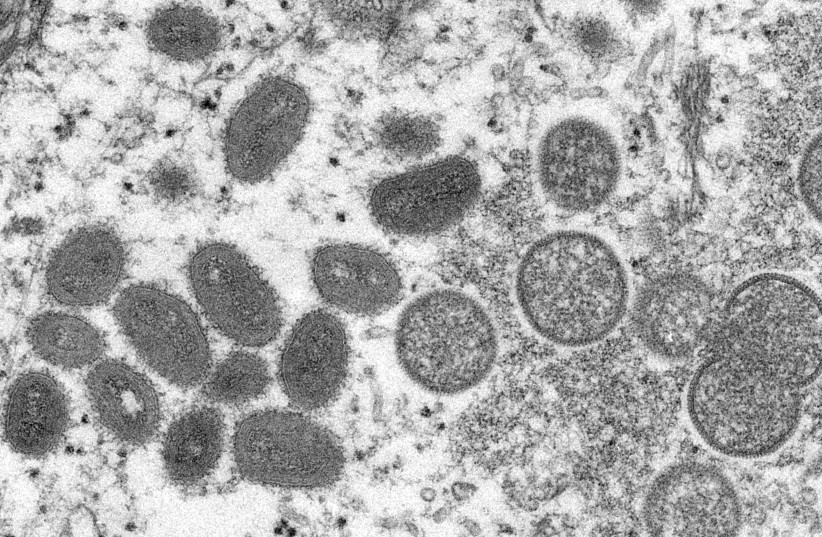

An unusual spread of the virus known as monkeypox has generated a fair amount of panic in recent days, as over 100 cases have been found across the globe – namely in the US, Europe, and the Middle East. It is easy to understand the panic: after all, over two years and multiple variants of the COVID-19 pandemic later, everyone is more cautious than they were before.

But scientists and health experts have overwhelmingly said that while it is good to be cautious and alert, there is no need to panic and that the situation now is in no way similar to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic back in early 2020.

In order to spread, monkeypox requires prolonged close contact with the infected individual, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has stated, saying that “respiratory droplets generally cannot travel more than a few feet, so prolonged face-to-face contact is required.”

According to the CDC, other human-to-human methods of transmission include “direct contact with body fluids or lesion material, and indirect contact with lesion material, such as through contaminated clothing or linens.”

Monkeypox is a viral infection, typically found in central and western Africa, although there have been cases of isolated infections in the past in other areas of the world. Of the two strains of monkeypox, health officials believe that the current infections are being caused by the spread of the milder, West African strain as opposed to the more severe Central African one.

Even if monkeypox does become more prevalent over the coming weeks or months, there is still little cause for panic. While it can cause death if left untreated (like most diseases), the smallpox vaccine has shown a success rate of 85% when it comes to stemming infection, and an antiviral drug known as tecovirimat is used specifically to treat a variety of orthopoxviruses, including monkeypox.

Furthermore, the cases identified in Europe are of the more mild strain, with a proven fatality rate of less than 1%. The more severe strain, which has a fatality rate of 10%, has not been proven to be spreading at this time. Therefore, even if monkeypox does continue to spread, and even in the unlikely scenario of it reaching epidemic-level proportions, there is little to worry about at this time.

But besides monkeypox, what other viruses have the possibility of progressing from rare, isolated outbreaks to widespread ones with a possibility of becoming epidemics in unusual places?

Ebola Virus Disease

Ebola Virus is a rare but deadly viral disease first discovered in 1976 in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in the area that is now South Sudan. Since its discovery, the majority of outbreaks and cases that have been recorded have occurred on the African continent. Between 2014-2016, however, an outbreak of the Ebola virus that had started in the West African Republic of Guinea spread across borders and quickly became classified as a global epidemic, ultimately taking some 11,300 lives.

The symptoms of Ebola can be confused with typical influenza symptoms at the start of the infection, with weakness, fever, headache, a sore throat and muscle pain being common identifiers.

As the virus progresses, it causes internal bleeding as well as bleeding from the eyes, ears and nose, and inside the digestive tract.

During the 2014-2016 epidemic, a two-year vaccine trial was conducted in Guinea, with the results finding that the vaccine dubbed rVSV-ZEBOV had been effective. Of 6,000 people vaccinated with it, none contracted Ebola after being exposed to it ten days later. In the unvaccinated group, 23 people contracted the virus.

In addition to protecting vaccinated people, the vaccine has proven to protect unvaccinated people indirectly, through herd immunity. However, research is still lacking when it comes to understanding how long the vaccine is effective, and whether it will be effective in stopping other strains of the virus.

The most recent recorded Ebola outbreak was just over a year ago, in February 2021. However, due to the resources and experience gained from the 2014-2016 epidemic, combined with experience from fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, it was successfully contained before it could again become an epidemic.

According to World Health Organization reports, there is a possibility that Ebola virus outbreaks will become more common in the near future, due to deforestation. The reports suggest that due to the clearing of forests, various types of bats will be removed from their natural habitats, moving closer to human populations and increasing the risk of cross-species contamination.

Zika fever

Zika fever is a mosquito-borne viral disease, first discovered in monkeys in Uganda in 1947, and later in humans in Uganda and Tanzania in 1952. It is transmitted by the bite of an infected Aedes mosquito – the same mosquito that transmits yellow fever and other diseases – usually found in tropical and subtropical regions.

The symptoms of Zika tend to be mild and usually last from several days to a week. Both hospitalization and death rates are low, and the most common symptoms include fever, a rash, muscle pain and conjunctivitis.

However, despite the mild symptoms, the disease still poses a risk, particularly when it infects a pregnant woman. The disease can spread to her unborn baby, causing severe birth defects and brain injury.

The most recent Zika virus epidemic occurred between 2015-2016 when it spread across the American continent – encompassing North America, South America and Central America – as well as the Caribbean. At the time, it was estimated that 1.5 million people were infected in Brazil alone, causing 3,500 instances of birth defects.

Similar to the COVID-19 pandemic, albeit on a smaller scale, a number of countries issued travel warnings and there were concerns over the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Summer Olympics sparking widespread transmission. However, these concerns did not materialize, and by November 2016, the WHO declared that Zika was no longer a global emergency.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

SARS is a viral respiratory infectious disease, originating in China in 2002 and caused by a coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-1. The virus was simply referred to as SARS-CoV until December 2020, when a new strain was identified, ultimately creating the COVID-19 pandemic.

The first known outbreak of the disease occurred in China in November 2002 and quickly spread across the Asian continent and beyond, causing the 2002-2004 SARS epidemic.

The symptoms of the original coronavirus disease share strong similarities with the strain responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The milder symptoms included high fever, headache, muscle pain, loss of appetite and fatigue. However, when the infection reached the stage in which it affects the respiratory system, it caused severe breathing difficulties and a lack of oxygen in the blood.

While SARS caused a relatively low number of infections in comparison to the other epidemics listed, it had a mortality rate of 11%, causing 775 deaths in just eight months.

Although the virus disappeared almost as fast as it appeared, with not a single case of it being reported since late 2004, there is no guarantee that it won’t reappear in the future. And indeed, as seen by the 525 million COVID-19 cases recorded worldwide to date, even if the original strain of the virus is no longer a risk, variants may emerge.