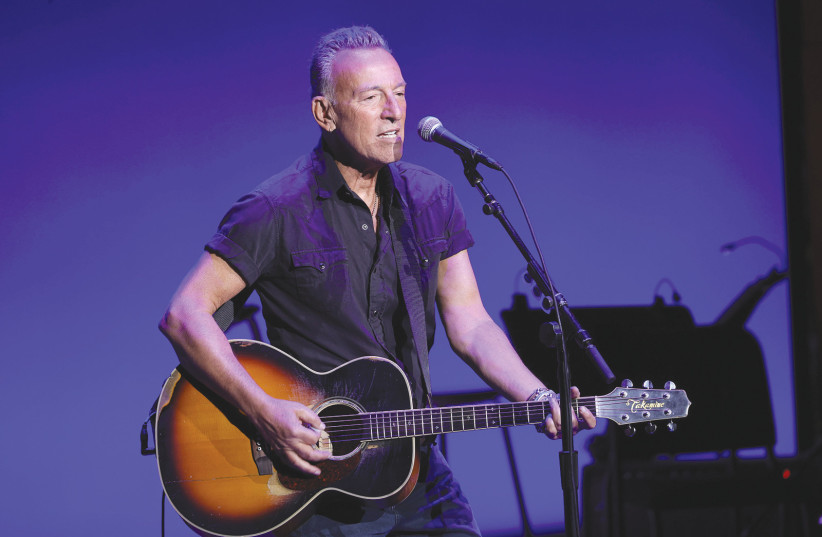

Bruce Springsteen’s iconic song, “Adam Raised a Cain,” is an autobiographical account of his tortured relationship with his father. He reflects upon what he has referred to as “the hard inheritance handed down from father to son” (Bruce Springsteen, Born To Run, p. 265):

In the Bible Cain slew Abel

And east of Eden he was cast;

You’re born into this life paying

For the sins of somebody else’s past.

Springsteen’s reading of Cain and Abel reflects a dark view of life: since the time of Adam, Eve and their murder-cursed sons, Cain and Abel, we’ve wanted to believe we are free to become ourselves, but we are hemmed in hopelessly by our worst family histories from the moment we leave the womb. This is a powerful interpretation of the Cain and Abel story, which Jews worldwide read yesterday on Shabbat.

The differences between the book of Genesis and Springsteen's song

However, from a Jewish perspective, it is quite inadequate. When read closely and in the larger context of the entire book of Genesis, this mythic story of the world’s first murder reveals a no less difficult, yet more redemptive, message about our nuclear, extended, national and global human families.

Cain’s murder of his brother Abel is a symbol of the violent and destructive tendencies of human beings toward each other. Critical to the story seems to be Cain’s depressive rage born of jealousy that God has, without any reason, favored Abel’s offering over his own.

Were this merely a story about the inevitability of sibling rivalry, jealousy and violence, it would have told us about these things only, with no subsequent expression of tragedy and moral outrage. However, packed into the brief and sparse Cain and Abel narrative (Genesis 4:1-16) is an abundance of morally significant exchanges between Cain and God, the frustrated “Parent-Creator,” who warns Cain that:

Sin crouches at the door.

Its urge is toward you

But you can rule over it. (Genesis 4:8)

Further, the story repeats in varying grammatical forms the Hebrew word, ach, brother, six times, (Genesis 4:2, 8, 9, 10.) This emphasizes the Bible’s insistent message that – paraphrasing Cain’s cynical rhetorical question in verse 9 – we are indeed our brother’s keepers. Cain is punished by God for his fratricidal crime with nomadic exile (Genesis 4:11-16).

Together with God’s admonition about fraternal responsibility, this should be sufficient to prevent humanity from repeating Cain’s evildoing; however, no more than 10 generations after Cain, Noah builds his ark to save a tiny remnant of living things from the devastating flood that God inflicts upon humans and animals, “For the earth is filled with lawlessness because of them: I am about to destroy them with the earth” (Genesis 6:13).

Upon first reading, we might assume that Springsteen was correct: our persistent refusal to be our brothers’ keepers proves that we are born into this life paying for the brutal sins of our (ancient) ancestors’ past.

The rest of the book of Genesis proves this assumption wrong, howbeit very gradually, demanding tremendous patience and faith from its readers. The (in)famous biblical narratives that follow, concerning vicious sibling rivalry and domestic discord in Abraham’s extended family, seem at first glance to present a textbook case of stubborn multigenerational dysfunction.

Abraham’s wife, Sarah forces him to choose between their son, Isaac, and Ishmael, his son with his second wife, Hagar, both of whom Abraham banishes to the desert (Genesis 20). Isaac and his favored son, Esau, are deceived into handing over Esau’s birthright and paternal blessing to his younger brother, Jacob. Jacob colludes in the deception with their mother, Isaac’s wife Rebecca, who favors Jacob (Genesis 25-27).

Esau’s rage at his brother leads him to vow, “I will kill my brother Jacob” (Genesis 27:41). After years of being paid back in kind by God and family members for his deceptions, Jacob suffers the ultimate deception when his 10 older sons kidnap and sell their younger brother Joseph into slavery out of jealous rage at his status as Jacob’s favored child, then tell their father that Joseph has been killed.

Each of these stories echoes to an extent Cain and Abel’s fatal interaction, coming dangerously close to repeating that first fratricide. Beginning with Eve (Genesis 4:1-2), then God, (a parental “stand in,” as it were, in Genesis 4:4-5) each generation in the family of Abraham has a story about parental favoritism, sibling jealousy, competition and rivalry.

In almost every story, the life of the younger sibling is put at serious risk. (The exception is Ishmael the older brother, but Isaac nonetheless later survives the ordeal of nearly being sacrificed by his father.) However, the echo ends there, for in each story the tragedy of Cain and Abel is subverted, transformed and redeemed.

Not only do the younger siblings not die, but they also successfully push back on the rigid social mores of primogeniture (older sibling advantage), to their own hard-earned benefit. Isaac becomes the bridge to Jacob, who becomes the formal founder of the Israelites, while Joseph becomes Egypt’s second-in-command.

Yet the sweep of family redemption is even wider and more generous than this. The older siblings, stymied at first, also receive blessings in the end. Ishmael, Esau and Joseph’s brothers become founders of three great nations of the ancient world: the Ishmaelites, the Edomites, and the Israelites.

Then, this subversive and redemptive arc extending from Cain and Abel goes even further. Esau and Jacob reconcile after years of estrangement (Genesis 33), Ishmael and Isaac reunite to bury Abraham (Genesis 25:9), while Esau and Jacob reunite to bury Isaac (Genesis 35:29).

The most masterful of all these subversive narratives – the one that brings Cain and Abel to its most redemptive resolution – is the Joseph narrative (Genesis 37-50). A work of consummate literary artistry, this extended story takes Joseph and his brothers from sibling rivalry, rage and betrayal all the way to regret, repentance, reconciliation and tearful reunion.

It is Judah, leader of the brothers and instigator of Joseph’s kidnapping, who finally undoes the “curse of Cain” when he takes full responsibility for the welfare of their youngest brother, Benjamin, (also Jacob’s favorite), defending his life and liberty before Egypt’s second-in-command. We are treated to the delicious irony that this powerful leader is none other than Joseph in disguise.

Judah responds tellingly to Cain’s cynical question, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” when he begs Joseph, the one he had betrayed years before, “Please let your servant remain as a slave to my lord instead of the boy and let the boy go back with his brothers” (Genesis 44:33).

The brief but beautiful coda to all these tales is that of Ephraim and Menashe, Joseph’s sons. Their blessings from grandfather Jacob replay the same pattern of favoring the younger over the older sibling, yet this never leads them to the rivalries of their ancestors (Genesis 48).

With tortuous, loving gradualness, the generations of the family of Abraham bind up and heal the infected laceration of the first family’s murderous, abusive hatred. None of their stories justify or dismiss the lasting horror of familial abuse and violence; nor do they assume that we will always be fraternal and never fratricidal within our many concentric circles of family.

What they do is allow us and our many different types of siblings – nuclear, extended and global – to envision the great possibility that where hatred exists, so too do forgiveness, love and responsibility. These majestic tales of Genesis reassure and admonish us that the answer to Cain’s question, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” is this alone:

Yes, we most certainly are.

The writer is the rabbi of Congregation Ohav Shalom, living with his family in Albany, New York, where he also teaches Judaic Studies in the middle school of the Hebrew Academy of The Capital District.