Following the outbreak of Afghanistan’s civil war in 1992, the museum was repeatedly shelled. It suffered heavy damage in a May 12, 1993 rocket strike. The combination of Taliban mortars and looters resulted in the loss of 70% of the 100,000 prehistoric, Hellenistic, Buddhist, Hindu, Zoroastrian, Islamic and Jewish objects once in its collection. Those pilfered artifacts flooded antiquities markets in London, Paris, New York and elsewhere. Now the pro-Western regime of President Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai – formerly an anthropology professor at John Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland – wants its cultural legacy returned. Among those treasures it is seeking to repatriate is a 1,200-year-old siddur (prayer book) – the world’s oldest Hebrew manuscript after the Dead Sea Scrolls.

“It is our responsibility to get back our ancient treasures,” said Abdul Manan Shiwaysharq – the country’s Deputy Minister for Information and Publications in the Information and Culture Ministry – in the first-ever on-the-record interview between an Afghani official and an Israeli journalist.

RESPONDING TO a query, the MotB’s chief curator Jeff Kloha said the museum will share results of an investigation when completed.

“As noted on the museum’s provenance research webpage, museum staff members continue to work with external scholars and experts to research this item’s historical and religious significance, as well the item’s history in (apparently) Afghanistan and later Israel and the United States,” Kloha said. “That research is progressing and nearing completion.”

That web page includes a note about the siddur, described as an Early Jewish Prayer Book:

“This item was acquired in good faith in 2013 after receiving provenance information dating back to the 1950s in the UK. The item was legally exported from the UK. It has been displayed in the US, Israel, and published widely among international news outlets since September 2014. Subsequently, a Museum of the Bible curator discovered published images of the book from 1998, in which the book appears to have been photographed in Afghanistan. Subsequent research has not yet determined the find spot or history of the item prior to 1998. Curators continue to advance this significant research project.

“Nevertheless, this Siddur is an exceptional item of unique historical, cultural and religious significance, and presents great educational potential. In addition to ongoing provenance research, a book project is underway with contributions from specialists in handwriting, manuscript production, Jewish history in Afghanistan, and Jewish liturgical practices. This book project will make the Siddur available for research and enable additional contributions to this one-of-a-kind manuscript.”

Kloha previously told National Public Radio that problems with the museum’s early acquisitions were due to a lack of expertise and lack of policy at the time.

The allegation that the MotB’s rare Afghan Hebrew prayer book is another ancient Near Eastern treasure that was smuggled out of its country of origin – perhaps with the collusion of museum staff sympathetic to the Taliban who don’t regard Judaica as part of Shi’ite Afghanistan’s cultural legacy – is the latest in a series of scandals about looted and forged antiquities that has rocked the Museum of the Bible since its 2017 opening in the American capital.

Hoping to restore a tarnished reputation, the museum recently shipped 8,000 clay tablets back to Baghdad that may have been taken from The Iraq Museum in 2003 when looters overran it during the American invasion that toppled Saddam Hussein. The vaguely documented collection was acquired from licensed antiquities dealers in Israel, the US and the UK, and includes clay impressions of seals and incantation bowls meant to ward off demons thousands of years ago.

Hobby Lobby (whose CEO founded and funded the Museum of the Bible) is also suing Christie’s auction house over a 3,500-year-old Sumerian cuneiform tablet inscribed with part of the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh creation poem. Christie’s claims it wasn’t aware the documents it relied on were forged. US Homeland Security agents seized the 15-by-12.5-cm. tablet from the museum last September, and now are seeking to return it to Iraq. The Oklahoma City-based chain alleges that, in orchestrating the sale, the auction house violated America’s National Stolen Property Act.

At the end of January 2021, the US Department of Homeland Security returned 5,500 papyri fragments and other pharaonic artifacts from the Museum of the Bible with “insufficient” provenance to Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, concluding Cairo’s efforts since 2016 to regain its antiquities.

Equally embarrassing, the MotB has acknowledged that all of the Dead Sea Scroll fragments it acquired are forgeries.

Billionaire MoTB founder Steve Green, an evangelical Christian whose family owns the Hobby Lobby craft store chain, and chief curator Kloha have gone to great efforts to tighten the museum’s acquisition policies after the US government reached a settlement with Hobby Lobby in 2017 requiring the chain store to pay a $3m. fine for illegally importing ancient artifacts. Kabul is a signatory of a 1970 UNESCO Convention making the export of antiquities without permission from the government illegal.

LEON HILL, the in-house counsel for Transparent Business Solutions (TBSBV), a Dutch company that specializes in corporate integrity management, is keen to see a resolution to the dispute over the ownership of the ancient siddur.

Interviewed from Bali, Indonesia, the member of the California Bar Association confirmed his company is in negotiations to represent Kabul.

“We’re developing discussions. We are very pleased with the progress we have made.”

Hill is dismissive of Green’s explanation that he and Kloha are novices in the museum business and the acquisition of artifacts.

“They can’t continue to say that. They’re no longer new. They have a duty to know better. They have a duty to the history and heritage of the artifacts they purport to protect.”

He accused the MotB of “cultural imperialism.”

“We hope that we won’t need to be hired by the Afghan government, and that the Museum of the Bible will do the right thing in the right way quickly.”

Asked if TBSBV is seeking a retainer and hoping to lucratively exploit a poor country bountiful primarily in misfortune, Hill responded: “This is not our effort to cash in on this criminal act. Any attempt to commodify it is almost offensive. And that’s what the Museum of the Bible has done.”

Asked if he is concerned that if the fragile siddur were returned to Afghanistan, it might share the same fate as the two monumental 6th century CE statues of Buddha in the Bamyan Valley, registered on UNESCO’s World Heritage Site list that were dynamited in 2001 on orders from Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar, who declared them idols, Hill answered: “Custody doesn’t necessarily mean location.”

“Being in possession of stolen documents is not a responsible way to curate these artifacts,” he added.

Let the MotB celebrate them with people who appreciate them, he urged, suggesting that one solution would be for the Afghan government to loan the siddur and other medieval Judaica from the National Museum to the Shrine of the Book and Israel Museum in Jerusalem which house some of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Aleppo Codex, and other ancient Hebrew manuscripts.

Shiwaysharq, who has been the target of repeated assassination attempts, acknowledged his war-torn country’s security situation is poor, and that an international tour of his country’s repatriated treasures would be a positive step toward improving Afghanistan’s standing in the world.

Since 2007, a number of international organizations have helped the country recover more than 8,000 artifacts, he notes, the most recent being a limestone sculpture from Germany. Approximately 843 artifacts were returned by the UK in 2012, including the famous 1st-century Begram ivories.

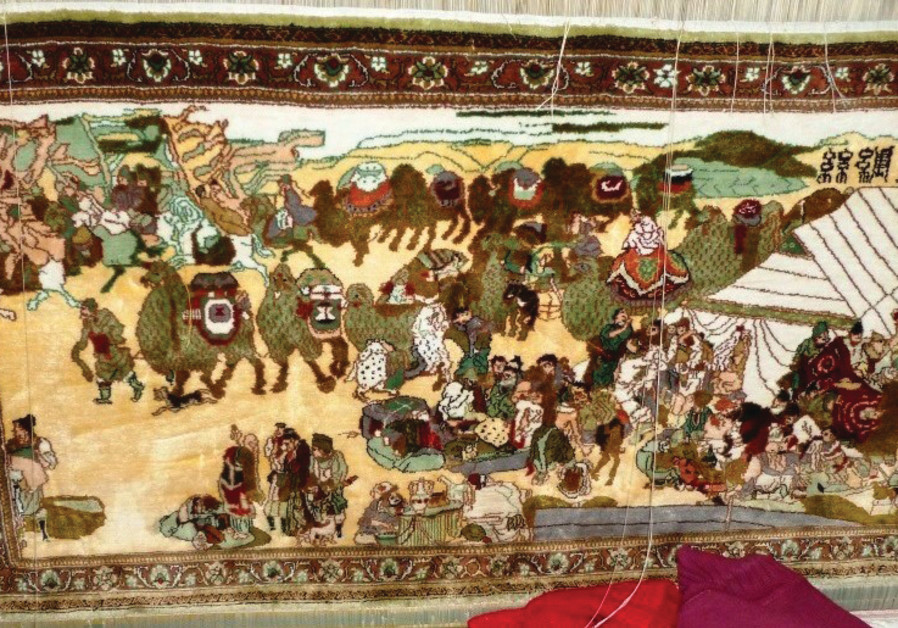

Displaying those treasures, including the Kabul siddur, could help restore Afghanistan’s long-lost status as a cultural crossroads, he added.

Joe Zias, a retired anthropologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority in Jerusalem, commented: “It’s long been time for a little transparency from the Museum [of The Bible] as to whom they were dealing with in terms of buying these objects. The world of antiquities acquisition is a little like the GOP today who know who is responsible for the mess there [is] in the US, but put their personal careers before the profession which they were obligated to protect. In the words of Seneca, ‘Academics should be lawyers for the masses.’ Many academics have failed to live up to these words.”

Asked for comment on the brouhaha, MotB director Kloha threatened, “If the article is published, the museum will consider legal action.”