In June, when the current government just entered office, a source close to Prime Minister Naftali Bennett said that unlike his predecessor Benjamin Netanyahu, the premier planned to focus on his domestic agenda and let Foreign Minister and Alternate Prime Minister Yair Lapid take the lead on international affairs.

Fast-forward to April 2022, and Bennett has dealt with the pandemic and terrorism, but he has also been trying to mediate between Russia and Ukraine to end the war, which is about as far from a domestic agenda as you can get.

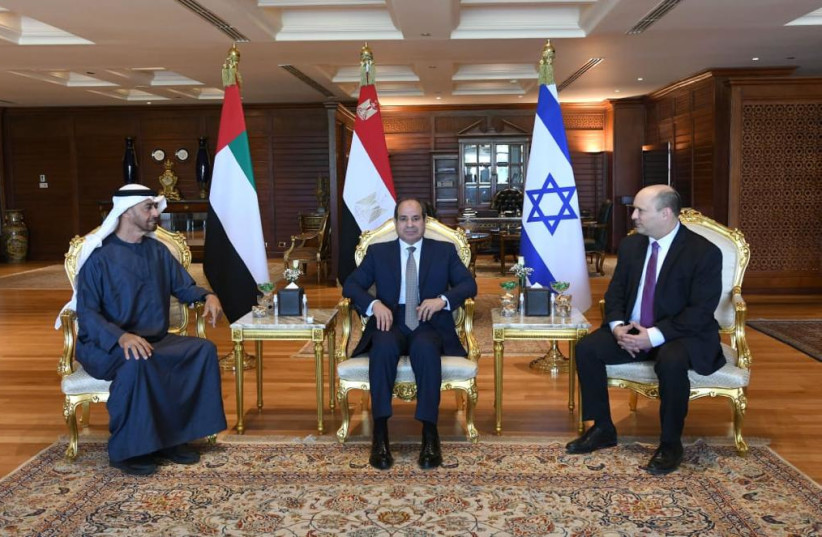

The prime minister has traveled almost every month while in office, meeting an impressive array of world leaders in Abu Dhabi, Amman, Cairo, Moscow, Sochi, Berlin, Washington, New York and Glasgow. He was supposed to be in India this week, but then he contracted corona.

Bennett was pretty successful in proving that Netanyahu is not the only one who is in “another league,” as the Likud campaign slogan went, when it comes to international relations. Arguably, many of Bennett and Lapid’s international achievements were built on a foundation erected by Netanyahu. However, they knew how to further their predecessor’s advances – like the Abraham Accords, or a close relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin – and create some of their own, like improving ties with Jordan, Turkey and the Biden administration.

International affairs are very important, of course, and any prime minister should dedicate time to them. But Bennett could have flown all the way to Wellington, New Zealand, and he still would not have escaped his domestic political woes.

For a moment, it seemed like Bennett thought it might. But being text-message buddies with British Prime Minister Boris Johnson doesn’t resolve the tensions between the conservative, religious lawmakers in his Yamina Party and the secular progressives of Meretz, among others.

Bennett constantly talked about his diverse coalition while abroad as a sort of antidote to ugly political polarization, but that polarization never really went away, and the reality became more apparent than ever when coalition chairwoman Idit Silman jumped ship to the opposition on Wednesday morning.

Not only did being active internationally not make up for a very tenuous political situation at home, but it may also have exacerbated it.

When it comes to the US, specifically, Bennett took a more conciliatory tone than Netanyahu, who was more willing to challenge Washington on Iran, and, to some extent, settlements.

Bennett chose to mostly express his disagreements with the US on Iran behind closed doors, occasionally commenting publicly when he felt the Biden administration wasn’t getting the message about the dangers of a weak, short-term nuclear agreement with the Islamic Republic.

When it came to settlements, Bennett promised he would continue moderate growth, and then was faced with a US secretary of state who constantly puts settlers at the top of its list of obstacles to peace, and a US ambassador who says settlement growth “infuriates” him.

There is no Iran-deal constituency in Israel, but settlers are an important part of the right-wing electorate and the base that brought Bennett, a former Yesha Council CEO, to his political peak – and Bennett’s effort to be on good terms with the Biden administration alienated them.

When Bennett de facto freezes building in settlements, that constituency gets mad. Last week, Bennett stood silently as US Secretary of State Antony Blinken blamed settlers for tensions in the region, when ISIS-affiliated terrorists had murdered Israelis days before.

At the same meeting, the prime minister used the term “West Bank” instead of “Judea and Samaria.” Settler leaders made sure the whole country knew they were angry with Bennett – mostly because of the settlement freeze, but the other elements didn’t help – and put pressure on his party.

Bennett might have hoped to be an international statesman above the political fray, but as Henry Kissinger famously once said: “Israel has no foreign policy, only a domestic policy.” The two matters are deeply intertwined, and Israeli leaders forget that at their peril. The rug on which they stand while shaking hands with world leaders may be pulled out from under them.