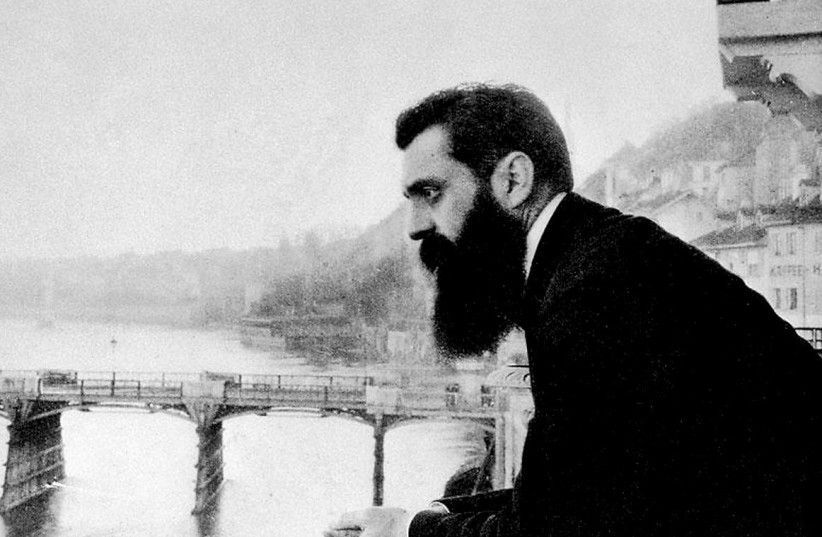

Who was that mystery man who shadowed Theodor Herzl as he walked through the Munich synagogue in the summer of 1895?

Herzl had a few mystery figures accompanying his journey. Were they real? Augmented? An allegorical figuration of his abstract ideas?

Herzl chose Vienna’s chief rabbi, Moritz Gudemann, to be the second person to share the full intricacies of his revolutionary vision. The first one warned Herzl that the rabbi would think he had gone completely mad.

Herzl convinced Rabbi Gudemann to travel all the way to Munich that weekend without sharing many details in advance. That Saturday morning, the rabbi walked into the Munich synagogue, where the Torah reading was from Parashat Re’eh: “I set before you this day a blessing and a curse.” As Moses is about to depart, he tells the nation of Israel that they have “tough choices” to make. In what remains an anchor of the Jewish faith until today, Moses instructs the Israelites to choose the blessing over the curse, to choose life.

Herzl arrived in Munich that morning by train from the southern Austrian lakes. Sometime after the Shabbat service concluded, Herzl walked into the synagogue.

“In the late morning hours, I did not yet mention the matter,” Herzl recounted about his meeting with the rabbi. “For the most part, I let Gudemann do the talking, and he has yet to dream in his soul that later that same day, he will call me Moses!”

As the two walked around the synagogue, they were not alone. Herzl wrote that they were shadowed by a man who to Herzl resembled no other than Otto von Bismarck – the father of united Germany and of German nationalism.

Unlike others, Herzl understood that Jews are defined by European opposition to them, and that just like in the case of Moses, they are not equipped to listen to his vision due to “shortness of spirit and hard labor,” or in Herzl’s words, “When we left the ghetto, we were and remained the same ghetto Jews.”

The way to transform the Jews is through the outside. Just as the outside held the keys to the transformation of Jews in Moses’ time (see box), so was the case in Herzl’s time. That outside had the figuration of this thin tall man walking behind Herzl and the rabbi around the synagogue. “It was a strange atmosphere to have a Bismarck figure walking behind us with the key chain in his hand, while the rabbi was showing me through the temple,” Herzl wrote. “The goy did not know that he looked like Bismarck; the rabbi had no idea that he was doing something symbolic in showing me the beauty of a temple. I alone was aware of these as well as other things.”

That evening, Herzl presented the depth and complexity of what was to become the vehicle to transform the Jewish nation: Zionism (Judaism 3.0). Upon comprehending Herzl’s vision, Rabbi Gudemann proclaimed to Herzl: “You are in my eyes like Moses.” Later that night, as the rabbi walked Herzl to the train that would take him back to the Austrian lakes, he urged Herzl, “Keep doing as you do. It is possible that you are the messenger of God.”

129 years later in Munich (2024)

Two years after that pivotal Shabbat, Herzl was ready to gather the Jews in Munich for the first Zionist Congress, but the “opposition Jews” of Munich, still “ghetto Jews,” as Herzl called them, forced him to relocate to Basel, Switzerland.

Some 40 years later, a different type of opposition emerged. Antisemitic biles were heard in Munich and throughout Europe: The Jews in Europe dehumanize Europeans, they extract too much power, they pollute the wells. Those biles led to tragic consequences.

And then came 2024, another Shabbat in Munich, another arrival; and again, the Jewish nation was asked to make a “tough choice.”

Three times in recent years, the Jewish nation was asked to make a similar choice, but unlike in Moses’ time it was not clear which path leads to a blessing and which to a curse.

In 1993, the nation chose to enter the Oslo Accords. We now know it led to an intifada that claimed the lives of more than a thousand Israelis, gave rise to the international “conflict industry,” and turned a defeated, bankrupt, and globally outcasted enemy into a well-armed, well-financed, and globally loved one.

In 2000, it chose to unilaterally withdraw from Lebanon. We now know it led to the Hezbollah takeover of southern Lebanon, the 2006 Lebanon War, and the 2023 Hezbollah-Israeli conflict, which displaced Israel’s northern residents.

In 2005, it chose to unilaterally withdraw from Gaza. We now know it led to the Hamas takeover of Gaza, 15 years of missiles and rockets fired into Israeli homes, and the Oct. 7 atrocities, which claimed the lives of 1,400 Israelis in one day and the displacement of Israel’s southern residents.

And now in 2024, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken at the Munich Security Conference asked the Jewish nation to once again make a “tough choice.”

However, this time it is crystal clear to Israelis which path leads to the blessing and which to the curse: The suggestion that Israelis should suicidally support a Palestinian state as the outcome of the Oct. 7 massacre is outright delusional.

This is especially true since the pressure and threat have been dramatically augmented. The same antisemitic biles heard in Europe in the 1930s – Jews dehumanize Europeans, Jews pollute the wells – are now being heard again: Jews in Israel dehumanize Palestinians, as Secretary Blinken suggested last week in Jerusalem, and then on that Shabbat in Munich as he answered a question about Israeli operations in Gaza, “The greatest poison in our common well is dehumanization.”

This underscores that the existential threat to Judaism has shifted. It is no longer eradication, one by one, of Jews poisoning the wells; it is eradication, collectively, of the Jewish state poisoning the common well of humanity through dehumanization.

So who was that mystery man who shadowed Herzl in Munich in 1895?

The answer might be found in Munich 2024. ■

A biblical mystery some 3,000 years earlier

When Moses led the Hebrews through the parting sea, a little-noticed biblical mystery occurred: The Egyptians finally recognize God. “Egypt said: ‘Let us flee from Israel; for the Lord fights for them against Egypt.’”

Yet such recognition seems to be in vain, since none of those Egyptians survived – not even one, as the Bible reiterates. From this we can ascertain that the recognition was not for the sake of Egypt but for the only people that were there to hear their recognition – the Israelites.

Indeed, shortly thereafter, earlier doubts among Israelites were gone: “and they believed in the Lord, and in His servant Moses.”

Forty years later, when presented with the choice, the nation of Israel chose the blessing and enjoyed a thousand years of flourishment (Judaism 1.0). However, toward the end of this era, when European powers invaded and aggressively tried to impose their values, frameworks, and paganic concepts, Israelis succumbed to the pressures and chose the curse. As warned by Moses, this choice had dire consequences: exile and re-enslavement in Europe (Judaism 2.0). Now a choice again.

The writer is author of Judaism 3.0: Judaism’s Transformation to Zionism (Judaism-Zionism.com). For his geopolitical article: EuropeAndJerusalem.com. For applying Herzl’s philosophy to today’s issues, see the Brazil Jewish Academy course: Applying Herzl (Judaism-Zionism.com/Herzl-course).