I spent the last days of 2022 on vacation in Jordan. Although I had been to the Hashemite Kingdom several times for work, this was my first visit as a tourist. Entering Jordan at the Yitzhak Rabin Crossing, some three km. from Eilat, I traveled to Petra to see the renowned tombs and temples carved out of the pink sandstone cliffs.

Before the 1994 Israel-Jordan peace treaty, such visits were impossible for Israeli passport holders, though some chose to visit illicitly. Throughout the 1950s, reaching Petra held a magical allure for young Israelis – a popular song celebrating “the red rock” inspiring the precarious journey.

All in all, very few Israelis reached Petra and returned home to tell the story, among them famed paratrooper Meir Har-Zion. A dozen Israelis apparently lost their lives in the effort, killed by the Jordanian military after illegally crossing the frontier.

That pre-peace period saw recurrent eruptions of Israel-Jordan bloodshed, but relations between the Jewish state and its eastern neighbor were always more intimate than they were with other Arab countries.

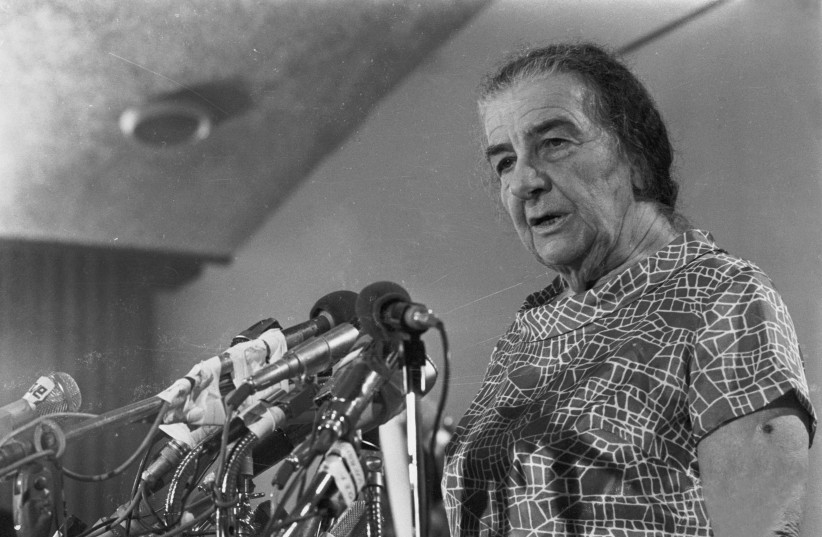

Golda Meir, then acting head of the Jewish Agency’s Political Department, met twice secretly with Emir Abdullah of Transjordan in the lead-up to Israel’s independence (Jordan was called Transjordan until it took control over areas west of the Jordan River in 1948).

Meir’s mission was to find a modus vivendi with the emir that would avert full-scale war. Both Zionists and Hashemites viewed Palestinian leader Amin Husseini as an enemy, and on that basis, it was believed understandings could be reached.

However, in May 1948, when all the neighboring Arab countries attacked the newborn Jewish state, Transjordan was among them. Its army, the British-commanded Arab Legion, was the most formidable of the Arab fighting forces, and the 1949 armistice agreement left Amman in control of east Jerusalem and the West Bank.

Not peace but collaboration

MUCH HAS been written about Zionist-Hashemite collaboration. Israel undoubtedly preferred Jordanian control over the West Bank to that of Amin Husseini, and, following the armistice, there were preliminary conversations about a full peace. But on July 20, 1951, when King Abdullah was murdered at Jerusalem’s al-Aqsa Mosque by a Palestinian nationalist, any such hopes evaporated.

Abdullah’s grandson Hussein, who personally witnessed the assassination, was to sit on the Jordanian throne from 1952 until his death in 1999. For the lion’s share of his half-century reign, Jordan never made peace with Israel. Nonetheless, King Hussein cultivated avenues of communication and cooperation with Israel, repeatedly conducting surreptitious meetings with Israeli leaders.

In the lead-up to the 1967 Six Day War, Israel sent messages to Hussein urging him to stay out of the conflict, but the Jordanian monarch – wishing to avoid breaking with Arab solidarity – chose to join the fray. That much-criticized decision cost Hussein the western part of his kingdom, but it is argued that had he remained aloof, the hostile Arab reaction might have cost him much more.

Hussein faced a serious threat to his reign in September 1970 when the Syrians invaded Jordan in support of the Palestinian fedayeen, who were in open revolt against the Hashemite throne.

Cold War realities dictated that Washington be concerned about the collapse of a pro-Western regime and its replacement by one in the Soviet orbit. But America was overstretched due to the Vietnam War and coordinated with Israel to fill the power vacuum: the IDF mobilizing in northern Israel, forcing the Syrians to withdraw and allowing Hussein to crush the Palestinian insurgents. The Hashemite Kingdom was thus saved, and the US-Israel strategic partnership was born.

The cold peace

JORDAN’S NUANCED approach toward Israel was manifested in the October 1973 Yom Kippur War. On one hand, Hussein quietly warned prime minister Meir of the imminent Egypt-Syria surprise attack, and following the outbreak of hostilities, kept the Israel-Jordan frontier quiet. On the other hand, so as not to be seen as abandoning his Arab brothers, the king dispatched an armored brigade to fight the IDF in Syria.

Despite Hussein’s much-cultivated image as the Arab world’s foremost moderate leader, he refused to support Anwar Sadat’s 1977 peace initiative, never closing the door to peace, but neither embracing it.

This changed with the 1993 Israel-Palestinian Oslo Accords, which gave the king the pretext to normalize ties; Hussein and Rabin signed the Israel-Jordan Wadi Araba peace treaty the following year.

Hussein’s personal commitment to a reconciliation was demonstrated in March 1997 after the murder of seven Beit Shemesh schoolgirls by a Jordanian soldier at Naharayim on the Israel-Jordan border.

The king paid condolence visits to each of the bereaved families – his behavior touching the hearts of Israelis, while antagonizing many of his own countrymen (those opposing normalization criticized him for “kneeling before the Jews”).

But despite the early optimism, Israel-Jordan relations deteriorated into a cold peace. Jordanians accused Israel of not fulfilling promises for cooperation and for never sufficiently considering Jordanian sensitivities.

Particularly irking for Jordan was the Mossad’s 1997 botched assassination of Hamas leader Khaled Mashaal in Amman, and Jerusalem’s 2017 celebration of the Israeli security guard who shot dead two Jordanians during a terror attack at an embassy residence.

For some Jordanians, fears persist that Israel continues to see Jordan as the alternative Palestinian homeland – ideas that had been expressed by the younger Ariel Sharon (who later gained much respect in Amman for his championing of Israel-Jordan ties).

Israel's new partners

JERUSALEM, TOO, has its grievances. Whatever Israel did – whether providing water above and beyond the commitment made in the peace treaty, or supplying low-cost Mediterranean gas – such support was never adequately acknowledged in Amman.

Israel was also disappointed when Jordan refused to use its professed moderating influence to help diffuse potentially dangerous situations, especially when events on the Temple Mount seemed to be escalating.

The 2020 Abraham Accords with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain left Jordan feeling sidelined, with Israel supposedly embracing new peace partners at the expense of its older one.

In July 2021, prime minister Naftali Bennett reportedly met with Jordan’s King Abdullah in secret, raising questions as to why, despite the formally normalized relations, Amman still insists on a clandestine meeting.

This week, when Middle East peace partners Bahrain, Egypt, Israel, Morocco and the UAE met in Abu Dhabi for a Negev Forum meeting, Jordan was once again absent.

For domestic reasons, Amman remains acutely responsive to Palestinian sentiment. Given that an Israeli-Palestinian breakthrough is unlikely to happen anytime soon, Israel-Jordan ties will be condemned to the back burner.

The writer, formerly an adviser to the prime minister, is chair of the Abba Eban Institute for Diplomacy at Reichman University. Connect with him on LinkedIn, @Ambassador Mark Regev.