There’s nothing like being in the right place at the right time. That goes doubly for photographers who, after all, are in the business of capturing a fleeting moment in the temporal continuum and documenting it for all time.

Then again, as a sagacious Indian musician by the name of Krishnamurti Sridhar once told me, in response to my apology, when I called him for a telephone interview way past the appointed hour, “it is happening now.” In the rough and tumble of the rat race, presumably, most of us would struggle to embrace such a self-explanatory philosophy as we “try to make things happen.”

Lots of iconic images

Be that as it may, Allan Tannenbaum was certainly around at several pivotal junctures of Western cultural history to snap some A-lister artists and provide us with a slew of iconic images.

The celebrated 78-year-old photographer recently popped over from the States to attend the opening of the new Untitled exhibition of works by Keith Haring, at the Arena venue in Herzliya. Haring, who died in 1990 at the age of 31, was an American artist who emerged from the New York graffiti counterculture of the 1980s and gained fame for his pop art street creations.

We have some idea of how Haring went about his work thanks largely to Tannenbaum’s evocative frames of the painter in full creative flow in his studio, and at various locations around the Big Apple.

Tannenbaum said he was delighted to have an opportunity to return to these shores, after a 25-year hiatus. He jokingly noted that “Tel Aviv has turned into a Manhattan skyline” but, on a more serious note, he expressed his happiness at being instrumental in introducing the Israeli public to the various facets of Haring’s oeuvre and character. “I’m here representing him, I’m representing his spirit, I’m representing the connection to that era,” he says. It was a good time to be around.

“That was a wonderful era in New York City, so full of creativity,” Tannenbaum recalls. “I feel that’s my mission, being here [in Israel] right now.”

The reference to the present moment has been a feature of the photographer’s work for many years now. I noted his shot of British punk rock band Sex Pistols’ bass player Sid Vicious being led away, in handcuffs, after his girlfriend Nancy Spungeon’s body was removed from the Chelsea Hotel in October 1978. I wondered whether that was a sixth sense you develop, or a gift you are born with. “I guess it’s a knack. It’s nothing you can go to school for, or take a photography lesson for,” he smiles. “It comes with practice, I guess.”

Practice and talent

Practice does tend to veer towards perfection. But you also need to have the propensity for putting in the graft, and also getting out and about. “I’m a very curious journalist,” he states.

Tannenbaum has put in the hours on the beat. “My start in professional photography was working for the SoHo News,” he says, referencing the alternative weekly paper put out in New York between 1973 and 1982. Back then the art scene was jumping and jiving, as the hippie generation evolved into a more savvy scene, and music and visual arts took on a grittier less ethereal ethos.

More importantly, at least in technical photography terms, this was long before the digital camera age, when you couldn’t just merrily snap away hoping that one frame out of dozens would provide the desired end product. And you had to wait before you got into the darkroom, or get your prints back from the developers, before knowing what you’d actually caught.

I put it to Tannenbaum that, had he gotten into the scene now, with the plethora of technologically advanced features out there at our beck and call, he might not have developed that sixth sense of knowing just when and where to snap.

“Maybe not, because there’s this constant sensory and information overload. Instead of trying to find things you would be flooded with them. So, how would you pick out what you should be doing, what would be good?”

Back in what he calls those “more innocent times,” there was more room for maneuver in a less-crowded playing field.

“Part of the thing was to have something unique, and not have what everybody else has. Now, if you got to an event or something is happening spontaneously, everybody there has their cellphone camera, and it’s instantly there at the same time.”

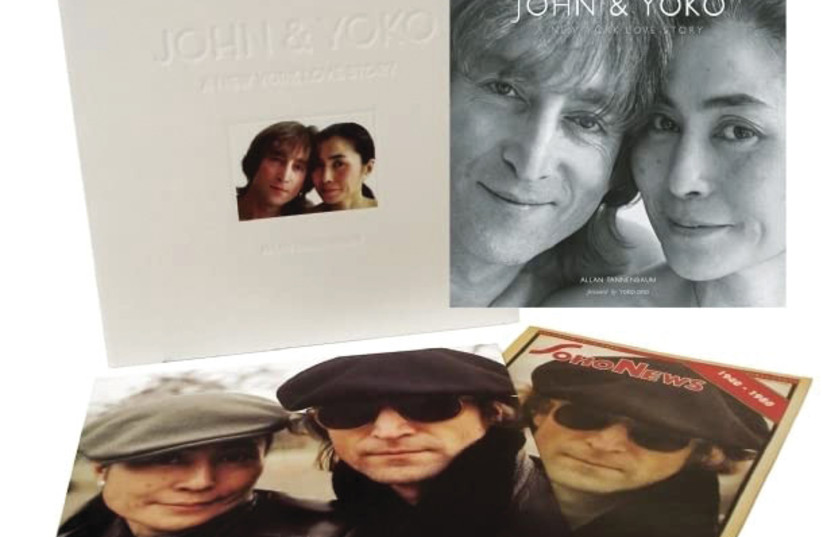

Timing is, naturally, of the essence and Tannenbaum was, certainly on the spot in timely fashion – apologies to the aforementioned Indian gent – in 1980. In November of that year he was asked to take pictures of John Lennon and Yoko Lennon in the lead up to the release of their new album, Double Fantasy. This was after the couple had spent five years as virtual recluses. Tannenbaum snapped them at various locations, and also took romantic nude shots of them which, of course, required a great deal of sensitivity in addition to technical acumen.

He showed Lennon some of the contacts and was about to go over to the couple’s Dakota apartment in New York on December 8, with prints, when his editor dropped by and told him Lennon had been shot. Tannenbaum says he was stunned by the news.

The death of John Lennon

“It was just something that you couldn’t believe,” he recalls. “I was in the darkroom making prints to bring to them. I had seen John a few days before, showing him pictures I had done on November 21 and 26, especially the intimate photos.” Tannenbaum had clearly done a good job and got the deserved kudos. “John told me that he loved them because I made Yoko look so beautiful. I really had a connection with John.”

For myself and the rest of my generation, who grew up with the Beatles, Lennon’s death signaled the end of something, and put paid to any flickering hopes that the Fab Four might still get together for a last hurrah. Besides his personal loss, Tannenbaum wonders what Lennon might have put out over the years.

“I presume we would have continued to collaborate, because he felt comfortable with me. When you think about what may have been created, for all these years after that, in terms of his music, his art and his writings, film work, everything that would have continued, it is an unimaginable loss to the whole world.”

Lennon left us far too early, at the age of just 40. But Haring died even younger. Not quite members of the infamous “27 club,” of artists like Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Kurt Cobain, but their passing was untimely in the extreme.

I was reminded of Mr. Sridhar.

“You have to be in the moment,” Tannenbaum concurs. “One never knows what’s going to happen.”

The artists may have gone their way but, like Haring, at least they have blessed us with the works they managed to create during their time on terra firma.

“I felt it was something special at that moment, although I had no way of knowing if it would stand the test of time,” Tannenbaum observes about Haring’s legacy. “There were a lot of fads in the art world. But it certainly has stood the test of time, greater than my wildest imagination.”

And now part of that is on show here, in no small part thanks to Tannenbaum’s gift and ability to know just where and when to snap.

Untitled closes on June 30.

For more information: https://www.keith-art.co.il/