by unprotected sex, contaminated blood transfusions, hypodermic needles or from mother to child during pregnancy.

HIV symptoms themselves are rather mild and can often be hard to notice. However, as time goes on, the disease attacks the immune system, causing several other chronic conditions and illnesses to develop.

If left untreated, HIV will eventually develop into AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), a severe immunodeficiency that sees the immune system so severely damaged that it can cause illness from diseases that otherwise wouldn't cause symptoms in a healthy immune system.

Because of how easily you can get severely ill, AIDS is an especially dangerous condition and it has killed over 40 million people worldwide by 2021, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

There are some HIV treatment methods available to manage the condition, especially stopping HIV from progressing into AIDS. However, it isn't always easy – HIV is known for being able to hide dormant in the body, invisible to both medicine and the human immune system.

In addition, there is no accepted permanent cure for the virus.

Despite this, some people have been cured of HIV.

The Dusseldorf patient, like most of the other cases, was cured thanks to a stem cell transplant.

But just because several people have been cured doesn't mean there is now certainly a cure.

How did the HIV cure work and why is it too risky to be used for everyone?

It is important to note that while stem cell transplants have shown significant promise in potential medical applications, they still come with severe risks.

Patients who receive stem cell transplants are at high risk from a number of severe complications such as sepsis, veno-occlusive disease, mucositis and a number of different types of cancer.

And not only that, but it's also possible that the condition the stem cell transplant is supposed to treat will just return anyway. For all of these reasons, people who have received stem cell transplants often have a high mortality rate, according to many estimates.

It is for this reason that it isn't used as a treatment so freely, but only in extreme cases.

HIV alone isn't enough to qualify as an extreme case. What made the Dusseldorf patient's case severe enough to have a stem cell transplant was that he also was sick with acute myeloid leukemia.

The combination of both conditions was enough to risk the transplant. This was also the case with all patients cured of HIV through stem cell transplants – each of them had some form of leukemia.

The reason the stem cell transplant was able to cure HIV in these patients though was because of a genetic mutation from the donor.

This mutation, known as CCR5 delta32, is known to have qualities allowing it to resist HIV. This is because it is the body's CCR5 receptors that HIV targets to infect the cells. A mutation in these receptors would prevent it from doing so.

The logic is that the stem cells containing CCR5 delta32 could help transform the patient's immune system to allow it to resist HIV.

And as the study notes, it worked – there was no HIV detected in the patient, even four years after stopping antiviral treatments.

But because of the risky nature of this treatment, it is by no means an easily acceptable cure. Especially since there is no indication that leukemia won't simply come back. In fact, one of the patients cured of HIV through stem cell transplants actually died when his leukemia relapsed.

Other cases of HIV being cured

In addition, it should be noted that there have been other cases of HIV being cured without the use of stem cell transplants. In fact, some seemed to just happen for no reason at all.

One such case happened in 2020 when a woman from San Francisco who had HIV since 1992 seemingly no longer had any traces of HIV in her body's cells, despite not receiving any special treatment.

Another case revealed in 2022 showed an Argentinean woman who also seemingly no longer had any traces of HIV within her system despite receiving little to no treatment.

The theory posited by AIDS specialist Dr. Javier Martinez-Picado at the AIDS 2022 conference is that some people have "exceptional elite control," allowing them to just completely fight off HIV with their own immune system somehow.

It is this phenomenon, Martinez-Picado argued, that could help lead the way to find an HIV cure.

Shira Silkoff contributed to this report.