Goodness and Mercy Shall Follow Me: A Memoir of Old Jerusalem, the long-awaited English version of Avraham Frank’s 2007 Hebrew book, translated by his great niece, Nehama Stampfer Glogower, also the great-granddaughter of the legendary Rabbi Tzvi Pesach Frank.

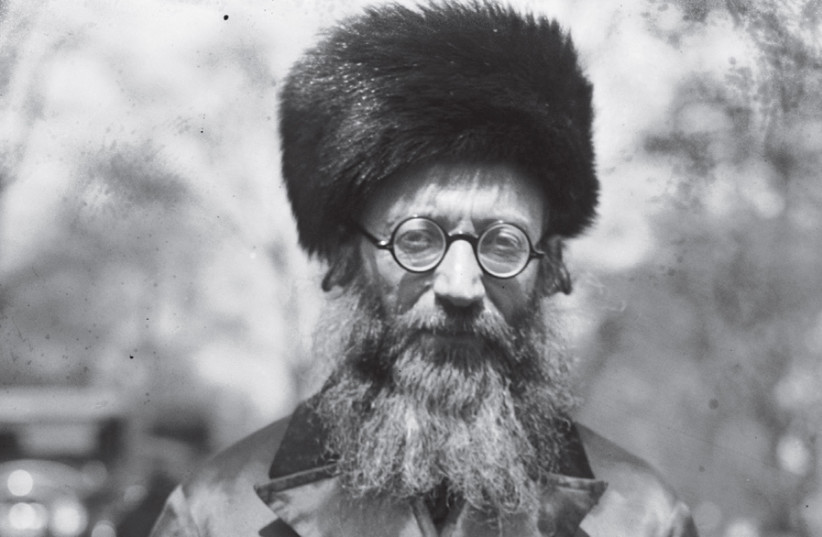

Rabbi Frank (1873-1960), who served as chief rabbi of Jerusalem in pre-state Palestine from 1935 until his death, was that rare combination of a leading Torah scholar and strong supporter of the Zionist movement. Educated in Europe in leading yeshivot, Rabbi Frank continued his studies after moving to Palestine at the age of 20.

He became very friendly with two other famous Zionist rabbis: his brother-in-law, Rabbi Aryeh Levin (1885-1969), known as the “Father of the Prisoners” because of his frequent visits to imprisoned members of the Jewish underground; and leading Zionist thinker Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook (1865-1935), the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel.

A trove of Jewish law writings left behind

Rabbi Frank left behind a trove of writings on Jewish Law. He was known for a sense of compassion that sometimes led to leniencies in his rulings, which lesser Torah scholars might not have permitted.

Israeli Supreme Court justice Haim Cohen (1911-2002), who had received an advanced religious education but later became avowedly secular, wrote of Rabbi Frank:

“He was a purely righteous man in all the senses of those two words. He was more compassionate, merciful, patient, and kind than any other judge or dayan [religious court judge] that I have encountered in my entire professional life.”

In the ultra-Orthodox circles that Rabbi Frank also frequented, he was grudgingly respected for his erudition, even by those who found his values overly “modern.”

AVRAHAM FRANK (1917-2013), his son, did not go into the rabbinate as most male members of his family. He fought in the Hagana and later in the IDF. He became the successful owner of a company called Techno-Kefitz (Techno-Spring), which manufactured springs used for peacetime purposes, but also for weapons used by the Hagana and later by the IDF.

Frank was also a gifted storyteller.

He learned some of his stories from his parents, including many about life in Jerusalem under the Turks before he was born. But most of his stories are from the time of the British Mandate. He writes about religious life in Jerusalem and about his involvement in the Hagana while maintaining good personal relationships with the other two main underground organizations, Etzel and Lechi.

The book also contains several short tributes to Frank himself, written by family members (such as Prof. Shaul Stampfer of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem) and other well-known Israelis (among them former Supreme Court justice Elyakim Rubenstein), and many photographs of old Jerusalem.

Stampfer Glogower has translated the book into very readable English that preserves the informal but engaging style of the original. She has added copious notes, both to help readers who lack a strong basis in Jewish religious practice and to provide detailed historical background for events that Frank alludes to. At times, she even points out minor historical inaccuracies in his narrative.

Most illuminating are the stories about the interplay before 1948 between the Jewish underground and the religious world. Frank himself played a significant role in this, as did his parents. Their home was used by the Hagana for hiding weapons – and they were not the only ones.

Whenever we read about the past, we see how both negative and positive themes repeat themselves in our time. For example, in this book we see that religious-political machinations in Israel are nothing new.

A little more than 100 years ago, Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook (Rav Kook) was approached by Agudat Yisrael and offered an appointment to its beit din (religious court). Rav Kook, whose name was already being submitted for important rabbinical positions, tempted by the offer, consulted his friend Rabbi Tzvi Pesach Frank.

Rabbi Frank understood that the motivation behind the offer was not pure. He explained to Rav Kook that this position would effectively make him ineligible for other rabbinic positions.

Beyond that, Rabbi Frank reminded Rav Kook that on a rabbinical panel of three judges, the two less liberal rabbis could simply outvote him on any significant issue.

As in these days, memoirist Frank reported how his unit of 10 men in the Hagana was made up of people who “came from different traditions and had different points of view, but this did not get in the way of creating long-lasting friendships. There was fellowship between the religious and the secular, and mutual respect.”

Since the fighting against external enemies ended, however, “Both sides have become more extreme, and I blame parties on both sides of the divide,” he said.

Avraham Frank’s timely message, now available in translation, is that “A nation without faith can’t endure, and faith without a nation is a return to exile. These mutual needs were well understood by the Jews of Eretz Yisrael in that era, before we had a state of our own.”

- GOODNESS AND MERCY SHALL FOLLOW ME: A MEMOIR OF OLD JERUSALEM

- By Avraham Frank, translated by Nehama Stampfer Glogower

- Luminaire Press

- 243 pages; $13