On June 11, 1967, after six days of fighting on three different fronts, Israelis awoke as if from a dream.

Gone was the immediate threat of destruction so many felt in the tense weeks leading up to the war. Cast off was the inability to touch the ancient, creviced stones of the Western Wall. A thing of the past was the Syrian shelling from the Golan Heights.

For more stories released for the 55th anniversary of the Six Day War, click here.

In the span of just 132 hours, a dream of centuries had been realized: Jews were in control of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem’s Old City, they could pray at Rachel’s Tomb on the road to Bethlehem, visit the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. The words of the prayer recited by Jews thrice daily for millennia – “May our eyes behold Your return to Zion in mercy” – seemed to have been fulfilled.

And not only in Jerusalem. Overnight the country had physically grown by more than three times. Israel’s suffocating border lines were extended. The country finally had some strategic space.

In that euphoria, in that dream-like state, little thought was given to what was next. It’s as if thinking about the next steps would be to prematurely end the dream, to wake up to reality.

And who wants to rush a dream?

Israel did not go into the Six Day War intending to conquer the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, east Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria and the Golan Heights. As such, it had no plans before the war of what to do if that would be the final result. No one foresaw that conclusion, and the fact that Israel ended up holding all of those territories was to a large extent a result of decisions made in the heat of battle.

Nor, however, did it formulate a strategic plan or vision when the guns fell silent. From day one it improvised, waiting to see what the next day would bring, how things would develop, what – if any – opportunities would arise. And, to no small degree, that has been the situation ever since.

The government at the time was divided as to what to do with the territories, a division that remains to this day. As such, it was either impossible to agree on policy, or decisions were just put off.

But, to paraphrase fabled baseball legend Yogi Berra, don’t be surprised if when you wake up in the morning, and you don’t know where you are going, that you are not going to get there. When it comes to what it had in mind for Judea and Samaria, Israel did not clearly define goals that it could then pursue. You can’t achieve what you can’t define, and Israel – from the first day after the Six Day War – never defined clearly what solution for those areas it had in mind. The country simply could not agree.

The same, however, is not true about the Sinai and the Golan Heights.

Udi Dekel, a former head of the IDF’s Planning Directorate and a former chief negotiator with the Palestinians who now currently heads the Institute for National Security Studies’ programs on the Palestinians, said in an interview that at a government meeting within days of the war’s end, then-prime minister Levi Eshkol posed the question about what to do with the territories won in the war. “Most of the ministers said that regarding the Golan and the Sinai, the idea was territory for peace, and that in return for peace agreements, Israel would be willing to return territory.”

“Most of the ministers said that regarding the Golan and the Sinai, the idea was territory for peace, and that in return for peace agreements, Israel would be willing to return territory.”

Udi Dekel

In fact, a resolution to this effect passed the cabinet by a single vote, 10-9.

Likewise, the government made a quick decision that Jerusalem would remain a united city under Israeli sovereignty. It failed, however, to define in any meaningful way what plans it had for Judea and Samaria and the Palestinians who lived there.

Some of the ministers, those who fought in the War of Independence in 1948-1949, and who felt that Israel missed a historic opportunity at that time to take control of Jerusalem’s Old City and its biblical heartland, wanted to immediately annex the West Bank. For instance, Dekel said that then-labor minister Yigal Allon was in favor of immediate annexation. Allon felt that with the Arab world and the international community in shock by the dimensions of the victory, Israel should act immediately and not wait.

Others, however, were opposed, saying it was too soon to make such a fateful decision, and that it would be best to “wait and see” in the hope that some kind of agreement could be reached with the Jordanians. They were supported outside the government by no less a personality than former prime minister David Ben-Gurion, who warned against annexation because of a concern about the demographics of incorporating into Israel some hundreds of thousands of Arabs who now came under its control.

A decision was made to accept the decision put forward by then-defense minister Moshe Dayan to extend military rule over the territories that were termed disputed, and then to “wait and see with time what it is possible to do with them.” The country is still waiting.

What is interesting is that at the time, according to Dekel, when considering the final dispensation of Judea and Samaria, “no one thought in terms of the Palestinians, but rather what to do with regard to Jordan,” which had occupied the West Bank until then.

Jordan, at that time, was seen as the address for any future arrangement regarding the West Bank.

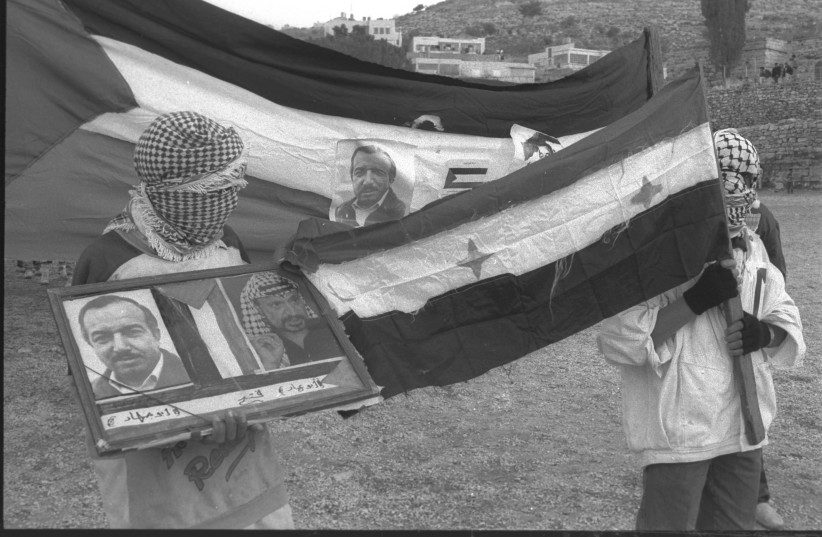

Ironically, said Michael Oren, Israel’s former ambassador and the author of a book on the war titled Six Days of War: June 1967 and the Making of the Modern Middle East, “The Palestinians were in many ways the big victors of 1967. Before 1967 no one talked about the Palestinians, no one knew who they were. If you read Life magazine, and you saw a reference to Palestinians, it was to Jews in Palestine before 1948. Palestinians were Jews and Arabs were Arabs. The war in 1967 put the Palestinians on the map. For all sorts of reasons, the Palestinians stopped looking at [Egyptian president Gamal Abdel] Nasser and Arab leaders to bring about their liberation. Note that only seven years later, [PLO chief Yasser] Arafat gets a standing ovation at the UN.”

This process culminated in 1988, when Jordan’s King Hussein removed his hand completely from the West Bank, with the exception of guardianship over Muslim and Christian holy sites in Jerusalem. At that time he recognized the PLO as the “sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people.”

Land for peace

OREN SAID there were two main reasons why the same territory-for-peace formula that the government accepted regarding the Golan Heights and Sinai was not extended to Judea and Samaria. One, because the border was too narrow; it was indefensible. And secondly because of the religious, historical and emotional ties to the Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael).

In the immediate aftermath of the war, Oren said, the predominant feeling was that “we would get a peace agreement with Jordan, and as part of that agreement we would establish an autonomous Palestinian area in Judea and Samaria.” The agreement that emerged on the Temple Mount, whereby Israel would have security control, there would be a Jordanian trusteeship through the Wakf Islamic religious trust and some kind of Palestinian autonomy at the site there was a model for what Israel had in mind for the rest of Judea and Samaria, he said.

Oren said that the government sent emissaries to some 180 prominent Palestinians in the West Bank to feel out the idea and see whether they would be willing to accept autonomy.

“Almost all said no, and the reason they gave was that if they did, a guy named Yasser Arafat would kill them,” he said.

Dekel, in an INSS publication put out five years ago about the Six Day War, wrote that the “euphoria following the victory in the Six Day War was combined with perplexity. This was reflected in the lack of thinking about the possible implications of the war’s results, whether expressed in government deliberations or in statements by Israeli leaders.

“The political leadership did not succeed in translating and promoting the impressive military win into advancing peace agreements, and the IDF was given the main role of administering the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (‘the territories’), without examining in-depth the significance and the consequences of the encounter between an army and the Palestinians under occupation. The statements of prime minister Levi Eshkol reveal the euphoria following the capture of parts of the Land of Israel that had been cut off from the state since 1948 and, in parallel, the desire not to close the door on the chances of peace by creating permanent facts on the ground.”

From the very start, there was a conflict in the government between those excited by the return to the nation’s biblical heartland and those concerned about the long-term implications of absorbing so many more Arabs.

“The determined opposition of some of the ministers to returning any territory on the one hand and the desire among the others to avoid having to rule over one and half million Palestinians on the other hand, placed the government in a state of disagreement regarding the content of the territorial proposal to be submitted to Jordan,” Dekel wrote. In the end, it chose “not to make any decisions regarding its future policy” and decided, as an interim stage, to set up a military administration until a final decision was made regarding the future status of the West Bank.

Eshkol, in a moving speech to the cabinet on June 11, said, “Today it is possible to say, we won the war, and now start the concerns over peace, permanent peace. We should only have the resourcefulness, wisdom and understanding to know how to manage all this property, and I do not mean only the real estate. With all the success on the battlefield, there is a need for much wisdom and understanding, because problems of peace are also accompanied by many difficult questions.”

Dekel quoted Aharon Yariv, who was the head of Military Intelligence at the time, saying there was “essentially no strategic plan for the day after the war.” In other words, there were no answers to the difficult questions about peace.

“From that time until today, the name of the game has been to buy time,” Dekel said. “It is not clear for what purpose, but to buy time, so we don’t have to make the tough decisions, so we kick the issue down the road.”

In the meantime, however, things change: conditions change, the situation on the ground changes, the region changes. One might wait, but nothing stands still.

On the day after the Six Day War, Israel lacked a grand strategy for what to do with the lands that fell under its control. It lacked the determination to decide what it really wanted, and then pursue it. Not everything is in its hands, and there is another side that has a say, and much depends on it.

But “depends” is not a policy, and waiting is not a winning long-term strategy. Going back to those euphoric days immediately after the Six Day War, Israel has never clearly defined or articulated its ultimate vision for Judea and Samaria. It never set its goal line. And if a goal line is not set, it can never be crossed. ■