A new development in diabetes technology could change the lives of millions of people with insulin-dependent diabetes.

For more stories from The Media Line go to themedialine.org

On Tuesday, the Israeli company, Betalin Therapeutics, announced progress in creating a “micro pancreas.” The experimental therapy, which is still in the preclinical trial stage, could ultimately free insulin-dependent diabetes patients from their constant dependency on injected insulin.

“This can become a cornerstone for solving the burden for people with Type 1 diabetes,” said Prof. Peter Schwarz, a member of Betalin’s advisory board and president-elect of the International Diabetes Federation, in a video for the company. “We have an enormous chance to have an impact on the quality of life, on societal aspects, economic aspects, and medical aspects for those patients.”

Worldwide, roughly 8.5 million people suffer from Type 1 diabetes, formerly known as juvenile diabetes. Type 1 can strike children and adults alike and involves an autoimmune response in which the patient’s own immune system destroys the pancreas’ ability to produce insulin.

The difference between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes is distinct from the much more common Type 2 version, which affects over half a billion people worldwide.

Type 2 is a metabolic disorder in which the patient’s body cannot effectively use the insulin it produces. In Type 1 versions of the disease, the body produces little or no insulin.

Patients with Type 2 diabetes can become insulin-dependent over time if their pancreas is no longer able to produce enough insulin. This can occur due to the progressive nature of the disease where cells in the pancreas become exhausted or destroyed due to long-term high blood sugar levels. When oral medications, diet, and exercise are insufficient to maintain blood sugar levels, insulin therapy becomes necessary. This state of insulin dependence is also referred to as "insulin-requiring" Type 2 diabetes.

The use of insulin pumps

In wealthy countries, one of the most common therapies for insulin-dependent diabetes is an insulin pump. This pump continuously injects insulin through a device placed under the patient’s skin.

Most pump users test their blood multiple times daily to monitor their glucose levels, count carbohydrates, and consistently instruct the pump on how much insulin to deliver.

Because insulin pumps are expensive, they are not widely used in middle-income and poorer countries.

Even with a pump, however, the daily life of a person with insulin-dependent diabetes is complex.

“The main problem is the decreased quality of life. It [diabetes] manages their lives,” Betalin Chief Technology Officer and co-CEO Dr. Racheli Ofir told The Media Line.

One alternative to the insulin pump is an islet cell transplant. In this procedure, surgeons implant pancreatic cells from cadavers into patients. However, this treatment’s viability is limited due to a lack of donors and the varied quality of donated cells.

Researchers have also used stem cells to replace lost or damaged beta cells, but their small size and their difficulty in engraftment in the patient’s body are challenging.

“Even if you inject the perfect cells,” Ofir said, “the rates of success are not high,” because “cells are friendly creatures. They need to have an environment, they must have other cells next to them, and they need to adhere to something.”

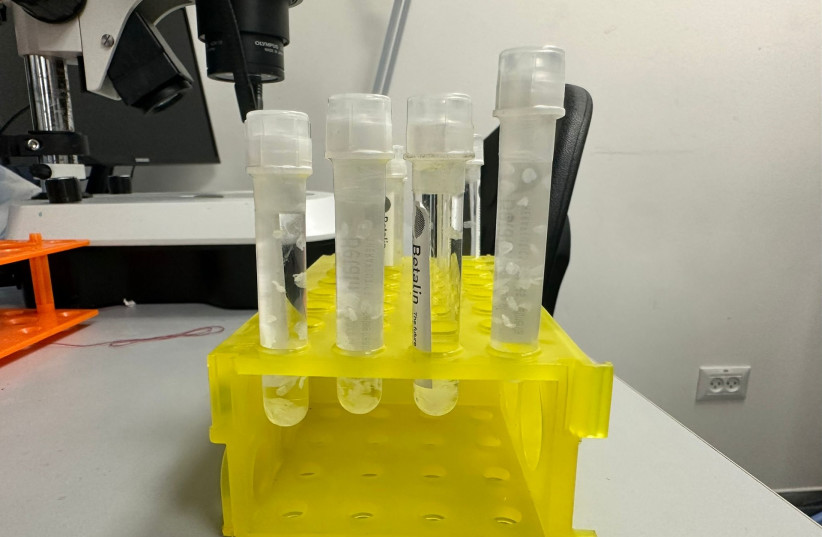

To address this, Betalin has developed a scaffold made of animal tissue that holds implanted beta cells in place and provides an environment that facilitates cell growth.

To build the scaffold, researchers take lung tissue from pigs. They mold the tissue, cut it, and then clean it, using a process of decellularization. This helps remove cell remnants from the tissue while retaining the functionality and integrity of the extracellular matrix.

This matrix is “the network, the home, for every cell,” Betalin lab manager Noam Mizrahi told The Media Line. “We have to ensure that we are not destroying and modifying it,” because the matrix is “the network we want to keep.” It will “let us seed the cells we need for the creation of a micro pancreas.”

Betalin has achieved successful preclinical results both in vitro and on animals such as mice and pigs, using islet cells. The next step is to achieve similar results with stem cells, which requires collaboration with other companies.

“We’re the house. If you take our home and then use somebody else’s stem cells or islets, together you create the micro pancreas,” Betalin CEO Dr. Moti Friedman explained.

As it continues to research and develop, the small Israeli startup is hopeful it will one day be able to offer a new diabetes therapy.

“It’s visionary, but it’s doable, and we are getting closer and closer to treating millions of diabetic patients. This is the goal, and we can see it coming,” said Ofir.

Hannah Levin is a student at Northwestern University and an intern in The Media Line’s Press and Policy Student Program.