“The best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry,” wrote Scottish poet Robert Burns more than 200 years ago. Such is the case with the following review of the Shakespeare Haggadah, which was scheduled to appear before Passover. Unfortunately, this writer’s ill-timed spill on a rainy Shabbat afternoon and subsequent knee surgery precluded the possibility of this review from appearing until now. Nevertheless, as the Bard of Avon himself wrote, “Better once than never, for never too late.”

While earlier generations had a relatively small number of English-language Haggadahs at their disposal, recent years have witnessed a proliferation of all types of Haggadahs in English. There are scholarly Haggadahs, humorous Haggadahs and political Haggadahs.

A quick perusal of the selection available on Amazon illustrates the wildly disparate listing of popular versions currently available, including such unlikely titles as the Hogwarts Haggadah, the Curb Your Haggadah for fans of the Larry David comedy series, and the 30 Minute Seder Haggadah, for those who are in a hurry, alongside more traditional works.

The Shakespeare Haggadah is the creation of veteran freelance writer Martin Bodek, who has penned other light-hearted Passover works, including the Emoji Haggadah, the Coronavirus Haggadah and the Festivus Haggadah. The Shakespeare Haggadah is his first work that includes both the Hebrew and English text of the Haggadah on facing pages.

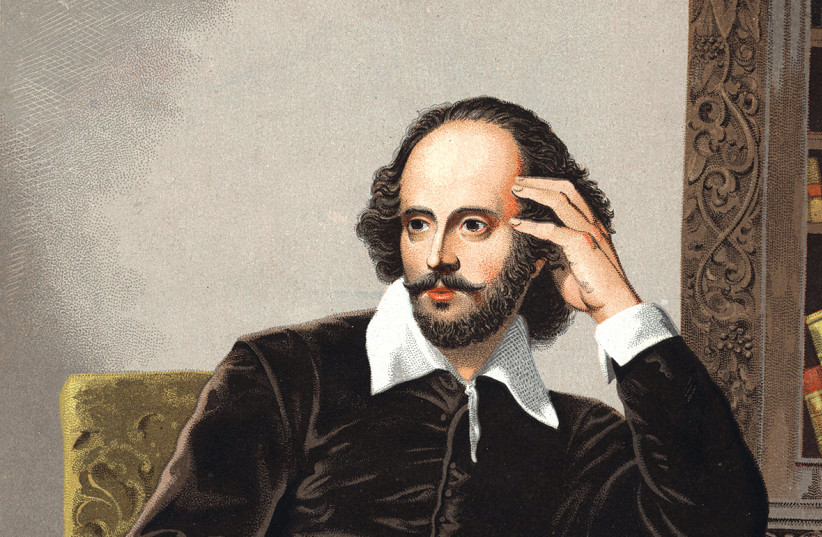

Apart from the etching of Shakespeare holding a glass of wine in one hand and a matzah in the other, what makes this 192-page Haggadah relevant for Shakespeare aficionados? Bodek’s goal, as he outlines in the book’s introduction, was to weave as many quotations from Shakespeare’s works as possible into the English translation. The Shakespeare Haggadah includes 433 citations and references from the Bard’s famous and less-famous works sprinkled throughout the text. In addition, every play written by Shakespeare is cited no less than five times in the book’s footnotes.

References to Shakespeare’s works begin on the very first page of the book, which includes a drawing of the Seder plate, including “roasted egg in wrath and fire” (Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2), “parsley to stuff a rabbit” (The Taming of the Shrew, Act 4, Scene 4) and “the enchanted herbs” (The Merchant of Venice, Act 5, Scene 1). The English text of the Haggadah is displayed in a Shakespearian-style font, evoking the typeface of the time.

For the most part, Bodek combines quotations from Shakespeare with the English translation to make a cogent, understandable whole. For example, he translates the “Ha Lahma Anya” section– “This is the bread of affliction” – that is read prior to the Four Questions, as follows:

“This is the Bitter Bread of Banishment

The vaward uncovers the unleavened bread, raiseth the Seder plate, and sayeth out loud:

This is the bitter bread of banishment that our ancestors consumed in the land of Egypt. Anyone who is filthy famished should cometh and consumeth, anyone who is in need should cometh and by and by thy bosom shall partake of the Passover sacrifice. Now we art hither, next year we wilt beest in the Land of Israel. This year we art slaves, next year we wilt beest free people.”

In the above translation, Bodek artfully includes references from Richard III (“The Bitter Bread of Banishment”), Henry IV (“filthy famished”) and Julius Caesar (“the bosom shall partake”).

Later in the Haggadah, in reference to a quotation from Richard II, which mentions “holy clergymen,” he titles the famous story of Rabbi Eliezer, Rabbi Yehoshua, Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah, Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Tarfon, who met in Bnei Brak as the “Story of the Five Holy Clergymen.”

The Shakespeare Haggadah is a clever attempt to merge the works of Shakespeare with the Haggadah. Some may find it sacrilegious, but I would venture to say that devotees of Shakespeare of all ages will find it interesting and will hunt through the English translation looking for Shakespearean references.

The Hebrew text is serviceable, though I found several minor errors in it. Bodek sprinkles humorous instructions throughout the Seder text, which may entertain some readers.

BEYOND THE Shakespeare Haggadah, the question regarding the relationship between William Shakespeare, the Jews and antisemitism is a more serious subject, which scholars have discussed for many years.

Shakespeare was born in 1564 and died in 1616. At the time of his birth, Jews had been banned from living in England for 274 years – since 1290, when King Edward I had barred any Jewish settlement in his kingdom. They were not permitted to return to England until 1656, under Oliver Cromwell’s rule.

Did Shakespeare know of any Jews?

Despite the ban on Jewish settlement in England, Jewish communities did exist in secret in London and other cities during Shakespeare’s lifetime. Did he know any Jewish people? It is difficult to say.

While Jews are mentioned in some of his plays, Shakespeare’s best-known play dealing with the Jews is, of course, The Merchant of Venice, in which a Venetian merchant named Antonio defaults on a loan provided by Shylock, a Jewish moneylender.

Scholars have debated the antisemitic overtones of the play, reflected in Shylock’s demand for “a pound of flesh,” as opposed to his later pleas for mercy that evoke the universal nature of humanity, when he states, “I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh?”

“I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh?”

Shylock

Sadly, the Merchant of Venice had become a favorite in countries where antisemitism had taken root. Between 1933 and 1939, more than 50 performances of the play were held in Germany.

The Shakespeare Haggadah is an admirable effort to incorporate the literary genius of perhaps the greatest writer in the English language with the Haggadah’s timeless text. While some may find it a bit frivolous and overly cute, devotees of Shakespeare will enjoy it, and it may even encourage a more serious study of antisemitism in Shakespearean England.

THE SHAKESPEARE HAGGADAH

By Martin Bodek

Post Hill Press

192 pages; $17