Hundreds of thousands of years ago, early humans living in the area of the modern State of Israel were aware that what animals ate influenced the taste of their meat of the quality of their hide, and chose their hunting grounds based of their culinary preferences and needs for supplies, new research based on remains uncovered at the site of Qesem Cave has suggested.

A group of Israeli and Spanish experts analyzed hundreds of animal remains uncovered in the cave, especially teeth, and understood that different areas of the site were devoted to different activities – such as butchering, extracting bone marrow or treating the skins. In addition, they were surprised to find out that the animals processed in these areas, despite belonging to the same species, were characterized by different diets, according to Tel Aviv University Professor of Prehistoric Archaeology Ran Barkai.

“Qesem Cave was visited by early humans beginning around 400,000 years ago and up to 200,000 years ago,” he said. “It was a very interesting period in terms of human cultural and biological evolution because we are talking about a human type that came right after Homo Erectus, the common ancestor of Sapiens and Neanderthal, and just before them.

“This period was characterized by many technological innovations, including the beginning of the use of fire,” he said.

Located in the Samaria Hills, the cave remained sealed and not accessed until the year 2000 when it was uncovered by chance. It, therefore, offers a range of very well-preserved artifacts and traces of Paleolithic life distributed through 11 meters of archaeological layers.

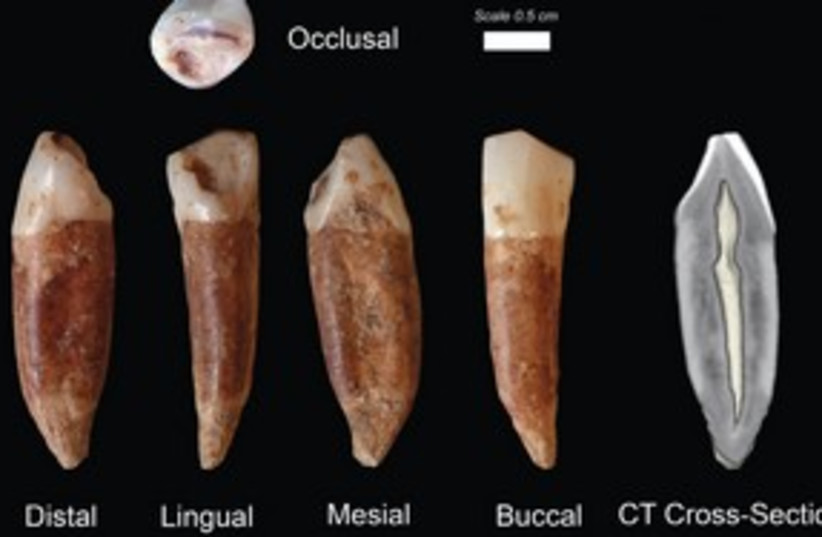

Thousands of animal remains were found, mostly of fallow deer and horses, including many skulls and teeth.

“Teeth are especially interesting because based on their wear it is possible to understand what kind of food the animal consumed and, in some cases, also during which season of the year it was hunted,” Barkai said.

THE CAVE was not permanently occupied but was still very organized – and season after season, for years if not tens of thousands of years, its residents maintained the same organization.

“There were several fireplaces. Some areas were devoted to manufacturing stone tools, some areas to processing animal hides, others to breaking animal bones to extract bone marrow and so on,” Barkai said.

The researchers found out that in different areas of the caves, the animals were hunted in different seasons, therefore the cave was used for long periods of the year, at least several months long.

“What was totally unexpected was that animals brought to specific areas of the cave had a specific diet,” Barkai noted. “For example, we discovered that fallow deer who ate only leaves were brought to the central fireplace of the cave. At the same time, the fallow deer found where hides were processed also ate branches and grass. This pattern is recognizable in different areas of the site.”

According to Barkai, animals who presented similar diets were hunted in the same hunting grounds.

“Our interpretation is that those early humans chose where to go hunting based on the specific benefit that the animals from there could offer them, including in terms of food preferences,” he noted. “In other words, the food that the animals ate influenced the resources humans wanted to extract from them: They knew that meat from a certain area where deer ate leaves would have a certain kind of flavor, while deer which consumed other forms of vegetation would present different qualities.

“Their knowledge of the environment where they lived was much more sophisticated than we envisioned,” he said.

For the future, the researchers are working to understand more about how the dietary practices of animals affected their potential in terms of what early humans were looking for in them.

“We would like to uncover more about how the food fallow deer and horses were eating influenced their qualities and how humans considered them.”