The relationship between the human mind and body has been a subject that has challenged great thinkers for millennia, including the philosophers Aristotle and Descartes. The answer, however, appears to reside in the very structure of the brain.

Researchers said on Wednesday they have discovered that parts of the brain region called the motor cortex that govern body movement are connected with a network involved in thinking, planning, mental arousal, pain, and control of internal organs, as well as functions such as blood pressure and heart rate.

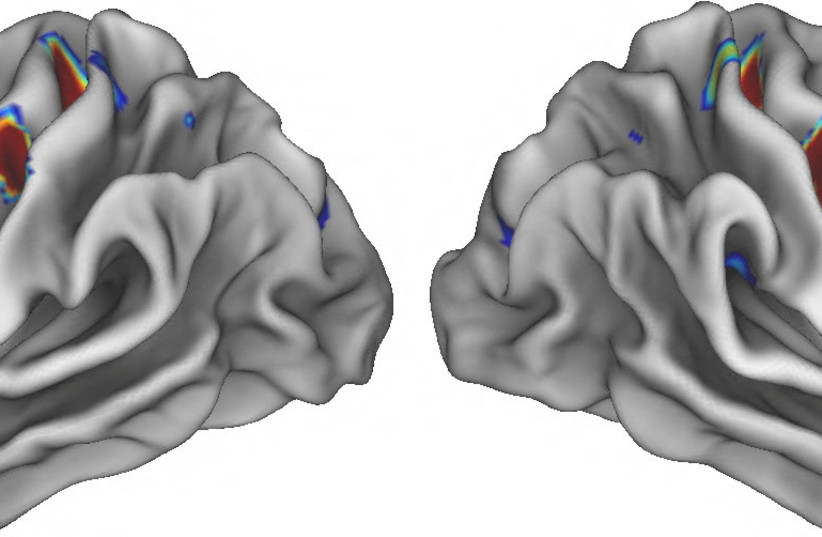

They identified a previously unknown system within the motor cortex manifested in multiple nodes that are located in between areas of the brain already known to be responsible for movement of specific body parts - hands, feet and face - and are engaged when many different body movements are performed together.

The researchers called this system the somato-cognitive action network, or SCAN, and documented its connections to brain regions known to help set goals and plan actions.

This network also was found to correspond with brain regions that, as shown in studies involving monkeys, are connected to internal organs including the stomach and adrenal glands, allowing these organs to change activity levels in anticipation of performing a certain action. That may explain physical responses like sweating or increased heart rate caused by merely pondering a difficult future task, they said.

The motor cortex is a part of the brain's outermost layer, the cerebral cortex.

"Basically, we now have shown that the human motor system is not unitary. Instead, we believe there are two separate systems that control movement," said radiology professor Evan Gordon of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, lead author of the study published in the journal Nature.

"One is for isolated movement of your hands, feet and face. This system is important, for example, for writing or speaking -movements that need to involve only the one body part. A second system, the SCAN, is more important for integrated, whole body movements, and is more connected to high-level planning regions of your brain," Gordon said.

The findings detail the brain's mind-body nexus.

"Modern neuroscience does not include any kind of mind-body dualism. It's not compatible with being a serious neuroscientist nowadays. I'm not a philosopher, but one succinct statement I like is saying, 'The mind is what the brain does.' The sum of the bio-computational functions of the brain makes up 'the mind,'" said study senior author Nico Dosenbach, a neurology professor at Washington University School of Medicine.

"Since this system, the SCAN, seems to integrate abstract plans-thoughts-motivations with actual movements and physiology, it provides additional neuroanatomical explanation for why 'the body' and 'the mind' aren't separate or separable," Dosenbach added.

The researchers set out to use modern brain-imaging techniques to test an influential map established nine decades ago by neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield of the brain areas controlling movement. Their findings showed that Penfield's map, constrained by the technologies of his time, needed revisions.

The SCAN was identified using precision imaging in seven adults to examine the brain's organizational features, then verified in larger datasets that when combined spanned thousands of adults. Further imaging identified the SCAN circuit in an 11-month-old and a 9-year-old, while finding it had not yet formed in a newborn. Those observations were validated in larger datasets of hundreds of newborns and thousands of 9-year-olds.

The research underscored how there is more to learn about the human brain.

"Actually, the purpose of the brain is highly debated," Gordon said. "Some neuroscientists think of the brain as an organ intended primarily to perceive and interpret the world around us. Others think of it as an organ designed to produce the best 'outputs' - usually a physical action - to optimize survivability and evolutionary fitness for any given situation."

"Probably both are correct," Gordon added. "The SCAN fits most cleanly with the latter interpretation: it integrates goals and planning with whole-body actions."