For hundreds of years my family, the Tichos, lived, thrived and persevered in the small Moravian town of Boskovice. And then, in one dreadful blow, they were all gone. Today there isn’t a single Jew in the town.

It is in this spirit that I’ve undertaken other projects, such as restoring of the house in Boskovice where my grandfather Yitzhak Zvi Ticho, was born, placing a plaque on the birthplace of Anna Ticho, restoring the graves of our grandparents in Boskovice and Berlin, placing a plaque to remember the Jews who were locked up in the Spielberg fortress, participating in the restoration of the synagogue in Boskovice, and undertaking the tracing of our family tree as far as we could manage.

It was also in this spirit that I led a delegation of family members in 1998 to the Czech Republic, where we visited the many sites connected with the history of the family. Four years later I brought our daughter Robin, her son Michael and our son Richard for a similar visit in order to make them aware of the roots of the family. And then, in 2004, I returned to the family sites with my son Ron, his wife, Pam, and their three children, Nathan, Hannah and Connie.

A key element of this last tour in 2004 was a gathering of our family, along with the ambassador of Israel and some 20 members of the press, on Brno’s Spielberg fortress to dedicate a memorial plaque that we sponsored to the Jews who were imprisoned there by the Nazis during World War II. And it was also in this spirit that we undertook to make a special presentation during Nathan’s wonderful bar mitzvah celebration in December 2004.

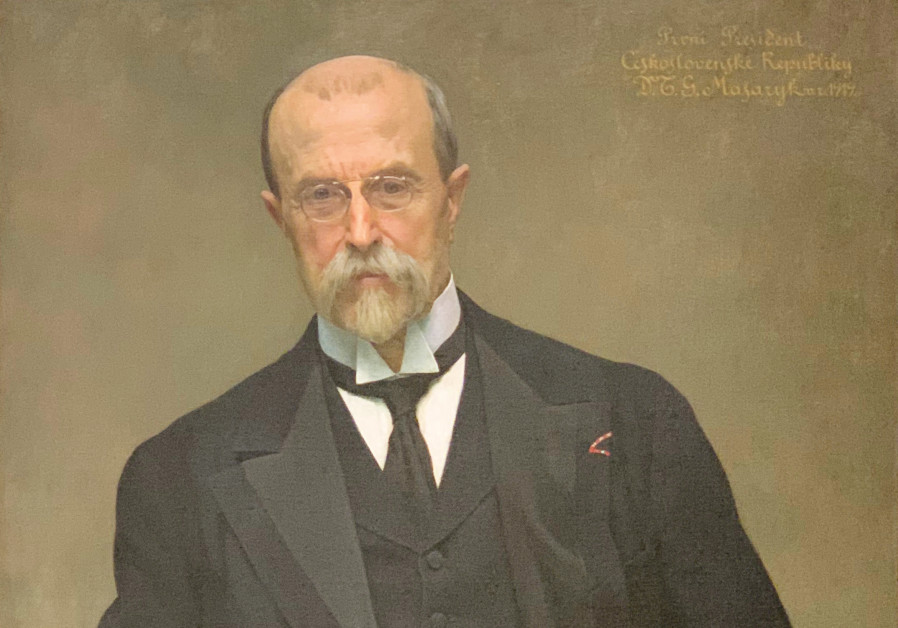

After the First World War, in 1918, Bohemia, Moravia, Slovakia and Subcarpathian Russia were combined to form Czechoslovakia. Under the benevolent and liberal administration of the founder and first president, Thomas Garigue Masaryk, this mixture of Czechs, Germans, Hungarians, Gypsies, Poles, Russians and Jews thrived and lived in comparative harmony. Today, Ukraine has absorbed Subcarpathian Russia, and the Slovaks have decided to go their own way. Typical of the non-confrontational nature of the Czechs, the parties split amicably, and Bohemia and Moravia now form what is today’s Czech Republic

One could easily assume that the ethnic Czechs living in Moravia, surrounded as they were for the past millennium by militant countries such as Germany, Austria, Hungary, Poland and Russia, might have been the victims of constant turmoil. Actually, the opposite was true. Moravia – located off the path of the Crusaders, away from the conflict between the Catholic Church and Protestant firebrands, and of relatively modest economic and political importance – was usually bypassed and ignored as power struggles made the rest of Central Europe a focus of many conflicts.

So it shouldn’t be a great surprise that even today, most of the visitors to Boskovice are not foreign citizens but rather Czech nationals. They climb the lovely wooded mountain to visit the fortress that once dominated the valley below, walk the streets that once were the Jewish ghetto, or tour the castle at the bottom of the hill that was and still is the seat of the Mansdorf-Pouilly family, the aristocrats placed there by the Austro-Hungarian Empire centuries ago to keep the Czechs under control and to “protect” the Jews.

IT WAS this unique position of Moravia, away from the turmoil and turbulence that affected the rest of Europe, that created an unusual and fertile atmosphere for the Jews living in this region. While the kings in Prague and the emperors in Vienna formulated rules and edicts governing the lives of Jews, in Moravia these laws and regulations were often ignored or not enforced. As a result, Jewish life, with few exceptions, tended to be civilized and humane.

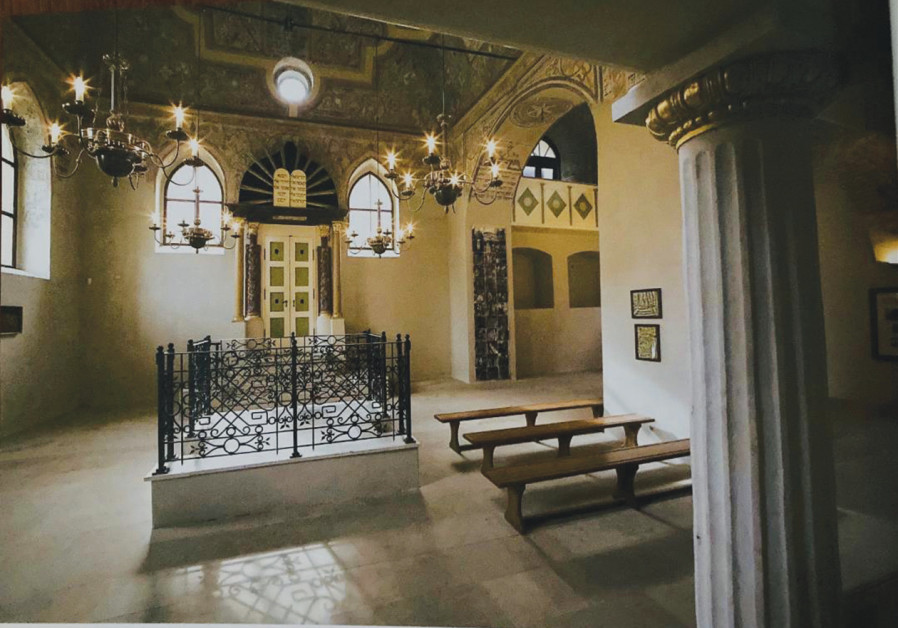

Visitors to Boskovice, as a result, can wander a few yards from the castle and visit the well-preserved section of the town that once constituted the Jewish ghetto. They can walk the few narrow streets, look for signs of the Jewish life that once thrived here and, perhaps, visit the 330-year-old synagogue, one of the most unique houses of worship in the world. Now fully restored, this temple is decorated throughout with attractive and beautiful murals and religious writings.

This synagogue was already 100 years old, when a local scribe sat down and carefully and painstakingly started to create a perfect copy of our sacred Scripture, the Torah. By the time my grandfather was born in 1846, this Torah had already served three generations of Jews as they gathered each day and on Shabbat to practice the faith taught to them by their previous generations. In 1899, when the Torah had already reached the age of 110, it may have served during the bar mitzvah of my father, Nathan Ticho. And when the First World War started in 1914, the venerable Torah scroll continued to mark the passing of each year as it provided the sacred readings each time the congregation met to pray.

Then, on March 15, 1939, the Nazis marched into the country and soon many things changed. The synagogue of Boskovice was ordered closed and all of the congregation’s possessions, including all its Torah scrolls, were shipped to Prague so that one day the Nazis could create a “Museum of an Extinct Race.” On March 19, 1942, all the Jews of Boskovice, including several members of the Ticho family, were rounded up and sent to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. From there, these 400-plus Jews from Boskovice were sent to death camps in the East from which only 14 returned. Today, after a millennium of Jewish life in Boskovice, there are no more Jews. The only things that remain are the synagogue, the cemetery, the ghetto streets and houses and the sacred articles collected by the Nazis that are now stored and cared for in Prague by the Jewish Museum.

This sacred and honored survivor of the Holocaust, now resides in the warm and friendly surroundings of Congregation Brith Sholom in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, passing on its power and inspiration from one generation to the next.

It is in this m’dor l’dor spirit that I have endeavored to pass on this story of our family and to the future.