The analysis of artifacts is ordinarily conducted in laboratories, which makes the scientific examination of art in ancient tombs very rare. Now, archaeologists have brought sophisticated technology to the tombs and are changing our thinking on how pharaonic wall art was made.

The material study of ancient Egyptian paintings began with the advent of Egyptology during the 19th century. By the 1930s, a lot had already been sampled and described. The limited palette for example has been analyzed from actual painted surfaces but also from pigments and painting tools retrieved on site.

Portable chemical imaging technology can reveal hidden details in ancient Egyptian paintings, according to a study by Philippe Martinez of Sorbonne University Martinez and colleagues in Paris. in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Liège in Belgium.

Their study was just published in the journal PLOS ONE under the title “Hidden mysteries in ancient Egyptian paintings from the Theban Necropolis observed by in-situ XRF mapping.”

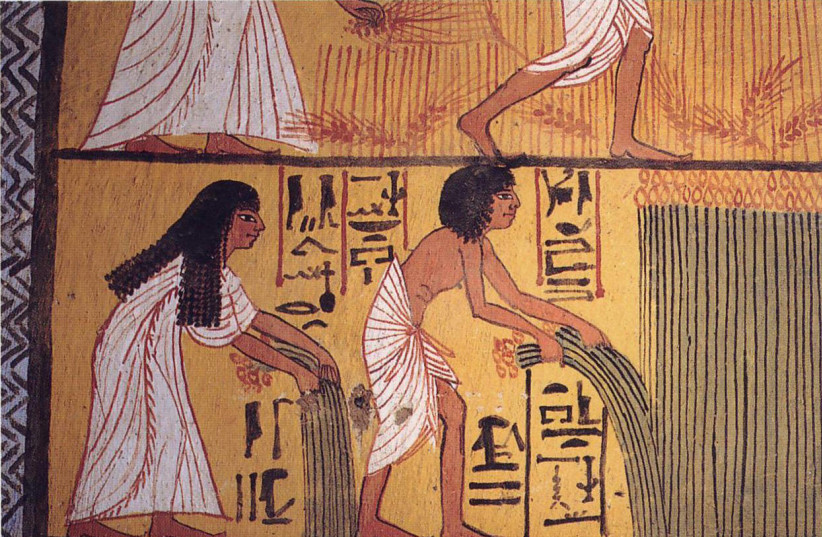

Two paintings were analyzed in detail, both located in tomb chapels in the Theban Necropolis near the River Nile, dating to the time of the Pharoah Ramses II. The identity of Pharaoh in the Moses story has been much debated, but many scholars are inclined to accept that Exodus has King Ramses II in mind.

Studying the paintings

Most of these studies took place in museums while the painted surfaces, preserved in funerary chapels and temples, remained somewhat estranged from this primary physical understanding. The artistic process has been also reconstructed, mainly from the information presented by unfinished monuments, showing surfaces at different stages of completion. A lot of this modern and theoretical reconstruction is, however, based on the usual archaeological guessing game that aims at filling the remaining blanks.

On the first painting, researchers were able to identify alterations made to the position of a figure’s arm, though the reason for this relatively small change is uncertain. On the second painting, analysis uncovered numerous adjustments to the crown and other royal items depicted on a portrait of Ramses II, a series of changes that most likely relate to some change in symbolic meaning over time.

Such artworks are commonly thought to be the result of highly formalized workflows that produced skilled works of art, but most studies of these paintings and the process that created them take place in museums or laboratories. In this study, use portable devices to perform chemical imaging on paintings in their original context, allowing for analysis of paint composition and layering and for the identification of alterations made to ancient paintings.

Such alterations to paintings are thought to be rare among such art, but the researchers suggest that these discoveries call for further investigation. Many uncertainties remain about the reasoning and the timing behind the alterations observed, some of which might be resolved by future analysis. This study also serves to prove the utility of portable chemical imaging technology for studying ancient paintings in-situ.

The authors added that “these discoveries clearly call for a systematized and closer inspection of paintings in Egypt using physicochemical characterization.”