Don’t forget Philip Johnson’s Nazi past

In 1932, as a rising star at the Museum of Modern Art, Johnson attended a Hitler Youth rally at Potsdam.

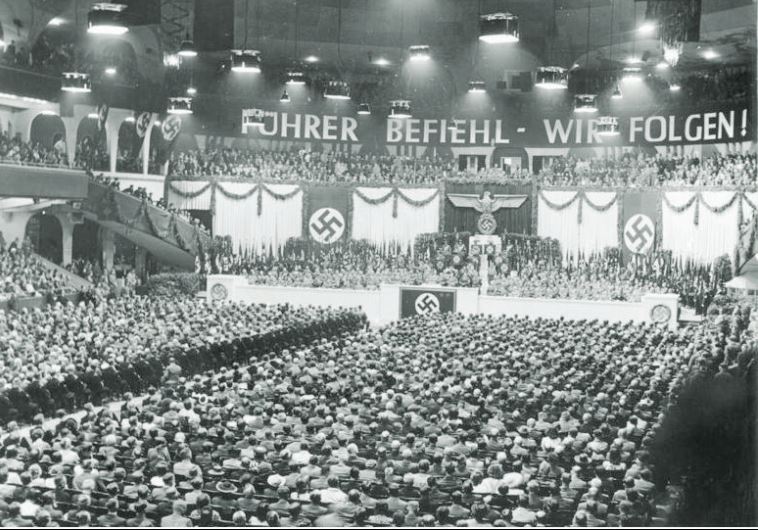

Germans take part in a mass Nazi rally in the Berlin Sports Palace in June 1943(photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Germans take part in a mass Nazi rally in the Berlin Sports Palace in June 1943(photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)