"The trauma is passed along in silence... It was always there and it was never told to us. I had to guess. I had to invent.”

Acclaimed Israeli cartoonist Michel Kichka was describing the movie adaptation of his graphic novel My Father’s Secrets in a recent interview.

What is the film about?

My Father’s Secrets tells the story of Kichka’s youth as the son of Henri Kichka, a Belgian Auschwitz survivor, in the 1960s. It opens throughout Israel on April 20 and is being shown at the Jerusalem and Tel Aviv Cinematheques on Holocaust Remembrance Day on Monday night and Tuesday.

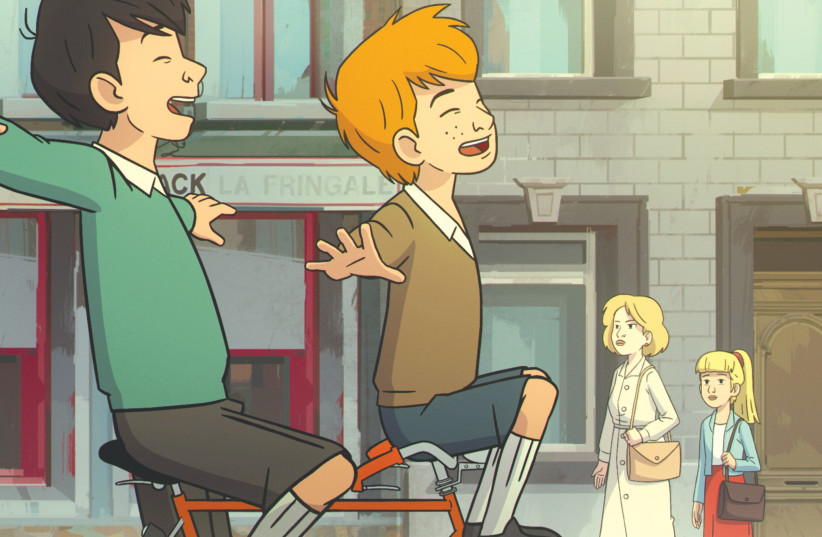

In this appealing movie, which is suitable for tweens, Michel is a mischievous aspiring artist more interested in girls than school, who loves and is annoyed by his adorable little brother, Charly, who tags along wherever he goes. Michel also has a demanding mother and two very assertive sisters but it’s his relationship with his father that is complicated. Michel sees the number on his father’s arm but knows he is not supposed to ask about it, although Charley does and is told to be quiet.

But Michel is fascinated by his father’s early life and sneaks into his study where he finds a wealth of clippings about the death camps and sees his father’s own drawings of his years in hell at Auschwitz. Although his father will occasionally sit with him and draw rude caricatures of Hitler, he will not say a word about his own life. Eventually, the father becomes a leading speaker, at first in Belgium and then all over the world, bearing witness to Nazi crimes but at home, he is as tight-lipped as ever.

MICHEL IS going through adolescent rebellions and growing pains, just as a sudden tragedy jolts the family, tearing Michel and his father even further apart. Eventually, long after Michel moves to Israel and starts a career as an artist, their rift is healed.

Kichka, a charming, soft-spoken man, was interviewed via Zoom from his studio and joined by Allan Greenblatt, one of the movie’s producers. Kichka said that the story of both the novel and the movie was very much autobiographical. “I have heard from many people of my generation that they didn’t hear the story of the parents from their parents... And that’s true throughout the world that wherever people suffered great traumas, that’s the universal dimension of the story. There is the feeling that you protect the children if you don’t tell them. But we understand, it doesn’t protect them.”

Said Greenblatt, “He told a family story, showing how the people in the family – the children, the parents, everyone – are affected and I can relate to that because both of my parents survived Auschwitz and when I saw this movie and when I understood what they were trying to do, I immediately had to come aboard.”

The movie was directed by Vera Belmont, a French director known for such films as Red Kiss and Surviving with Wolves, who adapted the screenplay from Kichka’s novel with Valerie Zenatti. Belmont seemed to Kichka to be the perfect person to bring his book to the screen. “What Vera saw [in the book] was the opportunity to tell the story. Allan is the second generation and Vera Belmont was born then, she was a little girl... whose parents were Communists in the Resistance. She felt that the movie was part of her story and the story of our people and of the world. And she did a wonderful job. I’ve seen the movie 10 times and every time, I get emotional.”

Noted Greenblatt, “If somebody says ‘Shoah’ and ‘animation’ they seem like two opposite sides of a coin but if they filmed this in live action, it wouldn’t have achieved what this already achieved. It is so right to do this in animated form.”

Kichka agreed. “I think that children don’t want history lessons. They want family stories. That’s what the film does.”

In order to reach a young audience, Kichka understood that changes must be made and he gave Belmont and Zenatti free reign to adapt his book. “So that the movie could be shown as a family movie... it had to be reimagined freely as a script. Much of what happens in the movie is a very intelligent adaptation of the book. It’s suited to its audience... so they can laugh and cry and identify with the characters in a way that is appropriate.” But the essence of his novel is intact on screen: “The emotions that a mature reader experiences when reading the book are the same emotions that a young audience experiences when seeing the movie.”

There are versions in French and English

THERE ARE versions both in French and English and in the English language version, Henri Kichka is voiced by Elliott Gould.

“For the young, the Holocaust is the last century, that is maybe connected to their grandmother and grandfather. It’s in the distant past. But many of the readers of the book are my age, approximately 50, 60, 60+. The book talks about something they are familiar with but young audiences are not familiar with it. So Vera Belmont added clips from the Eichmann trial in the movie. It was a strong decision. Many children, for example in Israel and in every country where the movie is screened, it’s the first time they have seen this trial... So even if the movie is animated, it’s true and it’s concerned with true events.

“After the film is done being shown in theaters, it will be available to educators to show in schools... Because of the animation, the gentleness, the colorfulness and the humor – and there is humor in it – it’s not scary to approach it and people engage with it and ask questions. I’ve been to many screenings in France and Belgium and children asked questions about it. It fascinated them.”

The process of writing the novel and now of seeing it made into a movie has been cathartic for Kichka, just as writing a memoir about his wartime experiences was for his father. “One of the insights I had while working on this book was that for my father, when he started to talk about his experiences, he rebuilt himself. It was a process of reconstruction and a way for him to reclaim the human dignity that he was robbed of there... I’m aware of the parallel process of both of us writing our books but my father’s book is a book of testimony and my book is a creative work.”

At several points during the interview, Kichka seemed overcome by emotion, as if he were fighting back tears. “After the book, I’m not the same person I was before the book. The creativity [of writing it] freed all the difficult feelings that existed... It put them all in the light of day, it made them accessible and now they will become accessible to viewers through the film and it’s a process of healing. I feel it was very meaningful work that I did for myself but it was also meaningful for other people and now through the movie, it will be seen by many more.”