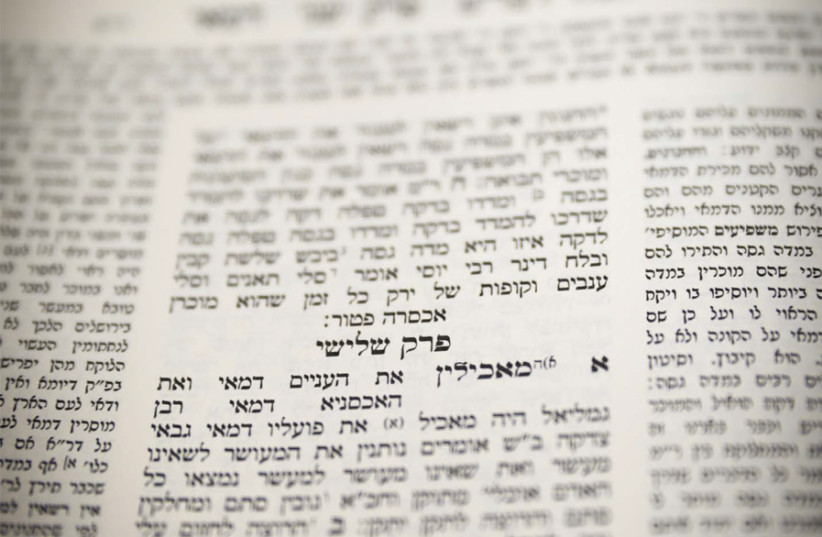

Anybody who has ever learned Daf Yomi – a daily page of Talmud study spread over 7½ years to complete the entire Babylonian Talmud – has experienced moments of jaw-dropping serendipity.

This happens when the day’s page under scrutiny aligns with specific holidays or mitzvot.

When, for example, the page being learned a week before Passover deals with the Passover Seder. Or when the pages learned during Sukkot deal with what constitutes a kosher sukkah.

When this happens, when the page being learned coincidentally is relevant to a particular holiday or mitzvah to be performed at that moment, it can make the study more meaningful and may imbue the holiday and mitzvot with greater meaning.

Daf Yomi serendipitous moment

Learning Tuesday’s daf (Hebrew for a sheet or page) was one of those serendipitous moments; indeed, it was a Daf Yomi serendipitous moment par excellence.

While over 7½ years it is statistically probable that the page being learned will coincide with moments on the Jewish calendar, Tuesday’s Daf – Gittin 56 – went beyond mere alignment with the calendar. It intersected with Israel’s headlines.

Gittin 56 intersected with the Jewish calendar by recounting the events leading to the destruction of the Second Temple precisely during the Three Weeks – the semi-mourning period leading up to Tisha Be’Av in two weeks, the date when both the First and Second Temples were destroyed.

And Gittin 56 intersected with the headlines because its themes – the dangers of baseless hatred and zealotry – mirror contemporary events unfolding in this country. One could not study Gittin 56 on Tuesday and then watch the live broadcasts of the debate in the Knesset’s Constitution, Law and Justice Committee and the protests in the streets on this “Day of Disruption” without sensing bone-chilling and unmistakable parallels.

At the very end of the previous daf, Gittin 55b, the Gemara jumped into the topic of the war waged by the Romans against Judah by seeking to understand the following verse from Proverbs: “Fortunate is the man who always fears [the consequences of his actions]; and he who hardens his heart will come to harm.”

According to the elucidation in the Schottenstein Artscroll edition of the Talmud, this verse is illustrated in the Gemara by three episodes in which tragedy struck because people failed to consider the consequences of their actions.

In each of these episodes, a note to the text reads, “people acted recklessly, complacently assuming that their current state of relative peace and prosperity would continue. They failed to consider that... their fortunes might change for the worse.”

When reading these words, it is impossible not to draw parallels to the country’s current situation. For instance, the government’s shortsightedness in launching the judicial overhaul bill without considering the backlash this would trigger and the damage it would cause to the country’s economy, international standing, and security. And the opposition and protest leaders’ lack of foresight in setting precedents with far-reaching consequences: for example, from this time onward all those with a grievance will feel completely justified in promoting their cause by shutting down the country and threatening not to show up for reserve duty.

Neither side seems to be fully aware of the potentially disastrous consequences for the country of their actions.

The first episode in Gittin 56 to illustrate the idea that tragedy strikes when people don’t consider the consequences of their actions is the famous story of Kamtza and Bar Kamtza, the archetypal tale in the Jewish sources of baseless hatred that leads to ruin.

The story of a powerful man

The story tells the tale of a powerful man in Jerusalem who had one friend named Kamtza and an enemy – though no reason for the animosity is given – named Bar Kamtza.

One day, the powerful man wanted to throw a banquet and sent a messenger to invite his friend, Kamtza, to the party. The messenger got confused and, instead of inviting Kamtza, invited the enemy, Bar Kamtza.

Party night arrived, and the host was aghast to see his sworn enemy sitting at his table, drinking his wine and eating his food, and demanded that he leave. Bar Kamtza urged the host to let him stay, first saying he would pay for his food and drink, then that he would pay for half the banquet, and when the host refused both those offers, he upped the ante and said he would pay for the entire feast.

The host still refused, took him by the hand, and threw him out. Those at the banquet, including the rabbis, said nothing. Humiliated and furious, eager to get revenge on the host and the rabbis who did not protest, Bar Kamtza cooked up a story that the Jews were planning a revolt and took it to the Romans. Ultimately, the Romans bought the story and set siege on Jerusalem.

The Kamtza-Bar Kamtza story is one of ego, wounded pride, and unwillingness to compromise – echoing the dynamics of the current political battle over the judicial overhaul plan. The rich host is unwilling to give in to Bar Kamtza, and Bar Kamtza – wanting to show that he is nobody’s sucker – pledged to take revenge. Neither man was willing to meet the other in the middle to avoid a disastrous conflict.

In the current political battle, there is also no small amount of ego, wounded pride, and an unwillingness to compromise: each side wants to show the other that they are not going to step down.

The government is plowing ahead with the change in the reasonableness clause partly because it does not want to look as if it is giving in to the protesters, and the protesters are continuing with their disruptions – even though this piece of legislation does not mean the end of democracy – partly because it does not want to give in to the government. Each side wants to show the other who is boss, and in the meantime, the country simmers, and its enemies rejoice as the country weakens from within.

Then there is the story of the zealots told on this daf. There were three wealthy men in Jerusalem who, between them, had enough supplies – wheat, barley, wine, salt, oil, and wood for fuel – to sustain Jerusalem for 21 years when it was under Roman siege. The rabbis wanted to try to make peace with the Romans, while the zealots wanted to fight. To compel the citizenry to fight, the zealots – completely sure of the righteousness of their path – set fire to the storehouses, triggering a famine that then paved the way for the Romans to destroy the city.

This is the Talmud’s paradigmatic story of the dangers of zealotry, of the perils of complete certitude, of being so sure of a cause as to be willing to take actions that harm the collective interest just to get the collective to follow a particular course of action.

The afflictions of Bar Kamtza and the zealots plague both the government and the opposition and protest movement.

Both the government and the opposition and protest leaders need to step down from their entrenched positions and recognize the harm they are causing the country. The way the judicial reform is being executed damages the country’s economy and hurts its international reputation, while the protests chip at the country’s solidarity and therefore compromises its national security. Both sides need to open up Tuesday’s Daf - Gittin 56 – and learn the lessons, and both sides need to do so immediately.