Being a “fast talker” has a negative connotation – trying to persuade or influence others using deceptive, tricky, fluent talk. But in the elderly, talking fast is a good thing, showing that one is probably not on the path to cognitive decline and dementia.

Word-finding difficulty (WFD) is a common cognitive complaint among the elderly, showing both in natural speech and in controlled laboratory tests. Various theories of cognitive aging have been made about this, and understanding its underlying mechanisms could help clarify whether it has diagnostic value for neurodegenerative disease.

A new study by the University of Toronto and the city’s Baycrest Rotman Research Institute suggests that talking speed is a more important indicator of brain health than difficulty finding words, which appears to be a normal part of aging. This is one of the first studies to look at both differences in natural speech and brain health among healthy adults.

“Our results show that changes in general talking speed may reflect changes in the brain,” noted lead author Dr. Jed Meltzer at Baycrest, a global leader in aging and brain health. “This suggests that talking speed should be tested as part of standard cognitive assessments to help clinicians detect cognitive decline faster and help older adults support their brain health as they age.”

They published their study in the journal Aging Neuropsychology and Cognition ITALICS under the title “Cognitive components of aging-related increase in word-finding difficulty.”

Participants undergo various tests

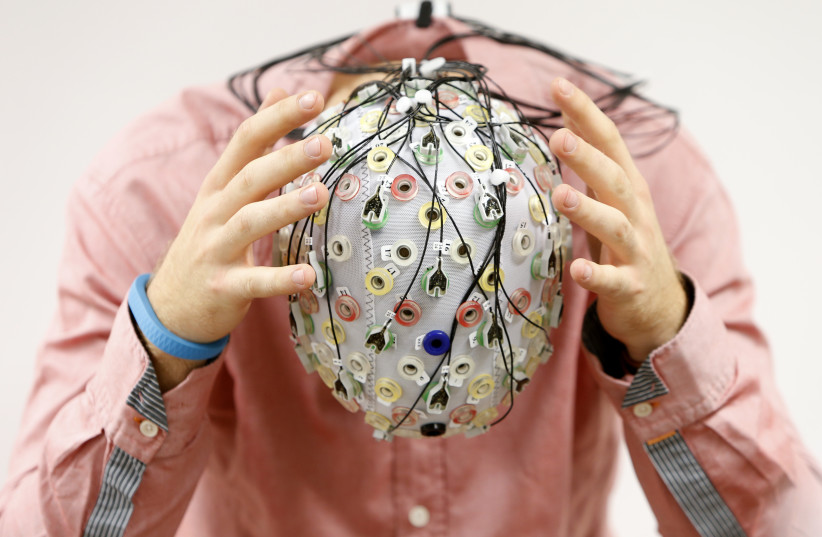

In this study, 125 healthy North American native English speakers aged 18 to 90 were recruited to complete three different assessments. The first was a picture-naming game in which they had to answer questions about pictures while ignoring distracting words they heard through headphones. For example, when looking at a picture of a mop, they might be asked, “Does it end in ‘p’?” while hearing the word “broom” as a distraction. In this way, the researchers were able to test the participant’s ability to recognize what the picture was and to recall its name.

Next, participants were recorded as they described two complex pictures for 60 seconds each. Their language performance was then analyzed using artificial intelligence-based software in partnership with Winterlight Labs. Among other things, researchers examined how fast each participant spoke and how much they paused. Then, the research participants completed standard tests to assess mental abilities that tend to decline with age and are linked to dementia risk – namely, executive function, the ability to manage conflicting information, stay focused, and avoid distractions.

As expected, many abilities declined with age, including word-finding speed. Surprisingly, although the ability to recognize a picture and recall its name both worsened with age, this was not associated with a decline in other mental abilities. The number and length of pauses participants took to find words were not linked to brain health. Instead, how fast participants were able to name pictures predicted how fast they spoke in general, and both were linked to executive function. In other words, it wasn’t pausing to find words that showed the strongest link to brain health but the speed of speech surrounding pauses.

Although many older adults are concerned about their need to pause to search for words, these results suggest this is a normal part of aging. On the other hand, slowing down normal speech, regardless of pausing, may be a more important indicator of changes to brain health.

In future studies, the research team could conduct the same tests with a group of participants over several years to examine whether speed speech is truly predictive of brain health for individuals as they age. In turn, these results could support the development of tools to detect cognitive decline as early as possible, allowing clinicians to prescribe interventions to help patients maintain or even improve their brain health as they age.