Ben-David lives and works in London and over the past decade lived in Portugal as well. He represented Israel at the Venice Biennale in 1988. His works are exhibited in museums and art galleries across Europe, Australia, America, Central Asia and the Middle East.

In this exclusive interview with the Magazine, Ben-David talks about his artistic processes and his early life experiences, including being a soldier during the Yom Kippur War.

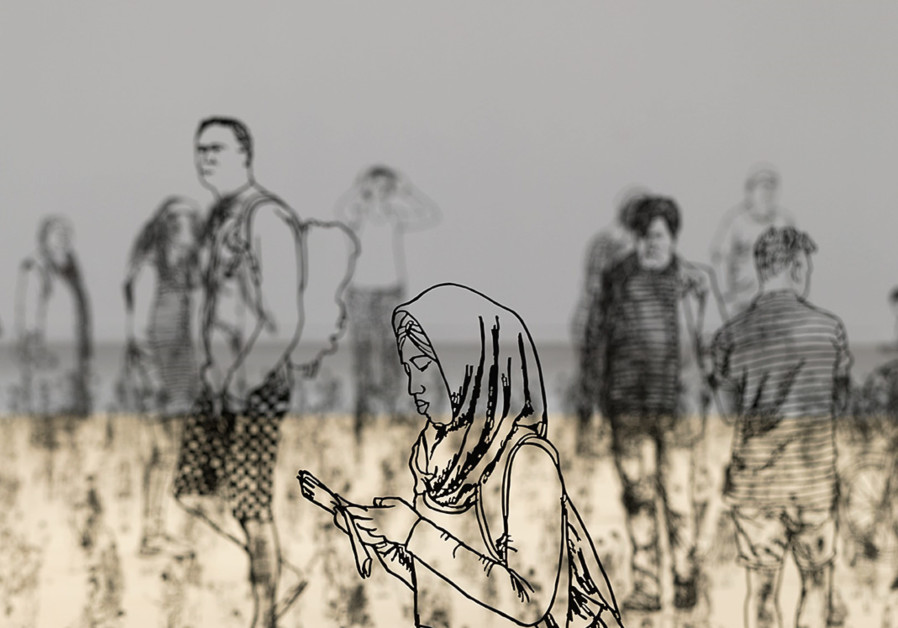

I don’t have a chance to look at people when I am walking. People are also not aware that I am taking photos. I have a flat screen. When I click the button I turn my head away. This way they have the best expressions without posing. This is very important to me, because when I draw, I want to get the feeling of that moment.

The metal itself doesn’t attract me at all. I am not interested in the material itself. I am interested in the image, and metal now is helping me to implement my ideas in the most spontaneous and the quickest way.

My assistant works on computer on my drawings, adding bases, checking that all lines are connected. I trained my assistant to cut the aluminum ones. But I cut them myself quite a lot in the past. For example, two thirds of Evolution and Theory, 250 items, some of which reached up to three meters, were done by me. It took me over two years until I realized I could have an assistant.

In 2005 I won a prize at the Tel Aviv Museum, and part of the prize was this sculpture. I don’t know if people should start from it. Maybe. Regarding the technique, you can see there my attempts to create the thin line figures in one boy in this sculpture. But I was not there yet. I had to find the way to show this kind of space, as I do now.

Yes, for example, when I had this exhibition in Krasnoyarsk, Siberia, two years ago, there was a big bronze statue of Lenin at the museum. I was asked if they should cover it with something, but I decided to keep it. So this big sculpture of Lenin with his company was behind my installation. Some people said that Lenin is looking at the masses. In every country, people are giving a different interpretation to my art. In Israel some people see a connection to the recent events, the war in May.

I think in a way it hit our time.

For Jews, the significant number is six million, but no, there is no connection to it. The first time it was shown in 2016, in Sydney, there were 2,000 figures. After that, the installation was shown in Los Angeles, Seoul and Portugal. When I started it, I set a goal to make 10,000. Quite ambitious. But this is just a number. I don’t know if I will make less or more.

This is a really good question. The tallest one I did so far was 10½ meters. The process of my work is like this: When I make a miniature, immediately afterwards, I feel I want to make something large. For instance, as soon as I did the sculpture of this big tree that contains figures for Yad Vashem [For the Tree of the Field is Man’s Life, 2003], I had an instant desire to create another sculpture of a body that contains trees inside. There is that constant desire for duality in me. I have always felt that I want to explore the other side.

This was one of my ecological installations. The notion of what beauty is and what is unattractive to us. The idea was that one enters the room and sees a circle full of butterflies and wings around people. On the other side there are just insects and cockroaches.

Yes. That kind of insect I replace with the human body.

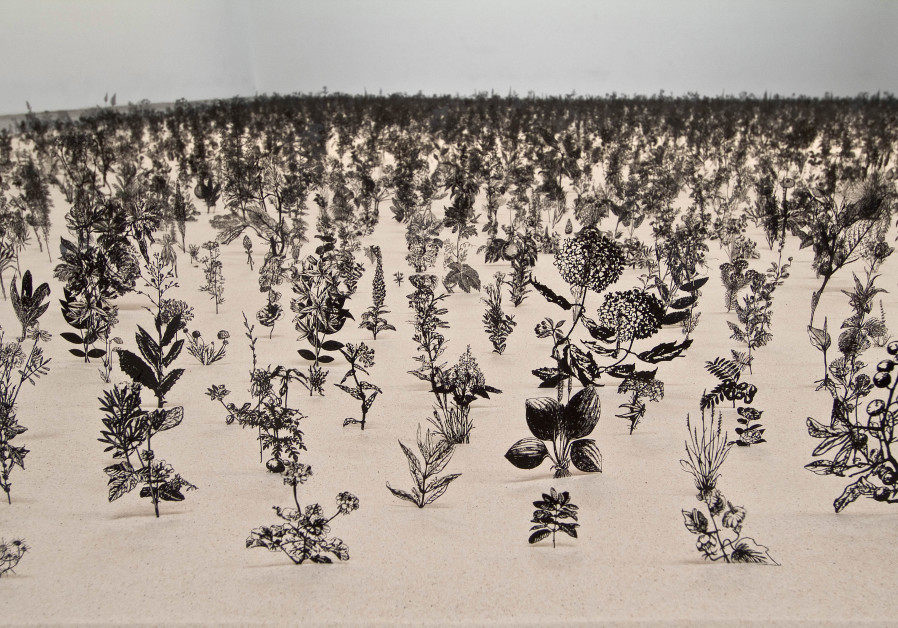

The common aspect was the sand on the ground and lots of elements. In 2007, when I started Blackfield in Vila Nova de Cerveira in Portugal at one of the oldest Biennales, I showed only 1,500 flowers. I didn’t even know it was a competition and I got the Grand Prix in the Biennale 2007. In the Tel Aviv Museum, two years later, there were 20,000 elements. Now I have 30,000. But these are technical things. The content of these exhibitions is different. I don’t know much about flowers. I know maybe 10 kinds, but I was interested in the meaning. They are given to us in the saddest and happiest moments of life.

If you see the black flowers, one can feel sadness, but I end it with many happy colors. To me, flowers are the metaphor of our life. We can move from one, extend to another.

I am not working for someone else to understand my ideas, I am working for myself. I try to express myself. I am very happy when people can see what I see. But I am also happy when people notice something I did not see. I can learn something from it.

I wanted to be a painter. Unfortunately, I was not accepted to Bezalel [Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem]. Then my father, Moshe Ben-David, who was already a well-known jeweler in Israel, pulled some strings and asked some people at the academy to at least see my works, and I got accepted. I will never know if they really liked my works or if it was because of my father. After a few months, they told me I was better than they thought, but regardless, at the end of my second year I was kicked out of the school.

Why?

I don’t know.

A friend of my father once told me that if I ever got interested in sculpture, I could be his assistant and study in England. So years later I did it. I was planning to go in 1973, but there was the [Yom Kippur] war in October, and I was stuck in the Suez Canal with my troops.

So I went to England only in April ‘74. I worked with him for three months. Then I felt the need to go back to school.

Not really. In general, when I came to England it was a culture shock for me. I couldn’t understand the accent, and the different environment overwhelmed me. I felt like an alien.

By the way, when I was entering the UK, I had to fill out a form, and there was a question: “Are you an alien?” instead of the word foreigner. So anyone who was not English was an alien, from another planet.

I studied for a year at the university. Then I was accepted, as an exception, to the famous St. Martin’s School of Art, despite not having a BA degree, and I graduated in advanced sculpture studies. A few years later, I was teaching there, even though my English was still not so good. A funny story: My teacher from Bezalel was later my student at St. Martin’s.

I pushed everything in. I didn’t let it affect me emotionally. I was lucky enough to be in the war, but to see the war passing by me.

I was not involved in it by fear. I was also not doing any stupid heroic things, and all that nonsense. I just did everything I was asked to do. When I look back now, I was in one of the most dangerous places on the Egyptian front. I was at the bridge, I had to throw a grenade every half hour. The place was bombed by the Egyptians. Together with four other soldiers, we were detached from the rest of my unit for about four weeks. We rejoined everyone at Suez City. It was quite an experience. I was drawing in the army, even during those difficult times.

No, only the people from the past five years.

Yes, it was a big outcry among local artists, because for the first time in Israel, there was an artist selected who did not live in Israel – already 14 years. To other countries, it was acceptable for artists to live all around the world, but in Israel it provoked a national discussion about it, even in the Knesset. So it opened up a definition of being Israeli.

First of all, it makes me happy to hear it. Back in the 1980s, my work usually contained two elements: one – a form, nature, and another from design. Initially I was always interested in the theory of evolution and I wanted to make a sculpture of evolution. But I was told, “We can see you haven’t lived here for a while. There are religious people here, nobody will ever accept it,” so I stopped at the monkey. The name of the sculpture came after, because there was the Shabbat line [the eruv], the limit of the city, so I named it Beyond the Limit.

I have shared my time between London and Portugal for the past 10 years, and I spend half a year traveling with my exhibitions to other places. But I feel most at home in Israel.

Relatives and friends. I have some friends I have known since we were six years old. Also the army. You have with these people a common goal: to survive. It makes the bond stronger. Also, childhood in Israel is very short, teenagers here become adults faster. I remember when I started teaching in London, my students were 20, 21 years old. They were very mature when they talked about their artwork, but moments later they were running around and throwing clay at themselves, like kids. At that age in Israel, you were shooting bullets.

I was born in Beihan, Yemen, in 1949, but my parents moved to Israel when I was five months old. We went through all the immigration processes: camps for new immigrants, tents. And what I remember is that cheap wooden houses were an upgrade from tents.