What was an ancient kingdom supposed to look like in order to qualify as wealthy and powerful?

An Israeli scholar argues that for too long, the answer to this question has been suffering from an inherent, sometimes even unconscious bias: the need to find evidence for palaces, large cities and all those elements that in a Western world mindset would suggest prosperity and influence.

“The biblical story is about nomads,” Tel Aviv University Prof. Erez Ben-Yosef said. “Almost everybody agrees that ancient Israel emerged from a nomadic society, and the same is true for the neighboring kingdoms – the Moabites, the Edomites, the Ammonites – which were established by coalitions of nomadic tribes.”

As Ben-Yosef noted in a paper recently published in the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology, up until now, the consensus among scholars has been that before a society became sedentary, it could not be considered complex or evolved. For this reason, many have dismissed the notion that ancient Israel could be as powerful as described in the Bible.

However, in order to understand the Israel of King David and King Solomon, a new approach is required, one that leaves behind the need for remains of magnificent buildings but is able to ask the right questions and put archaeological and historical records in the right perspective.

“The problem is that when we think about nomads we immediately think about modern Bedouin and we find ourselves stuck in a certain mental box,” Ben-Yosef noted. “It is time to leave this box.”

According to the scholar, the mistake is understandable.

“Normally, archaeology does not offer us the possibility to study nomadic societies and their material culture, so we based our conclusion off assumptions,” he said.

Tents in fact do not leave remains around for millennia.

“At the same time, archaeologists have wanted to be important players in the discussion about the historicity of the Bible and have claimed that they could see more than they could,” Ben-Yosef argued. “However, now we have very strong evidence that this approach was wrong and that what we thought about nomads in the ancient Land of Israel was wrong.”

FOR THE PAST eight years, the archaeologist has been excavating at Timna, where he is currently director of excavation.

Located in the Arava in Sourthern Israel, the site was traditionally associated with King Solomon and his kingdom dating back some 3,000 years – until some archaeological remains uncovered at the end of the 1960s suggested that its ancient copper mines were operated by the Egyptian Empire two centuries earlier.

However, in recent years, radio-carbon dating of organic material found at Timna proved that the most intense activity of the site happened around 1,000 BCE, the time of David and Solomon.

According to Ben-Yosef, the site was part of the nomadic Edomite Kingdom, but might have been under nomadic Israel’s control as the Bible suggests. Crucially, Timna presents ample evidence that societies did not need to be sedentary or to leave grand palaces behind to be rich and influential.

“In the past there was a consensus that only an empire could be responsible for such a huge operation, which required thousands of workers, but at the time when the mines were active, there was no empire in the region, but only these tribes and coalition of tribes which worked as kingdoms, without building cities,” he said.

Only the fact that this specific nomadic polity engaged in copper production allowed the evidence of its complexity to survive: The mining activity left tons of copper slag in the site, and since its occupation lasted a long time, other finds were also unearthed, including pottery and organic remains that were preserved thanks to the dry climate.

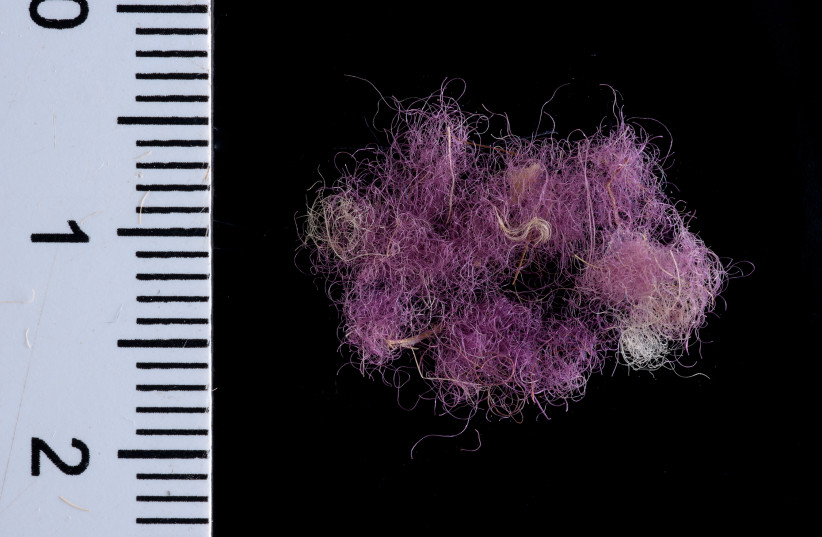

The remains include refined foods such as almonds and fish and even fabrics dyed with the purple argaman, the most expensive pigment of the time and a status symbol of the elites in ancient societies in southern Levant.

So what did the contemporary kingdoms of David and Solomon look like?

According to Ben-Yosef, a significant part of the population was still tent-dwelling.

“As it was common at the time, it was a mixed society with some people living in tents and others in buildings,” he said. “As the biblical author tells us, with time, more people settled but many continued to live in tents all the way to the destruction of the First Temple.”

In addition, at the time, also ruling over or controlling another population did not depend upon fortresses built to supervise them, could be based on tax collection or agreements, as it is also described in the Bible, for example, regarding the relation between Israel and Edom.

“The biblical text is complex and it does contain some biases and exaggerations, but I believe it contains much more truth than many assume,” Ben-Yosef said.

“We cannot use archaeology in the way it has been used until today to study the historicity of the Bible, we need to acknowledge the reality,” he concluded. “We cannot just continue to look for walls, our rules need to change.”

For more information, go to https://telaviv.academia.edu/ErezBenYosef/Papers.