A bag of fortune cookies at the Center for Contemporary Art (CCA) Tel Aviv is not an assortment of baked goods, says art collector Philip Cohen. The edibles are a tribute to the 1990 work Untitled (Fortune Cookie Corner) by late artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres.

“Gonzales was my client,” Cohen, a periodontologist, shares, “I had many clients [like him] who suffered from AIDS. He was important to me as a collector for 15 years.”

Cohen would purchase the 1993 Gonzalez-Torres work Untitled (9 Days of Bloodwork – Steady Decline and False Hope), a work he can describe even now, 25 years later.

“Small white paintings,” he shares, “in the middle of each, a soft line with a pencil drawing of blood works. Like a slide under a microscope. This work is in my skin.”

He sold it in 2005 to finance a move to a larger house.

“I only sell when I need money,” he explains, “not to earn it.”

Cohen, like other Israeli collectors, including Oudi Recanati and Rani Rahav, combine a love of art with an eye and sense of history.

Philip Cohen

BORN IN MEKNES, Morocco, Cohen (whose Hebrew name is Pinchas), moved to Paris when he was a 12-year-old child. A successful dentist, he had been collecting art, Jewish historical postcards and furniture designed by Charlotte Perriand and Pierre Jeanneret for three decades.

Just as Jeanneret had a famous cousin, Le Corbusier (Charles-Édouard Jeanneret), so does he. The artist Pinchas Cohen Gan is his cousin. Cohen had been living here for seven years. He even helped local collectors secure Corbusier-designed furniture for their homes.

Cohen is a self-described Mécène, a French term meaning a person who supports artists. It is an old word, the person it is coined after, Gaius Maecenas, was a friend of the Roman emperor Augustus and supported Virgil.

When I ask an Israeli artist (name withheld by request) about patronage she bristles. “I do not have patrons,” she argues, “I have collectors.”

A brilliant 2006 painting by Zoya Cherkassky titled Rich People are Friends came to my mind while working on this article. It depicts a collector embracing an artist. As the patron’s back is turned to us, we observe his black suit, the luxury car, and the expression on the artist’s face as he stands in his paint-smeared pants.

“Some collectors are interested in the social impact of owning contemporary art as a trophy,” Cohen says.

“so few people know I collected outstanding works from Jewish-Moroccan Culture.”

Art collector Philip Cohen

These include preparation drawings made by Alfred Dehodencq ahead of his 1861 painting Execution of a Jewess in Tangiers. Based on the 1834 execution of Lalla Suleika for her refusal to convert from the Jewish religion to the Islamic faith, the drawings were based on Jewish women due to the refusal of Muslim ones to sit in front of a male artist. The courage shown by Suleika is the reason that North African Jews revere her memory to this day.

“The artist Joseph Dadoune was in my dental clinic,” Cohen shares, “and described how it was like to work with [late actress] Ronit Elkabetz on the production of his [2006] video art Zion.”

Dadoune described how Elkabetz told him she feels like Lalla Suleika, the beautiful woman weighed with chains before being killed.

“I asked Dadoune: ‘Would you like to see how Suleika looked like?’ He did not believe me such a thing was possible,” Cohen shared.

“When he saw the drawings he was elevated, he called Elkabetz to share the news.”

Cohen gifted the drawings to the Israel Museum, Jerusalem and is currently involved with the creation of a new Jewish museum meant to be open in Fez next year.

“If I would not have art in my life,” Cohen said, “I would get sick because I am too much a scientist. Art is my breath of fresh air.”

Oudi Recanati

OUDI RECANATI is keeping a promise to his late mother, Dina, who passed away a year ago.

Following the death of his brother Michael in 2015, he helped his mother relocate from New York to Israel with her artworks and personal archive. In it, a black and white photo from 1972 depicts Menashe Kadishman standing in front of Jerusalem Crown. The work consists of five bronze pillars the late Recanati erected outside the President’s residence.

“Siona Shimshi was her good friend,” Recanati says. Other house guests included Yohanan Simon, Emmanuel Mané-Katz, and Pinchas Litvinovsky.

The latter painter made headlines when news broke out that his grandson, Alon Din, is destroying the works he inherited. He was rejected by every museum he approached offering to gift them, Merav Moran from Haaretz reported; the reason the museums gave was that there were too many items.

Recanati procured the help of curator Ruthi Ofek for the collection after the Tefen Open Museum shut down a year ago.

Ofek, who curated it for three decades, was in charge of finding new homes for the large open-air sculptures it once displayed. The Wertheimer family sold the Industrial Park where the museum was located.

Both families, Wertheimer and Recanati, are members of this country’s moneyed elite. When its members decline to pick up the tab, museums close.

During the 1960’s, Dina Recanati was also a Mécène. Helping Discount Bank build an art collection which later proved lucrative, her son claims.

“My mother, who was an artist and a Zionist, wanted to help Israeli artists,” he said. “The idea back then was that an Israeli bank should have a collection of Israeli art.”

Dina Recanati made art for decades. Her large, colorful work Dvarim (1996) stands outside the Convention Center in the capital. Those walking to Beit Ariela Library in Tel Aviv pass her 1983 work Manuscripts. Her son gestured to large abstract paintings made on drop cloth, small metal engravings and mixed-media books as we tour the collection.

“I had her Shiva here because I wanted her to be present,” he shares, “I am not sure she would have enjoyed this decision.”

“When she was alive I gave her my word I would manage her art collection for her,” he concludes. “I am honored she wanted me to continue with this.”

Rani Rahav

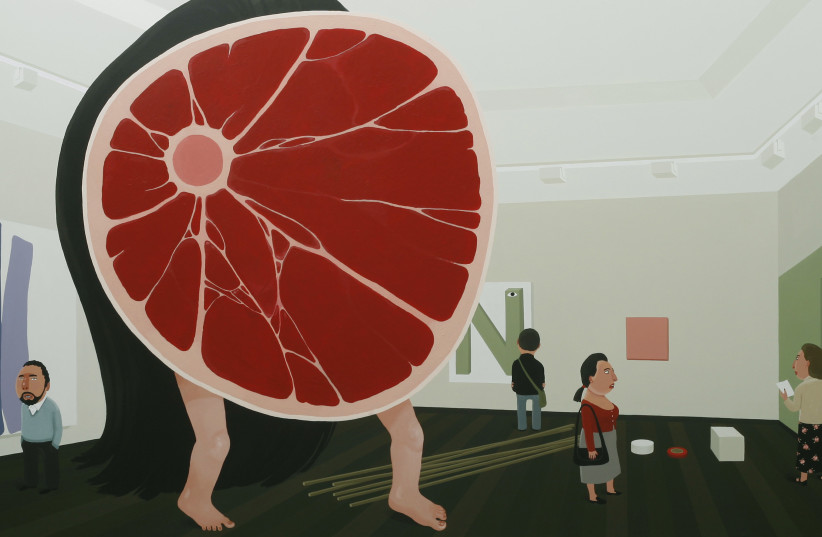

PUBLIC RELATIONS maverick Rani Rahav is able to have two conversations at the same time as he holds a cell phone pressed to one ear and a cord receiver on another. He sits next to a large painting by Cherkassky titled Fresh Meat.

Hundreds of paintings cover the walls. The face of Moshe Dayan grins from a plate painted by Tsibi Geva, Baron Samedi peers from The Back Garden by Galia Pasternak. There are dozens of old-fashioned clocks, wooden Syrian marquetry furniture, and Torah scrolls. Each piece has a neatly printed label with its title and year of production. Each Monday, an expert arrives to maintain the time-keeping machines. There is a garage with classic cars, all well maintained and ready to roll. Next to the cars, a painting by Nir Hod is hung.

“We,” Rahav and his wife Hila, “bought twenty works by Nir Hod after seeing an exhibition by him at the Ramat Gan Modern Art Museum,” Rahav said.

“We paid five years in advance with pre-written [post-dated] checks,” he points out, “and stopped going to coffee shops [to make payments].”

When they visited the studio of Lea Nikel, the abstract painter commented that she never sold works in installments before but said “never before was I approached by a couple in their 20s.”

There is also a similarly vast collection in his home, “where we put paintings on the ceiling,” he offers. He claims he and his wife never sold a single work to date.

Rahav credits the late Leah Rabin, “the wife of [late prime minister] Yitzhak Rabin who was murdered on the altar of peace,” for the passion he and Hila now have for the arts.

Red electric words blaze across a screen used in Agent of Memory, gifted to Rahav for his support of the movie. The film is a documentary about art critic (and collector) Adam Baruch, made by his children Ido and Amalia Rosenblum.

On it, the names Pinchas Cohen Gan, Yechiel Shemi, and Rabbi Ovadia Yosef make their appearance, promising to crack the code of what it means to live here in this culture, then depart.

Baruch cultivated an ascetic public persona, while Rahav encourages his employees to grab a popsicle from the office icebox. Cohen cherishes the good fortune of knowing artists and bridging Jewish-Moroccan relations. Recanati honors a promise given to a much-loved parent. These three different personalities, their interests and passions, mirror the rich diversity of art – and collecting it – in our own time.

Gates by Dina Recanati will open on Friday, June 3, at 11 a.m. at Gordon Gallery (6 Hapelech St. Tel Aviv) Opening Hours: Thursday 11 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Friday 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. and Saturday 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. Gestures – Works from the Philippe Cohen Collection is shown until Friday, May 27. Kibbutzim College of Education Technology and the Arts Opening Hours: Thursday 4 p.m. to 8 p.m.; Friday 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. 9 Ahad Ha’am St. Tel Aviv (Curator Drorit Gur Arie).