En route to Alon, the handsome new buildings of Anata, an Arab village whose recent construction is a sign of new-found prosperity. Further east a few kilometers, hills of green, the giant footsteps of the Jewish madness for that exhausted cliché: making the desert bloom. Hundreds of apartment houses and smaller dwellings cross the horizon at Maale Adumim.

Alon sits aloft the ridge, with stone-clad houses built in orderly rows. Below them, the bar mitzvah service is held in a saucer-shaped valley, sunny and verdant. Near the entry path, two tables are set up, covered respectfully with the velvet synagogue coverlets, and on one lies a white round special case enclosing the scrolls of the Torah. At one end, there is a playground with a slide, a sandbox and a few spinning play platforms and swings. In between the playground and entrance is a grassy area. There are chairs spread on three sides of the tables and straggling in an uneven line further off where the women sit, in proximity, yet far enough away for the orthodox to feel it is sufficient.

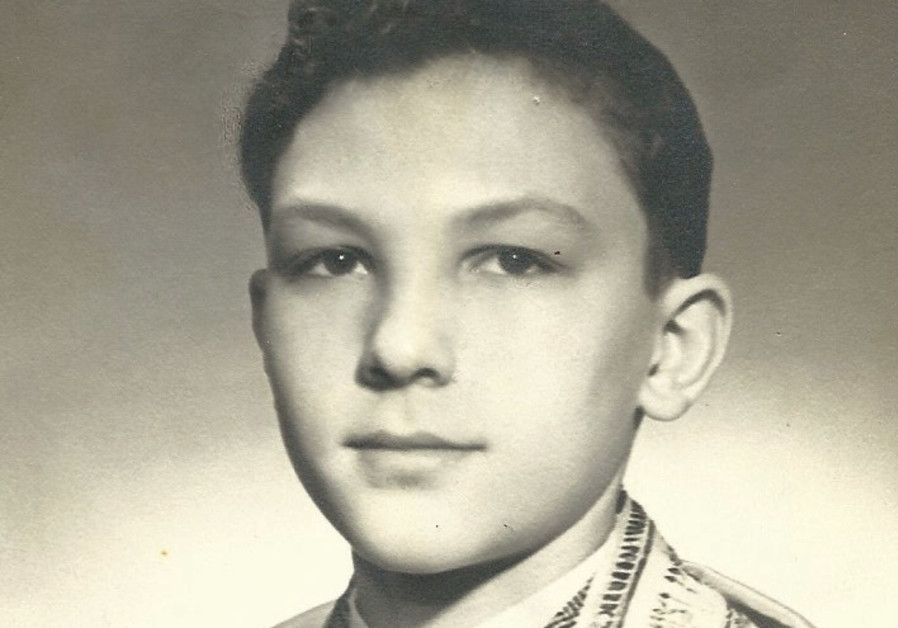

I flashback to my bar mitzvah, on a cold January day in Toronto.

The entire family was dressed in new clothes. My father’s and my suits were hand-tailored, mine a light gray-green three-piece tweed. He was wearing a pearl-gray fedora. I wore a smaller one of course but do not recall its color. We had a one-hour walk ahead of us, over two miles along windy streets.

Fortunately it was not snowing, nor had it snowed in the past few days. Still it was cold. My father pushed a high-sprung baby carriage, in it my baby sister, Simmy, three years old, bundled up carefully against the chill. Tucked in along the sides of the carriage, were three or four bottles of Canadian whiskey, covered by blankets against prying eyes, assiduously saved from the monthly ration imposed in that wartime year, 1944.

The bar mitzvah takes place in the Talmud Torah Etz Chaim. The two-story building included classrooms for the afternoon school, and behind them was the spacious synagogue, capable of seating a few hundred men and above, on three sides, a women’s gallery.

My father and all the adult men, the older usually bearded, prayed aloud in their Polish Ashkenazi Hebrew. The Torah reader as well seemed to roar out the Hebrew in that accent and in a voice that originated in his lower abdomen and passed through his nasal passages before abusing our ears.

Uncles and my father were honored by being called to the Torah in their turn, and finally it was time for me to recite the blessings, the concluding section of the Torah reading, and the haftarah, the lesson from the Prophets.

My older sisters, ages 17 and 18, clad in newly bought dresses, had been downstairs in the large event-cum-dining hall helping the cook prepare the food which had been kept warm since Friday evening. My sister Pearl almost cried when she realized that they had missed my reading. Their help cut service costs; anyway my father must have borrowed money to put on such a lavish lunch for our large extended family and a handful of friends. But I was an only son.

There was a stage in the corner of the hall, and at the chosen moment, I stepped up on it, and made my bar mitzvah speech – in Yiddish. Of it I have neither a copy nor recollection, but for the usual warm thanks to my parents and my teacher, Mr. Abella.

I had my first out-of-body experience then. It was as though I was up above myself, looking down at the boy on a platform. He stood relaxed, his left hand in the pocket of his tweed suit jacket, and delivered his first public address.

Back to Alon. Ayal read the entire Torah portion, 111 verses, and a long lesson from Isaiah 43:21-44:23. I had begun teaching him the blessings and haftarah, as I had his mother, decades earlier. Due to scheduling difficulties, his grandfather, Daniel Avihai-Kremer had to take over. How different studying in Hebrew with a bright Israeli child, who has had a (liberal) orthodox schooling and homelife.

How deep the sense of continuity when I blessed him in the millennial “May the Lord bless you and keep you,” my hands on both sides of his head., just as I had when he was two days old.

The dozens of children were summoned from the playground in time to toss candies at the newly responsible young Jew. Ayal had written his “speech” or rather, dvar Torah in great part by himself, helped by his father. Except for me, who wore a blue jacket, all the men and boys wore their white shirts over their trousers; some women were in slacks, some had their heads covered.

All was simple, ceremonial but informal, natural and not ripped out of the general context of life, as mine was in Canada, and my father’s in a small Polish shtetl.

Even the kiddush on the playground was quintessentially Jerusalemite, kugel, herring, wine, and a friend walking around puring small jiggers of whiskey. My granddaughter, Halel Sarah Rubin, spoke, carrying on a rhetorical talent inherited from my mother whose name she bears.

The day this issue goes to press our oldest granddaughter, Carmel Levinson celebrates, a year later due to Corona, her bat mitzvah. She too will read the Torah and will teach a Dvar Torah following the example of her egalitarian orthodox mother, Sharon Mayevsky.

The haftarah from Isaiah contains the beautiful passage “Fear not, My servant Jacob.” It promises continuity, return to independence and banishment of fear.

Here we are. A link in an unbroken chain. Though many links were shattered and smashed, and fear was a constant, now we stood at Alon, named after a young Jewish general separated from the previous Jewish generals by almost two millennia.

To them I say, I am happy to be Jewish. I delight in being part of the chain. I knew my grandfather, know my great grandchildren and am the link which made the leap from exile in Poland, from the Diaspora in a good and great land, Canada, to my dream and Isaiah’s promise.

Now we have four generations here. As I write this, during Pesach, the festival of matzot and freedom, the holiday joy is doubled.

Oh yes, the howling wilderness. On our return drive the wind did howl But sometimes it howled doubly, especially when we drove around a curve in the road. That’s when I guessed – correctly – that a piece of the car’s fender lining had come loose and was riding the tire, which howled in protest.

Even in this there is a lesson. Though we live in history, it is made up of the ordinary things of life as well. Love of family must be both.