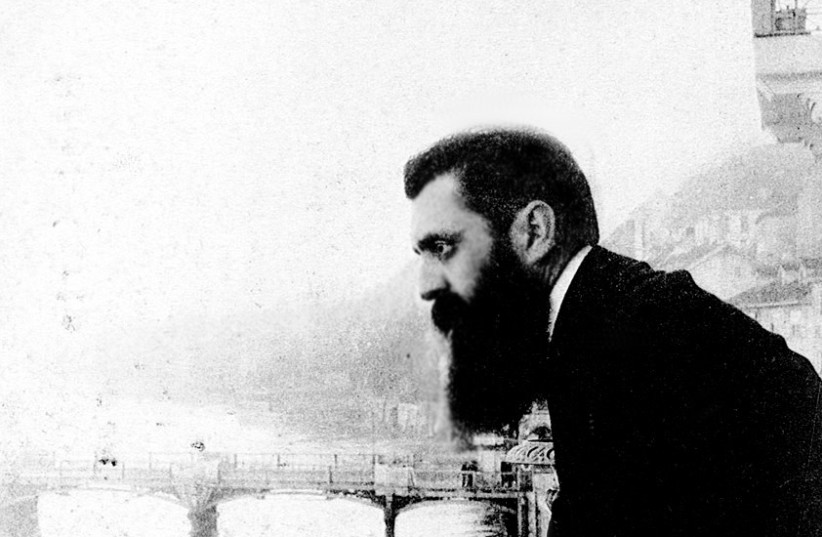

The yahrzeit of Theodor (Binyamin Ze’ev) Herzl falls on the 20th of Tammuz. Each year, on that day, a group of haredi and Orthodox Zionist Jews gather at his grave on Har Herzl to pray and say kaddish in his memory (Yishai Friedman, Makor Rishon, July 17, 2018). The goal of this gathering is to right a sad historical wrong.

In its early years, the Zionist movement was viewed with a great deal of suspicion in some haredi circles, partially because many of the new social and political movements of the time, like the Enlightenment, socialism, communism, etc., had led some Jews to abandon traditional Judaism.

The new, political, Zionist movement, which was attributed to its secular founder Theodor Herzl, was no different from the perspective of many haredi rabbis and leaders who were contemporaries of Herzl. Here are several pertinent examples:

The old slogan of the great Rabbi Moshe Sofer (Chatam Sofer), “What is new is biblically forbidden,” was invoked. The Balfour Declaration, issued by the British advocating for a state for the Jewish people in Palestine, was ridiculed in a homophonic way by Rabbi Chaim Elazar Shapiro (1868-1937), the Munkaczer Rebbe, as the “Ba’al Pe’or Declaration” (Ba’al Pe’or being the idol from biblical times that was worshiped by human defecation).

Furthermore, the Bible (Numbers 15:39) warns that we should not follow our hearts and our eyes to commit sins. The Yiddish word for heart is hertz, and the Yiddish word for seeing is kuk. Hence, it was said that it is a biblical commandment, “Do not be led astray by Herzl or (Rabbi) Kook.”

Other haredi rabbis were also wary of Herzl’s Zionism. Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik (1853-1918) of Brest-Litovsk, a contemporary of Herzl’s, warned about the dangers of Zionism to religiously observant Jews (The Rav II, Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkopf, page 112).

Chabad Rebbe Shalom Dov Ber Schneerson (1860-1920) fought fiercely against Herzl’s Zionist movement. In 1903, he published Kuntras HaMa’ayan, which rejected the Zionist movement in strong terms.

He was the first to quote the “three oaths” (Ketubot 111a) imposed on the Jewish people not to return in big numbers to recapture the Land of Israel by force. He saw the Zionist endeavor as doing just that. This argument was the central point of the Satmar Rebbe, Yoel Teitelbaum (1887-1979), in VaYoel Moshe – Ma’amar Shalosh Shevuos) a half-century later.

The chief rabbi of the haredi Ashkenazi community in Jerusalem, Rabbi Joseph Chaim Sonnenfeld (1848-1932) called the Zionists “evil men” and said that “Hell had entered the Land of Israel with Herzl.”

Rabbi Raphael Breuer (1881-1932) of Frankfurt, a grandson of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, had strong anti-Zionist leanings. He wrote the following about religious Zionism (quoted in Tobias Grill’s article, “Jewish Anti-Zionist Movements”): “So, in Zionism, too, religion plays the role of the old mother-in-law who one has to respect, yes, treat kindly, but in moments of discontent, one would like to beat to death.”

Rabbi Elchanan Wasserman (1874-1941) declared:“The nationalist concept of the Jewish people as an ethnic or nationalistic entity has no place among us, and it’s nothing but a foreign implant into Judaism; it is nothing but idolatry. And its younger sister, ‘religious nationalism,’ is idol worship that combines God’s name and heresy together.”

IN CONTRAST to all these negative sentiments about the Zionist movement, there were rabbis who advocated the return of world Jewry to the Land of Israel before Herzl came on the scene.

Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer (1795-1874), was a German Orthodox rabbi. In his Derishat Tziyon, he advocated that there is a religious mandate to settle the Land of Israel, to build homes and engage in agriculture, thereby providing an income for the many impoverished European Jews who would immigrate.

Because of Rabbi Kalischer’s lobbying efforts, the French Alliance Israélite Universelle founded the Mikveh Israel agricultural school in the Land of Israel in 1870.

Rabbi Yehudah Solomon Alkalai (1798-1878) may have had an indirect impact on Herzl. Herzl’s paternal grandfather, Simon Loeb Herzl, reportedly attended Rabbi Alkalai’s synagogue in Semlin, in today’s Serbia. The elder Herzl got hold of Rabbi Alkalai’s 1857 work advocating the “return of the Jews to the Holy Land and the renewed glory of Jerusalem.”

Contemporary scholars conclude that his grandson’s implementation of modern Zionism may have been influenced by that relationship. (Theodor Herzl: A New Reading by Georges Weisz).

On a personal note, on a trip we took to Eastern Europe in 2018, we drove from Warsaw to Lithuania. On the way, we stopped in Bialystok to visit the Beit Midrash of Rabbi Shmuel Mohilever (1824-1898), a graduate of the Volozhin Yeshiva and a founder of the Hovevei Zion movement, who became the rabbi of Bialystok in 1893.

In 1897 he forwarded a statement to the first World Zionist Congress in Basel. He urged that those who love Zion should work in harmony, despite differences of opinion and religious practice.

Rabbi Yitzhak Reines (1839-1915), a younger colleague of Rabbi Mohilever’s, joined him in proposing a Palestinian settlement that would combine Torah and labor. Rabbi Mohilever used the term, mercaz ruchani (religious center), which became the acronym, “Mizrachi.” In 1901, Rabbi Reines chose Mizrachi as the name of the new religious Zionist movement he founded.

Once Herzl made his proposals for the establishment in Palestine of a Jewish state, questions arose about the place of the Jewish religion in Herzl’s Zionist vision. Walther Lacquer (A History of Zionism: From the French Revolution to the Establishment of the State of Israel, page 410) wrote this dramatic account:

“On the final evening session of the [First World Zionist] Congress, Arthur Cohn, the 35-year-old Orthodox rabbi of Basel, gave his address.

“He received, according to the official minutes, ‘a thunderous welcome.’ Rabbi Cohn praised Herzl, declaring that ‘his heart swells with deep emotion’ after hearing his speeches. But Cohn also expressed his concern that ‘if the Jewish state were to arise now, its party leadership, which we know does not honor [religious Jewry’s] views, would attack the Orthodox.’”

In contrast, one of the great leaders of haredi Vilna saw Herzl in an incredibly positive light. Rabbi Shlomo Hacohen (1828-1905), author of the Cheshek Shlomo and leader of haredi Vilna, demonstrated this not only in words but in action. In 1903, Herzl stopped in Vilna on his way back from meeting the czar in St. Petersburg.

Haredi Vilna greeted Herzl in a dramatic gathering. Wearing his Sabbath finery, Rabbi Shlomo Hacohen blessed Herzl with the Priestly Blessing, and presented him with a small Torah scroll. He declared, “A king must have a Sefer Torah!” (Deuteronomy 17:8).

Zev Yavetz (1847-1924), the historian, and Rabbi Yoel Herzog (1865-1934), the great-grandfather of Israel’s current president, Isaac Herzog, were present at that event. Yavetz wrote an inscription for Herzl. The ark that contained the Torah is on display today in the Herzl Museum in Jerusalem. Unfortunately, the Torah scroll has been lost.

Rabbi Hacohen is quoted as saying, “Were Herzl someone who ate kosher, I would have said that he was the king Messiah!” (Moshe Nachmani, Lev Ha’umah, pp.184-191, 263).

THIS WEEK we are in the midst of celebrating 74 years of the State of Israel. Israeli flags festoon many buildings, and cars featuring the flag of Israel blowing in the wind are ubiquitous!

In the US, no one has ever witnessed a Memorial Day where an entire nation grieves for its fallen heroes. Though barbecues are certainly a feature of American Independence Day celebrations, the joy and revelry that characterize the 5th of Iyar are not only festive and fun, but also deeply moving, emotional and appreciative.

Even after 74 years, the Jewish people can still remember the tragic events of the Holocaust, which gave rise to the establishment of the modern state. The survivors who told their stories at the official Remembrance Day commemoration at Yad Vashem last week, and other survivors we are lucky enough to have in our midst still, bring home the vital importance and indispensability of the State of Israel to the Jewish people the world over.

Orthodox Jews have a lot to reflect upon when Remembrance Day for the Fallen of Israel’s Wars is commemorated, and Independence Day is celebrated. As we have recorded, there surely was a legitimate debate among Herzl’s contemporaries about the enormous and ambitious project that he launched but did not live to see to fruition.

That debate continues until this day. It is fair to say that the haredi world has come a long way in coming to terms with seeing the State of Israel in a positive light. Today, there are haredi units in the IDF, haredi heroes among the fallen, and in general, a deeper appreciation of the ultimate value of the independent State of Israel to all Jews.

May we all merit to continue celebrating a strong, vital, ethical, united, independent Israel!

A new oleh, Heshie Billet is rabbi emeritus of the Young Israel of Woodmere and a member of the US President’s Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad.

A new olah, Rookie Billet recently retired from a long career as a Jewish educator, principal, synagogue rebbetzin, and halachik adviser in the US, and hopes to contribute to life in Israel.