It has long been known that the Mediterranean Sea basin during the Late Bronze Age was a pretty busy place, characterized by complex relations amongst kingdoms and diplomatic connections outside of the region, making it a busy marine corridor for trade and gifts amongst the elite and from one ruler or king to another.

Research by Hebrew University professors on lead ingots and stone anchors which were found among shipwrecked cargo off the coast of Israel has now revealed previously unknown elaborate trade links among distant countries. The analysis of these ancient finds sheds light on commercial and diplomatic life in the areas from 3,200 years ago.

Especially during the 13th and 14th centuries BCE there was a very elaborate trade system and formal levels of exchanges and gift-giving between the palatial centers all around the Mediterranean, from Babylon, Greece, Anatolia and other areas along the basin. The terms and conditions of these exchanges were set out in ancient archives found in Ugarit, an ancient port city and economic center in what is today northern Syria.

“These spelled out how these interactions would go on,” said Hebrew University archaeology professor Naama Yahalom-Mack who collaborated with Professor Yigal Erel at HU’s Institute of Earth Sciences to determine the source of four lead ingots among a shipwreck’s cargo found near the port of Caesarea several decades ago. “But what we know less of is the smaller traders who were taking advantage of this informal trade when there was a really high demand for raw material and prestigious objects. They had smaller boats and were not sent out by a formal king or kingdom.”

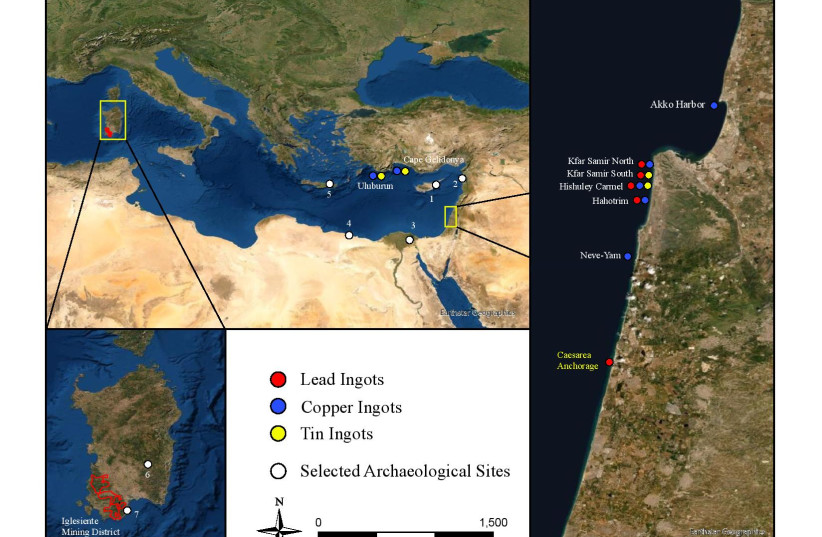

By studying the source of the lead and comparing their findings to other archeological artifacts from across the Mediterranean Sea, the researchers were able to prove that the ingots were made of lead mined in the central Mediterranean island of Sardinia. Further, the ingots were incised with Cypro-Minoan markings which, though undeciphered to this day, are known to have been in use in Cyprus during the Late Bronze Age. Accordingly, the researchers concluded that there were vast commercial ties between the two populations with the purpose of transporting raw material.

“During this time one of the main products being traded was metal, especially copper which was produced by the ton in Cyprus, an island very rich in copper,” Yahalom-Mack said.

But the mystery remained as to how involved the Cypriots were in the metal trade themselves, or if they were simply producers, and passive in its trade.

Using analysis involving lead isotopes which produce a fingerprint of sorts, the researchers compared analysis of the lead ingots from Caesarea to analysis previously conducted on other artifacts made from lead. The source of lead with the best match was in the region in the southwest of the island of Sardinia along the Iglesient coastline.

“We realized that the ingots from along the Israelis coast and the other artifacts all came from the same source, which means this was not just a one-time journey to bring these ingots to the coast, but rather a continuous and elaborate trade system which was probably initiated by the Cypriots,” she said.

Further, Yahalom-Mack said, as the markings on the ingots pointed them toward Cyprus, the information about the rest of the lead objects they used in their analysis which came from the same sources, enabled them to both date when the exchange of the ingots was to take place and also helped them to reconstruct how elaborate the trade was at that time—involving not only Cyprus and Sardinian, but rather also Egypt and the entire Levantine coast.

Yahalom-Mack said their analysis teaches about the active role that the Cypriots had in trade during the same era, and how far they were willing to go—given that Cyprus and Sardinia are located more than 2,500 km (1550 miles) from one another-- in order to import lead, used to create luxury goods at the end of the era.

“We think that along with lead, they also imported tin — a sought-after metal in Cyprus and the surrounding area for making bronze. These three metals — copper, lead, and tin — were sold to port cities along the coastlines, including the shores of today's Israel," she added.

In order to cast elaborate bronze objects popular at the time, tin was needed to add to the copper, Yahalom-Mack explained. Apparently, she said, they set out to find lead, and for some unknown reason instead of sailing to Anatolia which is just across from Cyprus and has lead sources, they sailed to Sardinia in the western Mediterranean.

The findings were published in the Journal of Archaeological Science Reports’ February edition and was conducted in collaboration with Prof. Assaf Yasur-Landau and Dr. Ehud Galili at the University of Haifa’s Institute for Maritime Studies.