Four years ago, the world shifted. Beginning in March 2020, humanity suffered a worldwide pandemic which took close to seven million lives.

The COVID-19 outbreak upended our routines and disrupted our lives, professional careers, education, social interactions, and travel. We all assumed that this devastating pandemic would be the life-altering episode of our generation, the stories we would convey to incredulous grandchildren.

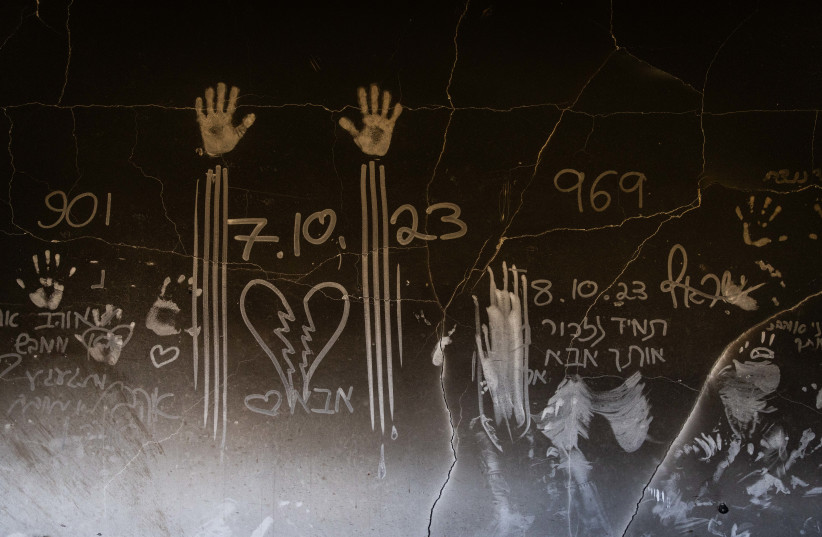

Little did we know that just over three years later an even greater earth-shattering event would rock the foundations of Jewish identity. The tragedy of Oct. 7 dwarfs the shock of the coronavirus. Now who even mentions the pandemic anymore? Oct. 7 and our responses to this massacre will shape our generation’s identity. Of course, only God knows what else is in store for us.

During a short four-year interval, we experienced two overwhelming upheavals, each of which inflicted tragic loss of life. Understandably, during the past few months we were more attuned to our own losses but, unfortunately, there is too much unnecessary death on both sides.

It is almost impossible to discriminate between innocent Gazan civilians and the overwhelming majority of Gazans who collaborated with Hamas. Our soldiers discovered Hamas paraphernalia and munitions in almost every civilian home. However, many innocent people have been caught in the crossfire of this just and moral war.

Such is the horrid legacy of terror. It kills indiscriminately.

Both of these cataclysms have left us with questions of faith. Why does God allow a pandemic to take innocent lives? How could He allow such widespread suffering? How could He have permitted Oct. 7 to unfold? Isn’t life in Israel meant to be different, immune to the suffering and persecution we endured in exile?

The world around us is swirling, and our minds are spinning.

Religious people respond to a crisis with faith, prayer, and good deeds. We respond to aggression and genocidal violence with greater unity of spirit and action. In the wake of these two overpowering moments, however, we must also adjust our religious voices.

These two mega-events taught us that we don’t have all the answers and that we must articulate our faith, religion, and hopes for Israel in a more unpretentious and humble voice.

Under a boulder

Moses thought that he completely understood God. He had a front-row seat to a series of 10 awe-inspiring miracles that liberated a nation of slaves. Moses had split the seas and ascended the heavens. After the terrible debacle of the golden calf, he fervently prayed for our forgiveness and rescued an entire people from possible extinction.

When Moses’ request for penitence was granted, it all seemed to make sense. During those heady months of revelation, Moses had discovered that God, the God of creation, was also the God of history, the God of law, and the God of mercy and compassion.

Having discovered these basic tenets of monotheism, Moses lodged an ambitious request of God: “Show me Your essence and teach me Your ways.” Moses wanted to study the deeper essence of God.

God’s response signaled to Moses that his request was impossible to grant. The human imagination cannot possibly comprehend the divine mystery. God is fundamentally different from human experience, and His wisdom and motives lie beyond human reach. As Moses sheltered under a large boulder, God passed before him and cautioned Moses that man can never “see” God, nor can he completely grasp Him. From his obscured view, Moses could only peek at God’s “back” and not His essence. He is only granted a fleeting glimpse of God.

Of course, as God doesn’t have a back, this phrase is merely a metaphor. The Hebrew word for “back” is achorai, which alludes to the conclusion of a process rather than its inception. By declaring that man can only glimpse His back, God assured Moses that ultimately, when history concludes, divine actions will make logical sense. Until then, they will remain mysterious and cryptic.

Hiding under a boulder, the greatest prophet learned that God is unknowable.

Under two boulders

For the past four years, we have lived under two boulders: COVID and Oct. 7. Each of these humbling catastrophes has taught us to speak less boldly and less confidently. We need to discover a voice of uncertainty and humility.

Life in the modern world infused us with too much confidence. Technology, democracy, capitalism, and science all empowered us toward greater optimism and greater confidence. Our opinions were too overconfident, and COVID-19 dealt a crushing reminder about the limits of modern culture. It helped us replace our voice of confidence with a voice of vulnerability.

Life in Israel over the past 20 years has been even more empowering and confidence-infusing. During this period of dizzying and euphoric success, our population soared, our economy boomed, and we formed strategic peace alliances with numerous Arab neighbors. Dubbed a Start-Up Nation, we became the envy of the world. Israeli know-how and technology enabled us to desalinate seawater and made us naively assume we could build an impenetrable wall to protect us from our murderous neighbors.

Our confidence has now been shattered. The Arab world isn’t yet ready to embrace us, and the world at large is still not ready to allow us to live peacefully in our homeland.

Viewing our presence in Israel through a religious lens provides a further boost of confidence. Redemption is an essential tenet of Jewish belief. History has a predetermined endpoint, pivoted upon the restoration of our people to their ancient homeland. So much of the past 75 years in Israel appeared to sync with our prophetic expectations. It was obvious that Jewish history was veering toward its pre-programmed endpoint.

Absolutely certain we knew the arc and timelines of history, we spoke with confidence and conviction. Everything seemed to be humming along – until Oct 7.

Few words

In Ecclesiastes, Solomon writes: “Don’t speak impetuously and don’t be rash with your feelings because God inhabits heaven, and you live below on Earth. Therefore, your words should be few.” Over the past four years, heaven and the ways of God have seemed more distant than ever. Under these conditions, we must speak less, and when we do speak, we should voice our opinions with greater humility and less certainty.

Of course, faith outlasts any event on this Earth, as tragic and horrific as it may be. My revered mentor, Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein, stated that faith should be so sturdy that you are capable of being the last Jew to walk out of Auschwitz and still maintain your faith. Faith provides certainty and hope, especially during dark times.

However, just because we are faithful doesn’t mean we have all the answers. If anything, faith enables us to live under the weight of unanswerable questions. Faith allows us to embrace the unknown but not to assume that we know everything.

We must learn to better calibrate our voices between faith and uncertainty. We don’t have all the answers. We know the general trajectory of history but cannot guarantee every step of the process. More humility and less conviction. More modesty and less confidence.

After four years and two heavy boulders, our voice must be less presumptuous.

Hopefully, this chaotic four-year revolution will provide us all with a more measured and mature voice.

The writer is a rabbi at Yeshivat Har Etzion/Gush, a hesder yeshiva. He is an ordained rabbi and holds a BA in computer science from Yeshiva University, as well as an MA in English literature from the City University of New York.